“Why, what should become of you at all?”

“My aunt is quite distracted. There are nothing but bills!”

“Ah, throw them in the fire, me dear.”

“You know well that won’t answer! I wish you will stop casting the bones!”

He gathered them up into the palm of one hand, tossing them into the air, and catching them as they fell. There was a smile in his eyes as he answered: “Your heart’s not in this, is it?”

“Sometimes I think I hate it,” she admitted, sinking her chin into her cupped hands, and glowering. “Oh, the devil, Lucius I’m no gamester!”

“You chose it, me darlin’. I’d say ’twas in your blood.”

“Well, and so I thought, but it’s tedious beyond anything I ever dreamed of! I think I will have a cottage in the country one day, and keep hens.”

He burst out laughing. “God save the hens! And you supping off lobsters every night, and wearing silks, and fallals, and letting the guineas drip through the pretty fingers of you!”

Her eyes twinkled; the corners of her humorous mouth quivered responsively. “That’s the devil of it,” she confessed. “What’s to be done?”

“There’s the suckling,” he drawled. “I doubt he’d be glad to give you your cottage, if it’s that you want, so you might play at keeping farm, like the sainted French Queen, God rest he soul!”

“You know me better!” she said, with a flash. “Do you think I would serve a romantic boy such a turn as that? A rare thing for him to find himself tied to a gamester five years the elder!”

“You know, Deb,” he said, watching the rise and fall of hi dice through half-shut eyes, “there are times I’ve a mind to run off with you meself.”

She smiled, but shook her head. “When you’re foxed, may be.”

His hand shut on the dice; he turned his head to look at her. “Be easy; I’m sober enough. What do you say, me darlin’? Will you throw in your lot with a worthless fellow that will never come to any good in this world, let alone the next?

“Are you offering for me, Lucius?” she demanded, blinking at him.

“Sure I’m offering for you! It’s mad I am entirely, but what of that? Come adventuring with me, me love! I’ll swear you’ve the spirit for it!”

She gave him one of her clear looks. “If I loved you, Lucius; I don’t, you see. Not as your wife, but only as your good friend.”

“Ah well!” he said, tossing up the dice again. “I doubt it’s for the best!”

“Indeed, I don’t think you would make a very good husband,” she said reflectively. “You would be wishing me at the devil before a year was out.”

“I might,” he agreed.

“Besides,” she said practically, “how should marriage wit you help Aunt Lizzie out of her difficulties?”

“Ah, to hell with the old woman! You’re too young to be worrying your head over her troubles, me dear, believe you me!”

“It’s when you talk like that I like you least, Lucius,” she said.

He shrugged. “Have it as you will. What’s it to be? Will you have a roulette table or the noble Earl of Ormskirk?”

“I will have neither!”

“Tell that to your aunt, Deb, and see how she takes it.”

“What do you mean?” she asked fiercely.

“God bless us all, girl, if she were not playing his lordship game for him, what possessed the silly creature to borrow money from him?”

“You are thinking of the mortgage on this house! She had no notion—”

“That, and the bills his lordship bought up, all out of the goodness of his heart, you’ll be asking me to believe.” Her cheeks whitened. “Lucius, he has not done that?”

“Ask the old lady.”

“Oh, poor Aunt Lizzie!” she exclaimed. “No wonder she is so put-about! Of course she would never have the least notion that that horrid man would use them to force me to become his mistress! And I won’t! I’ll go to prison rather!”

“Prison is a mighty uncomfortable place, me dear.”

“He’d not do that!” she said confidently. “This is all conjecture! He has used no threats to me. Indeed, I am very sure he is too proud. But, oh, I would give anything to get those bills out of his hands!”

He threw her an ironical glance. “I’m thinking you’d best ask your rich new friend to buy ’em back for you, me darlin’. It’s delighted I’d be to help you, but my pockets are to let, as well you know.”

“I wish you will not be absurd!” she said crossly. “It’s ten to one I shall never set eyes on Ravenscar again, and if I did—oh, don’t be a fool, Lucius, for I’m in no funning humour!”

The door opened to admit Mortimer. “Mr Ravenscar has called, miss, and desires to see you. I have shown him into the Yellow Saloon.”

“Faith, it’s heaven’s answer, Deb!” said Mr Kennet, chuckling.

“Mr Ravenscar?” repeated Miss Grantham incredulously. “You must have mistaken!”

The butler silently held out the salver he was carrying. Miss Grantham picked up the visiting-card on it, and read in astonishment its simple legend. Mr Max Ravenscar ran the flowing script, in coldly engraved letters.

Chapter 5

Mr Ravenscar was standing by the window in the Yellow Saloon, looking out. He was dressed in topboot; and leather breeches, with a spotted cravat round his throat and a drab-coloured driving-coat with several shoulder-cape reached to his calves. He turned, as Miss Grantham entered, the room, and she saw that some spare whip-lashes were thru; through one of his buttonholes, and that he was carrying a pair of driving-gloves of York tan.

“Good morning,” he said, coming a few paces to meet her, “Do you care to drive round the Park, Miss Grantham?”

“Drive round the Park?” she repeated, in a surprised tone.

“Yes, why not? I am exercising my greys, and came here to beg the honour of your company.”

She was conscious of a strong inclination to go with hint but said foolishly: “But I am not dressed to go out!”

“I imagine that might be mended.”

“True, but—” She broke off, and raised her eyes to his face, “Why do you ask me?” she asked bluntly.

“Why, from what I saw here last night, ma’am, it would appear to be impossible to be private with you under the roof.”

“Do you wish to be private with me, Mr Ravenscar?”

“Very much.”

She was aware of a most odd sensation, as though a obstruction had leapt suddenly into her throat on purpose to choke her. Her knees felt unaccountably weak, and she knew that she was blushing. “But you barely know me!” she manage to say.

“That is another circumstance that can be mended. Come Miss Grantham, give me the pleasure of your company, I beg of you!”

She said with a little difficulty: “You are very good. Indeed I should like to! But I must change my dress, and you will not care to keep your horses standing.”

“You will observe, if you glance out of this window, that my groom is walking them up and down.”

“You leave me nothing to say, sir. Grant me ten minute grace, and I will gladly drive out with you.”

He nodded, and moved to open the door for her. She glanced up at him under her lashes as she passed him and was once more baffled by his expression. He was the strangest creature! Too many men had been attracted to her for her to fail to recognize the particular warm look in a man’s eyes when they fell upon the woman of his fancy. It was not in Mr Ravenscar’s eyes; but if he had not fallen a victim to her charms what in the world possessed him to invite her to drive out with him?

It did not take her long to change her chintz gown for a walking dress. A green bonnet with an upstanding poke, and several softly curling ostrich plumes, admirably framed her face, and set off the glory of her chestnut locks. She was conscious of looking her best, and hoped that Mr Ravenscar would think that she did him credit.

Lady Bellingham, informed of the proposed expedition, wavered between elation and a doubt that her niece ought not to drive out alone with a gentleman she had met but once before in her life; but the obvious advantages of Deborah’s fixing Mr Ravenscar’s interest soon outweighed all other considerations. Lucius Kennet chose to be amused, and to quiz Miss Grantham unmercifully on having made such an important conquest, but she answered him quite crossly, telling him it was no such thing, and that she thought such jests extremely vulgar.

It was consequently with a slightly heightened colour that she presently rejoined Ravenscar in the Yellow Saloon. Glancing critically at her, he was obliged to admit that she was a magnificent creature. He accompanied her downstairs to the front door, where they were met by Kennet, who came lounging across the hall to see them off.

Ravenscar and he exchanged a few civilities, and the groom led the greys up to the door. Mr Kennet inspected them with a knowledgeable eye, while Ravenscar gave Miss Grantham his hand to assist her to mount into the curricle, and said that he should back them to beat Filey’s pair.

They were, indeed, beautiful animals, standing a little over fifteen hands, with small heads, broad chests and thighs, powerful quarters, and good, arched necks.

“Ah, I’ll wager they are sweet goers!” Mr Kennet said, passing a hand over one satin neck.

“Yes,” Ravenscar acknowledged. “They are beautiful steppers.”

He got up into the curricle, while the groom still stood to the greys’ heads, and spread a rug over Miss Grantham’s knees. Taking his whip in his hand, and lightly feeling his horses’ mouths, he nodded to the groom. “I shan’t need you,” he said briefly. “Servant, Mr Kennet.”

Both the groom and Kennet stepped back, and the greys, which were restive, plunged forward on the kidney-stones that paved the square.

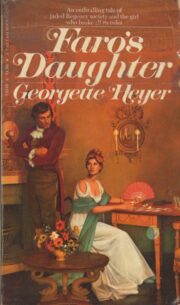

"Faro’s Daughter" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Faro’s Daughter". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Faro’s Daughter" друзьям в соцсетях.