“No?” Ravenscar said, the faintest suggestion of mockery in his voice.

Ormskirk lifted his eyes, and also his quizzing-glass. “My dear Ravenscar! My very dear Ravenscar! I never refuse a challenge. By all means let us measure our skill! But my recollection is that I invited you to come to nay house. Give me the pleasure of your company at dinner tonight, I beg of you!”

Mr Ravenscar accepted this invitation, stayed for a few moments in idle conversation, and presently withdrew, perfectly satisfied with the results of his visit to the club.

He dined tête-à-tête with his lordship, the faded sister who presided over the establishment having gone to spend the evening with friends, his lordship explained. Ravenscar guessed that she had had orders to absent herself, for it was well known that she never received anything but the most cavalier treatment from her brother. Dinner was good, and the wine excellent. Mr Ravenscar, calmly drinking glass for glass with his host, was glad to think that he had a hard head. He might almost have suspected Ormskirk of trying to fuddle his brain a little, so assiduous was he in keeping his guest’s glass filled.

A card-table had been set out in a comfortable saloon on the ground-floor of the house. Several unbroken packs stood ready to hand, and it was not long before the butler carried into the room a tray loaded with bottles and decanters, which he placed upon a side-table. Lord Ormskirk directed him to move a branch of candles nearer to the card-table, and with a smile, and a slight movement of one white hand, invited Ravenscar to be seated.

“What stakes do you care to play for, my dear Ravenscar?” he inquired, breaking open two of the packs at his elbow, and beginning to shuffle the cards.

“It is immaterial to me,” Ravenscar replied. “Let the stakes be what you choose, my lord: I shall be satisfied.”

Lady Bellingham had been correct in saying that his lordship had been having deep doings during the past weeks. He had a bout of ill-luck which had pursued him even into the racing-field, and had gone down to the tune of several thousands. Ravenscar’s challenge could not have been worse timed, but it was not in his lordship’s character to draw back, particularly from an adversary towards whom he felt a profound animosity. It was this animosity, coupled with a gamester’s recklessness, which prompted him to reply: “Shall we say pound points, then?”

“Yes, certainly,” Ravenscar answered.

Ormskirk pushed the pack across to him; he cut for the deal, and lost it. “I hope not an ill-omen!” Ormskirk smiled.

“I hope not, indeed.”

The game opened quietly, no big hands being scored for some little time, and each man bent more upon summing up his opponent than upon the actual winning of points. The rubber went to Ormskirk, but the luck seemed to be running fairly evenly, and there was not much more than the hundred points for the game in it. Ormskirk was inclined to think Ravenscar an over-cautious player: an impression Mr Ravenscar had been at some pains to give him.

At the end of an hour, a glance at the score by his elbow showed his lordship that Ravenscar was steadily creeping ahead. He was too good a card-player not to know when he had met his match, and he recognized in the younger man one who combined his own flair for cards with a greater degree of cool caution. Lord Ormskirk, always playing for the highest prize, too often failed to defeat the major hand by the retention of some small card; again and again, Ravenscar, holding the minor hand, sacrificed a reasonable chance of scoring to spoil a pique which his lordship had felt sure of winning.

In temperament, Ravenscar had the advantage over his opponent. Trying, as a gamester must, to put all thought of his losses out of mind, Ormskirk was yet bitterly conscious of a tightening of the nerves, and still more bitterly aware of Ravenscar’s imperturbable calm. It mattered nothing to a man of his wealth, Ormskirk reflected, whether he won or lost; he could have cursed the misfortune that had caused Ravenscar to challenge him to this meeting at a moment when his own affairs stood in such confusion. The knowledge that he was in a tight corner, and might find himself facing ruin if the evening’s play went heavily against him, could not but affect his nerves, and, through them, his skill. He knew his judgement to be impaired by his desperate need, allowed Ravenscar to win a capotte through a miscalculation, and got up to pour himself out some brandy.

Ravenscar’s eyes flickered towards him, and then dropped again to the pack he was shuffling.

“Brandy?” his lordship said, holding the decanter poised. Ravenscar pushed his empty Burgundy glass a little away from him. “Thank you.”

“You should not have had that capotte,” Ormskirk said abruptly.

“No.”

“I must be out of practice,” Ormskirk said, with a light laugh. “A stupid error to have made! Do not hope for another like it.”

Ravenscar smiled. “I don’t. Such things rarely happen twice in an evening, I find. It is your deal, my lord.”

Ormskirk came back to his chair, and the game proceeded. Once the butler came into the room, to make up the fire. His master, his attention distracted from the play of his cards by the man’s movements, looked up, and said sharply: “That is all. I shall not need you again!”

Outside, in the square, an occasional carriage rumbled over the cobbles, footsteps passed the house, and link-boys could be heard exchanging personalities with chairmen; but as the night wore on the noise of traffic ceased, and only the voice of the Watch was heard from time to time, calling the hour.

“One of the clock, and a fair night!”

It was not a fair night for his lordship, plunging deeper and ever deeper into Ravenscar’s debt. Under his maquillage, his thin face was pale, and looked strained in the candlelight. He knew now that his ill-luck was still dogging him; the cards had been running against him for the past two hours. Only a fool chased his own luck, yet this was what he had been doing, hoping for a change each rubber, risking all on the chance of the big coup which maddeningly eluded him.

A half-consumed log fell out on to the hearth, and lay smouldering there. “I make that fifteen hundred points,” said Ravenscar, adding up the last rubber. He rose, and walked over to the fire to replace the log. “Your luck is quite out: you held wretched cards, until the very last hand.”

“You are a better player than I am,” his lordship said, with a twisted smile. “I am done-up.”

“Oh, nonsense! Play on, my lord; your cards were better at the end. I dare say you will soon have your revenge on me.”

“Nothing would give me more pleasure, I assure you,” said Ormskirk. “But, unhappily, my estates are entailed.”

“Is it as bad as that?” Ravenscar asked, as though in jest.

“Another hour such as the last, and it certainly would be,” replied Ormskirk frankly. “I don’t play if I cannot pay.”

Ravenscar came back to the table, and sat down, idly running the cards through his hands. “If you choose to call a halt, I am very willing. But you hold certain assets I would be glad to buy from you.”

Ormskirk’s thin brows drew together. “Yes?”

Mr Ravenscar’s hard grey eyes lifted from the cards, and looked directly into his. “Certain bills,” he said. “How many and what are they worth?”

“Good God!” said Ormskirk softly. He leaned back in his chair, wryly smiling. “And how came you by that knowledge, my dear Ravenscar?”

“You yourself told me of them, when we walked away from St James’s Square together the other night.”

“Did I? I had forgotten.”

Silence fell. Ormskirk’s eyes were veiled; one of his white hands rhythmically swung his quizzing-glass to and fro on the end of its ribbon. Mr Ravenscar went on shuffling the cards.

“I have a handful of Lady Bellingham’s bills,” his lordship said at last. “Candour, however, compels me to say that they would not fetch quite their face-value in the market.”

“And that is?”

“Fifteen hundred,” said his lordship.

“I am ready to buy them from you at that figure.”

Ormskirk put up his quizzing-glass. “So!” he said. “But I do not think I wish to sell, my dear Ravenscar.”

“You had much better do so, however.”

“Indeed! May I know why?”

“Put brutally, my lord, since your sense of propriety is too nice to allow of your using these bills to obtain your ends, it will be convenient to you, I imagine, to put them into my hands. I shall use them to extricate my cousin from his entanglement. Once that is accomplished, I cannot suppose that Miss Grantham will continue to reject your offer.”

“There is much in what you say,” acknowledged his lordship. “And yet, my dear Ravenscar, and yet I am loath to part with them!”

“Then let us say good night,” Ravenscar replied, rising to his feet.

Ormskirk hesitated, looking at the scattered cards on the table. He was a gambler to the heart’s core, and it irked him unbearably to end the night thus. Ill-luck could not last for ever; it might be that it was already on the turn: indeed, he had held appreciably better cards in that last hand, as Ravenscar had noticed. He hated having to acknowledge Ravenscar to be his superior, too. He could conceive of few things more pleasing than to reverse their present positions. It might well be within his power to do so. He raised his hand. “Wait! After all, why not?” He got up, picked up one of the branches of candles, and carried it over to his writing-table at the end of the room. Setting it down there, he felt in his pocket for a key, and unlocked one of the drawers in the table, and pulled it out. He lifted a slim bundle of papers out, and brought it back to the table, tossing it down on top of the spilled cards. “There you are,” he said. “How fortunate it is that you are less squeamish than I!”

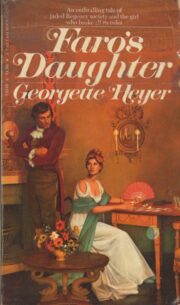

"Faro’s Daughter" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Faro’s Daughter". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Faro’s Daughter" друзьям в соцсетях.