She fell into his arms, sobbing out her relief at seeing him again. "Jack… Jack, my darling…"

He ran his thumb across her bottom lip, then kissed her. She drew back her hand and slapped him hard across the face. "I'm pregnant, you bastard!"

To her surprise, he immediately agreed to marry her, and they were wed three days later at the country home of one of her friends. As she stood next to her handsome bridegroom at the makeshift garden altar, Chloe knew that she was the happiest woman in the world. Black Jack Day could have married anyone, but he had chosen her. As the weeks passed, she determinedly ignored a rumor that his family had disinherited him when he was in Chicago. Instead, she daydreamed about her baby. How exquisite it would be to have the undivided love of two people, husband and child.

A month later, Jack disappeared, along with ten thousand pounds that had been resting in one of Chloe's bank accounts. When he reappeared six weeks later, Chloe shot him in the shoulder with a German Luger. A brief reconciliation followed, until Jack enjoyed another turn of good fortune at the gambling clubs and was off again.

On Valentine's Day 1955, Lady Luck permanently deserted Black Jack Day on the treacherous rain-slicked road between Nice and Monte Carlo. The ivory ball dropped for the last time into its compartment and the roulette wheel jerked to a final stop.

Chapter 2

One of the widowed Chloe's former lovers sent his Silver Cloud Rolls to take her home from the hospital after she'd given birth to her daughter. Comfortably ensconced in its plush leather seats, Chloe gazed down at the tiny flannel-wrapped baby who had been so spectacularly conceived in the center of

Harrods' fur salon and ran her finger along the child's soft cheek. "My beautiful little Francesca," she murmured. "You won't need a father or a grandmother. You won't need anyone but me… because

I'm going to give you everything in the world."

Unfortunately for Black Jack's daughter, Chloe proceeded to do exactly that.

In 1961, when Francesca was six years old and Chloe twenty-six, the two of them posed for a fashion spread in British Vogue. On the left side of the page was the often reproduced black-and-white Karsh photograph of Nita wearing a dress from her Gypsy collection, and on the right, Chloe and Francesca. Mother and daughter stood in a sea of crumpled white backdrop paper, both of them dressed in black. The white paper, their pale white skin, and their black velvet cloaks with flowing hoods made the photograph a study in contrasts. The only real color came from four jolts of piercing green-the unforgettable Serritella eyes leaping out from the page, shimmering like imperial jewels.

After the shock of the photograph had worn off, more critical readers noted that the glamorous Chloe's features were, perhaps, not quite as exotic as her mother's. But even the most critical could find no fault with the child. She looked like a fantasy of a perfect little girl, with a beatific smile and an angel's unearthly beauty shining in the oval of her tiny face. Only the photographer who had taken the picture viewed the child differently. He had two small scars, like twin white dashes, on the back of his hand where her sharp little front teeth had bitten through his skin.

"No, no, pet," Chloe had admonished the afternoon Francesca had bitten the photographer. "We mustn't bite the nice man." She wagged a long fingernail polished a shiny ebony at her daughter.

Francesca glared mutinously at her mother. She wanted to be home playing with her new puppet theater, not having her picture taken by an ugly man who kept telling her not to wiggle. She stubbed the toe of one shiny black patent leather shoe into the crumpled sheets of white backdrop paper and shook loose her chestnut curls from the confines of the black velvet hood. Mummy had promised her a special trip to Madame Tussaud's if she cooperated, and Francesca loved Madame Tussaud's. Even so, she wasn't absolutely certain she'd driven the best bargain possible. She loved Saint-Tropez, too.

After consoling the photographer over his injured hand, Chloe reached out to straighten her daughter's hair and then pulled back with a sudden yelp when she received the same treatment as the photographer. "Naughty girl!" she wailed, lifting her hand to her mouth and sucking on her wound.

Francesca's eyes immediately clouded with tears, and Chloe was furious with herself for having spoken so sharply. Quickly, she pulled her daughter close in a hug. "Never mind," she crooned. "Chloe isn't angry, darling. Bad Mummy. We'll buy you a pretty new dolly on our way home."

Francesca snuggled securely into her adoring mother's arms and peeked up at the photographer through the thick fringe of her lashes. Then she stuck out her tongue.

That afternoon marked the first but not the last time Chloe felt the sting of Francesca's tiny, sharp teeth. But even after three nannies had resigned, Chloe refused to admit that her daughter's biting was a problem. Francesca was merely high-spirited, and Chloe certainly had no intention of earning her daughter's hatred by making an issue out of something so trivial. Francesca's reign of terror might have continued unabated if a strange child had not bitten her back after a tussle over a swing in the park.

When Francesca discovered that the experience was painful, the biting stopped. She wasn't a deliberately cruel child; she just wanted to get her way.

Chloe purchased a Queen Anne house on Upper Grosvenor Street not far from the American embassy and the eastern edge of Hyde Park. Four stories high, but less than thirty feet wide, the narrow structure had been restored in the 1930s by Syrie Maugham, the wife of Somerset Maugham and one of the most celebrated decorators of her time. A winding staircase led from the ground floor to the drawing room, sweeping past a Cecil Beaton portrait of Chloe and Francesca. Coral faux marbre columns framed the entrance to the drawing room, which held a stylish mix of French and Italian pieces as well as several Adam chairs and a collection of Venetian mirrors. On the next floor Francesca's bedroom was decorated like Sleeping Beauty's castle. Against a backdrop of lace curtains swagged with pink silk rosettes and a bed topped by a gilded wooden crown draped with thirty yards of filmy white tulle, Francesca reigned as a princess over all she surveyed.

Occasionally she held court in her fairy-tale room, pouring sweetened tea from a Dresden china pot for the daughter of one of Chloe's friends. "I am Princess Aurora," she announced to the Honorable Clara Millingford on one particular visit, prettily tossing the chestnut curls she had inherited, along with her reckless nature, from Black Jack Day. "You are one of the good women from the village who has come to visit me."

Clara, the only daughter of Viscount Allsworth, had no intention of being a good woman from the village while snooty Francesca Day acted like royalty. She set down her third lemon biscuit and exclaimed,

"I want to be Princess Aurora!"

The suggestion astonished Francesca so much that she laughed, a delicate little peal of silvery sound. "Don't be silly, darling Clara. You have those great big freckles. Not that freckles arenH perfectly nice, of course, but certainly not for Princess Aurora, who was the most famous beauty in the land. I'll be Princess Aurora, and you can be the queen."

Francesca thought her compromise was eminently fair and she was heartbroken when Clara, like so many other little girls who had come to play with her, refused to return. Their abandonment baffled her. Hadn't she shared all her pretty toys with them? Hadn't she let them play in her beautiful bedroom?

Chloe ignored any hints that her child was becoming dreadfully spoiled. Francesca was her baby, her angel, her perfect little girl. She hired the most liberal tutors, bought the newest dolls, the latest games, fussed over her, petted her, and let her do everything she wanted as long as it could not possibly endanger her. Unexpected death had already reared its ugly head twice in Chloe's life, and the thought of something happening to her precious child made her blood run cold. Francesca was her anchor, the only emotional attachment she had been able to maintain in her aimless life. Sometimes she lay sleepless in her bed, her skin clammy, as she envisioned the horrors that could befall a little girl cursed with her father's reckless nature. She saw Francesca jumping into a swimming pool never to come up again, tumbling from a ski lift, tearing the muscles in her legs while practicing ballet, scarring her face in an accident on a bicycle. She couldn't shake the awful fear that something terrible lurked just beyond her vision ready to snatch up her daughter, and she wanted to wrap Francesca in cotton and lock her away in a beautiful silken place where nothing could ever hurt her.

"No!" she shrieked as Francesca dashed from her side and ran down the sidewalk after a pigeon. "Come back here! Don't run away like that!"

"But I like to run," Francesca protested. "The wind makes whistles in my ears."

Chloe knelt down and held out her arms. "Running musses your hair and makes your face all red. People won't love you if you're not pretty." She clasped Francesca tightly in her arms while she uttered this most terrible threat, using it the way other mothers might offer up the horrors of the boogey man.

Sometimes Francesca rebelled, practicing cartwheels in secret or swinging from a tree limb when her nanny's attention was distracted. But her activities were always discovered, and her pleasure-loving mother, who never denied her anything, who never reprimanded her for even the most outrageous misbehavior, became so distraught that she frightened Francesca.

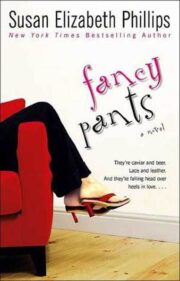

"Fancy Pants" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Fancy Pants". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Fancy Pants" друзьям в соцсетях.