“Tried to bribe you not to marry Adrian, Deb?” asked her aunt. “But how very odd of him, when you had never the lea intention of doing so! What can have put such a notion in his head?”

“I am sure I don’t know, and certainly I don’t care a fig replied Deborah untruthfully. “He had the insolence to offer me five thousand pounds if I would relinquish my pretensions—my pretensions!—to Adrian’s hand and heart!”

Lady Bellingham, over whose plump countenance a hopeful expression had begun to creep, looked disappointed, she said: “Five thousand! I must say, Deb, I think that is shabby!”

“I said that I feared he was trying to trifle with me,” recounted Miss Grantham with relish.

“Well, and I am sure you could not have said anything better, my love! I declare, I did not think so meanly of him!”

“Then,” continued Miss Grantham, “he said he would double that figure.”

Lady Bellingham dropped her reticule. “Ten thousand!” she exclaimed faintly. “No, never mind my reticule, Deb, it don’t signify! What did you say to that?”

“I said, Paltry!” answered Miss Grantham.

Her aunt blinked at her. “Paltry ... Would you—would you call it paltry, my love?”

“I did call it paltry. I said I would not let Adrian slip through my fingers for a mere ten thousand. I enjoyed saying that, Aunt Lizzie!”

“Yes, my dear, but—but was it wise, do you think?”

“Pooh, what can he do, pray?” said Miss Grantham scornfully. “To be sure, he flew into as black a temper as my own, and took no pains to conceal it from me. I was excessively glad to see him so angry! He said—about Ormskirk—Oh, if I were a man, to be able to call him out, and run him through, and through, and through!”

Lady Bellingham, who appeared quite shattered, said feebly that you could not run a man through three times. “At least, I don’t think so,” she added. “Of course, I never was present at a duel, but there are always seconds, you know, and they would be bound to stop you.”

“Nobody would stop me!” declared Miss Grantham bloodthirstily. “I would like to carve him into mincemeat!”

“Oh dear, I can’t think where you get such unladylike notions!” sighed her aunt. “I do trust that you did not say it?”

“No, I said that I thought I should make Adrian a famous wife. That made him angrier than ever. I thought he might very likely strangle me. However, he did not. He asked me what figure I set upon myself.”

Lady Bellingham showed a flicker of hope. “And what answer did you make to that, Deb?”

“I said I should be very green to accept less than twenty thousand!”

“Less than—My love, where are my smelling-salts? I do not feel at all the thing! Twenty thousand! It is a fortune! He must have thought you had taken leave of your senses!”

“Very likely, but he said he would pay me twenty thousand if I would release Adrian.”

Lady Bellingham sank back in her chair, holding the vinaigrette to her nose.

“So then,” concluded Miss Grantham, with reminiscent pleasure, “I said that after all I preferred to marry Adrian.”

A moan from her aunt brought her eyes round to that afflicted lady. “Mablethorpe instead of twenty thousand pounds?” demanded her ladyship, in quavering accents. “But you told me positively you would not have him!”

“Of course I shall not!” said Miss Grantham impatiently. “At least, not unless I marry him in a fit of temper,” she added, with an irrepressible twinkle.

“Deb, either you are mad, or I am!” announced Lady Bellingham, lowering the vinaigrette. “Oh, it does not beat thinking of! We might have been free of all our difficulties! Ring the bell; I must have the hartshorn!”

Deborah looked at her in incredulous astonishment. “Aunt Eliza! You did not suppose—you could not suppose that I would allow that odious man to buy me off?” she gasped.

“Kit might have bought his exchange! Not to mention the mortgage!” mourned her ladyship.

“Kit buy his exchange out of—out of blood-money? He would prefer to sell out!”

“Well, but, my love, there is no need to call it by such an ugly name, I am sure! You do not want young Mablethorpe, after all I...”

“Aunt, you would not have had me accept a bribe!”

“Not an ordinary bribe, dear Deb! Certainly not! But twenty thousand—Oh, I can’t say it!”

“It was the horridest insult I have ever received!” said Deborah hotly.

“You can’t call a sum like that an insult!” protested her ladyship. “If only you would not be so impulsive! Think of poor dear Kit! He is coming home on leave too, and he says he has fallen in love. Was ever anything so unfortunate? It is all very well to talk of insults, but one must be practical, Deb! Seventy pounds for green peas, and here you are throwing twenty thousand to the winds! And the end of it will be that you will fall into Ormskirk’s hands! I can see it all! The only comfort I have is that I shall very likely die before it happens, because I can feel my spasms coming on already.”

She closed her eyes as she spoke, apparently resigning herself to her approaching end. Miss Grantham said defiantly: “I am not in the least sorry. I will make him sorry he ever dared to think I was the kind of creature who would entrap a silly boy into marrying me!”

This announcement roused Lady Bellingham to open her eyes again, and to say in a bewildered way: “But you told me you said you would marry him!”

“I said so to Ravenscar. That is nothing!”

“But I don’t see how he can help thinking it if you told him So!”

“Yes, and I told him also, that I meant to set up my own faro-bank when I am Lady Mablethorpe,” nodded Miss Grantham, dwelling fondly on these recollections. “And I said I should change everything at Mablethorpe. He looked as though he would have liked to hit me!”

Lady Bellingham regarded her with a fascinated stare. “Deb, you were not—you were not vulgar?”

“Yes, I was. I was as vulgar as I could be, and I shall be more vulgar presently!”

“But why?” almost shrieked her ladyship.

Miss Grantham swallowed, blushed, and said in a small-girl voice: “To teach him a lesson!”

Lady Bellingham sank back again. “But what is the use of teaching people lessons? Besides, I cannot conceive what he is to learn from such behaviour! I do hope, my dearest love, that you have not got a touch of the sun! I do not know how you can be so odd!”

“Well, it is to punish him,” said Miss Grantham, goaded. “He will not like it at all when he hears that Adrian is going to marry me. I dare say he will try to do something quite desperate.”

“Offer you more money?” asked Lady Bellingham, once more reviving.

“If he offered me a hundred thousand pounds I would fling it in his face!” declared Miss Grantham.

“Deb,” said her aunt earnestly, “it is sacrilege to talk like that! What—what, you unnatural girl, is to become of me? Only remember that odious bill from Priddy’s, and the wheatstraw, and the new barouche!”

“I know, Aunt Lizzie,” said Deborah, conscience-stricken. “But indeed I could not!”

“You will have to marry Mablethorpe,” said Lady Bellingham despairingly.

“No, I won’t’

“My head goes round and round!” complained her aunt, pressing a hand to her brow. “First you say that Ravenscar will be sorry when he hears you are to marry Mablethorpe, and now you say you won’t marry him!”

“I shall pretend that I am about to marry him,” explained Miss Grantham. “Of course I shall not do so in the end!”

“Well!” exclaimed Lady Bellingham. “That is shabby treatment indeed! I declare it would be quite shocking to serve the poor boy such a trick”

Miss Grantham looked guilty, and twisted her ribbons. “Yes, but I don’t think that he will mind, Aunt Lizzie. In fact, I dare say he will be glad to be rid of me presently, because ten to one he will fall in love with someone else, and I assure you I don’t mean to be kind to him! And in any event,” she added, with a flash of spirit, “it serves him right for having such an abominable cousin”

Chapter 6

When Lord Mablethorpe was admitted to the house in St James’s Square, he was quite as much surprised as delighted to find Miss Grantham in a most encouraging mood. He was so accustomed to her laughing at him, and teasing him for his adoration of her, that he could scarcely believe his ears when, in response to his usual protestations of undying love, she allowed him to take her hand, and to press hot kisses on to her veined wrist.

“Oh, Deb, my lovely one, my dearest! If you would only marry me!” he said, in a thickened voice.

She touched his curly, cropped head caressingly. “Perhaps I will, Adrian.”

He was transported with rapture immediately, and caught her in his arms. “Deb! Deb, you are not funning? You mean it?”

She set her hands against his chest, holding him off a little. He was so young, and so absurdly vulnerable, that she felt compunction stir in her breast, and might have abandoned this way of punishing his cousin had she not recalled Ravenscar’s prediction that this youthful ardour would not last. She knew enough of striplings to be reasonably sure that this was true; and indeed wondered if it would even endure for two months. So she let him kiss her, which he did rather inexpertly, and gave him to understand that she was perfectly serious.

He began at once to make plans for the future. These included a scheme for a secret wedding to be performed immediately, and it took Deborah some time to convince him that such hole-in-corner behaviour was not to be contemplated for an instant. He had a great many arguments to put forward in support of his plan, but was presently brought to abandon it, on the score of its being very uncomplimentary to his bride. This notion, once delicately instilled into his brain, bore instant fruit. He was resolved to follow no course that could suggest to his world that he was in any way ashamed of Miss Grantham. At the same time, he continued to be urgent with Deborah to permit him to announce their betrothal in the columns of the London Gazette, and was with difficulty restrained from running off to arrange for the insertion of his advertisement then and there. Miss Grantham would not hear of it. She pointed out that, as a minor, it would lie in the power of his mother to contradict the advertisement in the next issue of the paper. He agreed to it that this would be very bad, and was obliged to admit that Lady Mablethorpe would be quite likely to take such prompt and humiliating action. But he thought it would be proper to advise his relations of the impending marriage, and begged Deborah’s permission to do so. She was half-inclined to refuse it, but a suspicion that Lady Mablethorpe had probably been behind Mr Ravenscar’s abominable conduct induced her to relent. She said that Adrian might tell his mother, but in strict confidence.

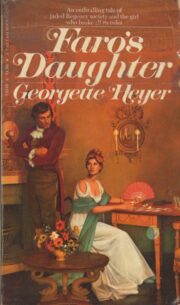

"Faro’s Daughter" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Faro’s Daughter". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Faro’s Daughter" друзьям в соцсетях.