“He has a brooch of mine,” she said, sunk suddenly into gloom. “I staked it, when he wouldn’t accept my vowels, and continue playing. Something told me the luck was about to turn, and so it might have, if Silverdale would but have played on. Not that I cared for losing the brooch, for I never liked it above half, and can’t conceive why I should have purchased it. I expect it must have taken my fancy, but I don’t recall why.”

“Has Evelyn gone off to redeem it?” he interrupted. “Where is Silverdale?”

“At Brighton. Evelyn said there was no time to be lost in buying the brooch back, so off he posted—at least, he drove himself, in his phaeton, with his new team of grays, and he said that he meant to go first to Ravenhurst, which, indeed, he did—”

“Just a moment, Mama!” Kit intervened, the frown returning to his brow. “Why did Evelyn feel it necessary to go to Brighton? Of course he was obliged to redeem your brooch—Silverdale must have expected him to do so!—but I should have supposed that a letter to Silverdale, with a draft on his bank for whatever sum the brooch represented, would have answered the purpose.”

Lady Denville raised large, stricken eyes to his face. “Yes, but you don’t perfectly understand how it was, dearest. I can’t think how I came to be so addlebrained, but when I staked it I had quite forgotten that it was one of the pieces I had had copied! For my part, I consider Silverdale was very well served for having been so quizzy and disobliging about accepting my vowels, but Evelyn said that it was of the first importance to recover the wretched thing before Silverdale discovered that it was only a copy.”

Mr Fancot drew an audible breath. “I should rather think he might say so!”

“But, Kit!” said her ladyship earnestly, “that is much more improvident than anything I should dream of doing! I set its value at £500, which was the value of the real brooch, but the copy isn’t worth a tithe of that! It seems to be quite wickedly extravagant of Evelyn to be squandering such a sum on mere trumpery!”

Mr Fancot toyed for a moment with the idea of explaining to his erratic parent that her view of the matter was, to put it mildly, incorrect. But only for a moment. He was an intelligent young man, and he almost instantly realized that any such attempt would be a waste of breath. So he merely said, as soon as he could command his voice to say anything: “Yes, well, never mind that! When did Evelyn set forth on this errand?”

“Dear one, you cannot have been attending! I told you! Ten days ago!”

“Well, it wouldn’t have taken him ten days to accomplish it, if Silverdale was in Brighton, so it seems that he can’t have been there. Evelyn must have discovered where he was gone to, and decided to follow him.”

She brightened. “Oh, do you think that is what happened? I have been a prey to the most hideous forebodings! But if Silverdale has gone to that place of his in Yorkshire it is very understandable that Evelyn shouldn’t have returned yet.” She paused, considering the matter, and then shook her head. “No. Evelyn didn’t go to Yorkshire. He spent one night at Ravenhurst, just as he told me he would; and then he drove to Brighton. That I do know, for his groom accompanied him; but whether he found Silverdale there or not I can’t tell, because, naturally, Challow doesn’t know. But he returned to Ravenhurst the same day, and stayed the night there. I thought he would do that—in fact, I thought he must have stayed for several days, for he told me that he had matters to attend to at home, and might be absent from London for perhaps as much as a sennight. But he left Ravenhurst the very next morning, and under the most peculiar circumstances!”

“In what way peculiar, Mama?”

“He took only his night-bag with him, and he sent Challow back to London with the rest of his gear, saying that he had no need of him.”

“Oh!” said Kit. His tone was thoughtful, but not astonished. “Did he tell Challow where he was going?”

“No, and that is another circumstance which makes me very uneasy.”

“It need not,” he said, amusement flickering in his eyes. “Did he send his valet back to London too? I take it that Fimber is still with him?”

“Yes, and that is another thing that cuts up my peace! He wouldn’t take Fimber to Sussex: he said there was no room for him in the phaeton, which is true, of course, though it set up all Fimber’s bristles. I must own that I wished he might have found room for him., because I know Fimber will never let him come to harm. Challow is very good too, but not—not as firm! It is the greatest comfort to know that they are both with Evelyn when he goes off on one of his starts.”

“I’m sure it is, Mama,” he said gravely.

“But that’s just it!” she pointed out. “Neither is with him! Kit, it’s no laughing matter! I’m persuaded that some accident has befallen him, or that he’s in some dreadful scrape! How can you laugh?”

“I couldn’t, if I thought it was true. Now, come out of the dismals, Mama! I never knew you to be such a goose! What do you imagine could have happened to Evelyn?”.

“You don’t think—you don’t think that he did see Silverdale, and quarrelled with him, and—and went off alone that day to meet him?”

“Taking his night-bag with him in place of a second! Good God, no! You have put yourself into the hips, love! If I know Evelyn, he’s gone off on a private affair which he don’t want you to know anything about! You would, if he had taken Fimber or Challow with him, and he’s well aware of that. They may be a comfort to you, my dear, but they’re often a curst embarrassment to him! As for accidents—fudge! You’d have been apprised of anything of that nature: depend upon it, he didn’t set out to visit Silverdale without his card-case!”

“No, very true!” she agreed. “I never thought of that!” Her spirits revived momentarily, only to sink again. Her beautiful eyes clouded; she said: “But at such a moment, Kit! When so much hinges upon his presenting himself in Mount Street tomorrow! Oh, no, he could not have gone off on one of his adventures!”

“Couldn’t he?” said Kit. “I wonder! I wish you will tell me a little more about this engagement of his, Mama. You’ve said that there has been no time for him to tell me about it himself, but that’s doing it very much too brown, my dear! There might have been no time for a letter to have reached me, telling me that he had come to the point of offering for this girl; but he never mentioned her name to me in the last letter I had from him, far less the possibility that he would shortly be married; and that, you know, is so unlike him that if anyone but you had broken this news to me I should have thought it a Banbury story. Now, I know of only one reason which would make Evelyn withhold his confidence from me.” He paused, his eyelids puckering, as though he were trying to bring some remote object into focus. “If he were in some fix from which I couldn’t help him to escape—if he were forced into doing something repugnant to him—”

“Oh, no, no, no!” cried Lady Denville distressfully. “It is not repugnant to him, and he was not forced into it! He discussed it with me in the most reasonable manner, saying that while he was resolved on matrimony, he believed it would suit him best to—to enter upon a contract in the old-fashioned way, without violence of feeling on either side. And I must say, Kit, that I think he is very right, for the females he falls in love with are never eligible—in fact, excessively ineligible! Moreover, he is so very prone to fall in love, poor boy, that it is of the first importance to arrange a match for him with a sensible, well-bred girl who won’t break her heart, or come to points with him, every time she discovers that he has a chère amie.”

“Of the first importance—!” he exclaimed. “For Evelyn, of all men! I collect that if she is sufficiently indifferent and well-bred nothing else is of consequence! She may be bran-faced or swivel-eyed or—”

“On the contrary! It goes without saying that there must be nothing in her appearance to give Evelyn a disgust of her; and also that each of them should be ready to like the other.”

He sprang up, ejaculating: “Oh, good God!” He glanced down at her, his eyes very bright, but not with laughter. “You made such a marriage, Mama! Is that what you wish Evelyn to do? Is it?”

She did not answer for a moment; and when she did speak it was with a little constriction. “I didn’t make such a marriage, Kit. Your father fell in love with me. The Fancots said he was besotted, but nothing would turn him from his determination to marry me. And I—well, I was just seventeen, and he was so handsome, so exactly like the heroes schoolgirls dream of—! But the Fancots were right: we were very ill-suited.”

He said, in an altered tone: “I didn’t know—I beg your pardon, Mama!—I shouldn’t have spoken to you so. But you haven’t told me the truth. All this talk of Evelyn’s being resolved on matrimony, as though he were four-and-thirty rather than four-and-twenty—! Flummery!”

“I have told you the truth!” she declared indignantly. She read disbelief in his face, and amended this statement. “Well, some of it, anyway!”

He could not help smiling at this. “Tell me all the truth! A little while ago you said it was my uncle’s fault—also your fault—but in what conceivable way could either of you make it necessary for Evelyn to contract a marriage of convenience? Evelyn doesn’t depend on my uncle for his livelihood, nor is he answerable to him for anything he may choose to do! The only power my uncle has is to refuse to permit him to spend any part of his principal—if he should wish to do so!”

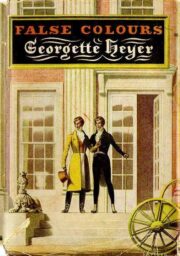

"False Colours" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "False Colours". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "False Colours" друзьям в соцсетях.