“I said he’d peel to advantage, and so he would,” said Silas. “Did you see the right he landed to my jaw? Ah, he knows his way about, he does! Fair rattled my bone-box, I can tell you. And then you goes and lays him out before I’ve had time to do so much as draw his cork!”

“I’m thinking it was your own cork would have been drawn,” retorted Kennet, making his knots fast. “Take you his legs, man, and I’ll take his head. We’ll have him safe hidden in the carriage before he comes round.”

“I don’t deny he’s fast,” admitted Silas, helping to raise Mr Ravenscar from the ground. “But it goes against the grain with me to see as likely a bruiser knocked out by a foul, Mr Kennet, and that’s the truth!”

By the time they had borne Mr Ravenscar’s body to the waiting carriage, both men were somewhat out of breath, and extremely glad to be able to dump their burden on the back seat. Mr Ravenscar was no lightweight.

The carriage had left the Park, and was rumbling over the cobbled streets when Ravenscar stirred, and opened his eyes. He was conscious first of a swimming head that ached and throbbed, and next of his bonds. He made one convulsive attempt to free his hands.

“Ah, now, be easy!” said Kennet in his ear. “There’s no harm will come to you at all if you’re sensible, Mr Ravenscar.”

Mr Ravenscar was dizzy, and bewildered, but he knew that voice. He became still, rigid with anger: anger at Miss Grantham’s perfidy, anger at his own folly in allowing himself to be led into such a trap.

Another and deeper voice spoke in the darkness of the carriage. “You went down to a foul,” it said apologetically. “That weren’t none of my doing, for milling a cove down from behind is what I don’t hold with, and never did, “specially a cove as stands up as well as you do, sir, and shows such a handy bunch of fives. But you hadn’t ought to have gone a-persecuting of Miss Deb, when all’s said.”

Mr Ravenscar did not recognize this voice, but the language informed him that he was in the company of a bruiser. Hi closed his eyes, trying to overcome his dizziness, and to collect his wits.

By the time the carriage drew up outside Lady Bellingham’s house, it was dark enough to enable the conspirators to smuggle their prisoner down the area steps without being ob served either by a man who was walking away in the direction of Pall Mall, or by two chairmen waiting outside a house farther down the square.

The basement of Lady Bellingham’s house was very large very ill-lit, and rambling enough to resemble a labyrinth more nearly than the kitchen-quarters of a well-appointed mansion The cellar destined for Mr Ravenscar’s temporary occupation was reached at the end of a stone-paved corridor, and contained, besides a quantity of store-cupboards, most of Lady Bellingham’s trunks and cloak-bags; a collection of empty band-boxes, stacked up against one wall; and a Windsor chair thoughtfully placed there by Miss Grantham.

Mr Ravenscar was set down on the chair by his panting bearers. Silas Wantage, who had provided himself with the lantern that stood on a table just inside the area-door, critically surveyed him, and gave it as his opinion that he would do. Mr Kennet shook out his ruffles, and smiled upon the victim in a way that made Mr Ravenscar long to have his hands free for only two minutes.

“I’m thinking the second round goes to Deb, Mr Ravenscar. Don’t you be worrying your head, however, for it’s not for long she means to keep you here! We’ll be leaving you now for a while. You will be wanting to think over your situation, I dare swear.”

“Ay, we’d best tell Miss Deb we have him safe,” agreed Silas

Both men then left the cellar, taking the lantern with them and locking the heavy door behind them. Mr Ravenscar was left to darkness and reflection.

Abovestairs, dinner was over, but none of the expectant visitors to the saloons had yet arrived. Mr Kennet strolled into the little back-parlour on the half-landing, where the three ladies were sitting with Kit Grantham, and directed the ghost of a wink at Deborah before going up to shake hands with her brother. It was a little while before any opportunity for exchanging a private word with him occurred, but when he had greeted Kit, and each had asked the other a number of jovial questions, Lady Bellingham recollected that on the previous evening the E.O. table had not seemed to her to be running true, and desired Kennet to inspect it. As he followed her out of the room, he passed Miss Grantham’s chair, smiled down at her, and dropped a large iron key in her lap. She covered it at once with her handkerchief, torn between guilt and triumph, and in a few minutes murmured an excuse, and left the room.

She found Silas Wantage in the front-hall, ready to open the door to the evening’s guests. “Silas! Did you—did you have any trouble?”

“No,” said Wantage. “Not to say trouble. But he displays to remarkable advantage, I will say, nor I don’t hold with hitting him over the head with a cudgel from behind, which was what Kennet done.”

“Oh dear!” exclaimed Miss Grantham, turning pale. “Has he hurt him?”

“Not to signify, he hasn’t. But I would have milled him down, for all he planted me a wisty castor right in the bonebox. What’s to be done now, missie?”

“I must see him,” said Miss Grantham resolutely.

“I’d best come with you, then, and fetch a lantern.”

“I will take a branch of candles down. The servants might notice it if you took the lantern away. But please come with me, Silas!”

“I’ll come right enough, but you’ve no call to be scared, Miss Deb: he’s tied up as neat as a spring chicken.”

“I am not scared,” said Miss Grantham coldly.

She fetched one of the branches of candles from the supper room, and Silas, having instructed one of the waiters to mount guard over the door, led the way down the precipitous stairs to the cellars. He took the big key from her, and flung open the door of Mr Ravenscar’s prison. Mr Ravenscar, looking under frowning brows, was gratified by the vision of a tall goddess in a golden dress, holding up a branch of candles whose flaming tongues of light touched her hair with fire. Not being in a mood to appreciate beauty, he regarded this agreeable picture without any change in his expression.

Miss Grantham said indignantly: “There was no need to leave him with that horrid thing tied round his mouth! No one would hear him in this place, if he shouted for help! Untie ii this instant, Silas!”

Mr Wantage grinned, and went to remove the scarf and the gag. Miss Grantham saw that her prisoner was rather pale, and a good deal dishevelled, and said, in a voice of some concern, “I am afraid they handled you roughly! Silas, please to fetch, glass of wine for Mr Ravenscar!”

“You are too good, ma’am!” said Mr Ravenscar, with bitter emphasis.

“Well, I am sorry if you were hurt, but it was quite your own fault,” said Miss Grantham defensively. “If you had not done such a shabby thing to me I would not have had you kidnapped. You have behaved in the most odious fashion, and you deserve it all!” A rankling score came into her mind. She added: “You did me the honour once, Mr Ravenscar, of telling me that I should be whipped at the cart’s tail!”

“Do you expect me to beg your pardon?” he demanded. “You will be disappointed, my fair Cyprian!”

Miss Grantham flushed rosily, and her eyes darted fire. “I you dare to call me by that name I will hit you!” she said between her teeth.

“You may do what you please—strumpet!” replied Mr Ravenscar.

She took one hasty step towards him, and then checked saying in a mortified tone: “You are not above taking an unfair advantage of me. You know very well I can’t hit you when you have your hands tied.”

“You amaze me, ma’am! I had not supposed you to be restricted by any consideration of fairness.”

“You have no right to say so!” flashed Miss Grantham.

He laughed harshly. “Indeed? You go a great deal too far for me, let me tell you! You got me here by a trick I was fool enough to think even you would not stoop to—”

“It’s not true! I used no trick!”

“What then do you call it?” he jeered. “What of your heart rending appeals to my generosity, ma’am? What of those affecting letters you wrote to me?”

“I didn’t!” she said. “I would scorn to do such a thing!”

“Very fine talking! But it won’t answer, Miss Grantham. I have your last billet in my pocket at this moment.”

“I cannot conceive what you mean!” she exclaimed. “I only sent you one letter in my life, and that I did not write myself as you must very well know!”

“What?” demanded Ravenscar incredulously. “Do you stand there telling me you did not beg me to meet you in the Park this evening, because you dared not let it be known by your aunt that you were ready to come to terms with me?”

An expression of horrified dismay came into Miss Grantham’s face. “Show me that letter!” she said, in a stifled voice.

“I am—thanks to your stratagems, ma’am—unable to oblige you. If you want to continue this farce, you may feel for it in the inner pocket of my coat.”

She hesitated for a moment, and then moved forward, and slid her hand into his pocket. “I do want to see it. If you are not lying to me—”

“Do not judge me by yourself, I beg of you!” snapped Ravenscar.

Her fingers found the letter, and drew it forth. One glance at the superscription was enough to confirm her fears. “Oh, good God! Lucius!” she said angrily. She spread open the sheet, and ran her eyes down it. “Infamous!” she ejaculated. “How dared he do such a thing? Oh, I could kill him for this!” She crushed the letter in her hand, and rounded on Ravenscar, the very personification of wrath. “And you! You thought I would write such—such craven stuff? I would die rather! You are the most hateful, odious man I ever met in my life, and if you think I would stoop to such shabby tricks as these, you are a fool, besides being insolent, and overbearing, and—”

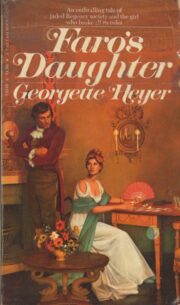

"Faro’s Daughter" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Faro’s Daughter". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Faro’s Daughter" друзьям в соцсетях.