“No, Cressy, I do not look charmingly!” said her ladyship firmly. “I don’t know how it is, but no matter how dear they may be, there is something about beads which makes one look shabby-genteel. If I were to wear these, even Emma would think I bought made-up clothes in Cranbourne Alley!”

This seemed an unlikely contingency, but neither Kit nor Cressy ventured to say so. Kit, picking up the topaz necklace, asked, with a sinking heart, if she had bought it at the same time.

“Oh, no, dearest! I bought that long before!” she replied, elevating his spirits for a brief moment. “Weeks ago, when I chose the silk for this underdress! But you may see for yourself that the stones are made to look insipid, worn with this particular shade of yellow. I was afraid they would, but it is such a pretty necklace that I don’t regret having purchased it. If I had some earrings made to match it, I could wear it with a pale yellow evening gown, couldn’t I? But those amber beads I will not wear!”

“No, don’t!” said Kit. “Send them back to the jeweller!”

She considered this suggestion, but decided against it. “No, I have a better notion! I shall give them to your cousin Kate! I don’t suppose you remember her, but she is Baverstock’s second daughter, and never has anything pretty to wear, because your odious Aunt Amelia won’t spend a groat more than she need on her until she has snabbled a husband for Maria—which I shouldn’t think she will ever do, for she’s a plain girl, and has been out for three Seasons already.” She unclasped the amber string, and laid it aside, and said, smiling brilliantly upon her audience: “So it turns out to be for the best, after all, and I must wear my pearls, until I find just what I have in mind! Did you want me particularly, my dears?”

“What did I tell you?” asked Kit, mocking Cressy. “No, Mama: Cressy would have it that it was you who wanted her, to direct invitations for you.”

“I knew there was something I must attend to this morning!” said her ladyship, pleased with this feat of memory. “Oh, dear, what a dead bore it is! I can’t think why I didn’t bring Mrs Woodbury with me, except, of course, that I shouldn’t have known what to do with her here, for one couldn’t expect her to dine in the housekeeper’s room, precisely, and yet—But she is an excellent person, and writes all the invitations, and answers letters for me, and never forgets to remind me of the things I’ve arranged to do!”

Her eyes dancing, Cressy said: “Never mind, ma’am! Only tell me the various directions, and I’ll engage to be quite as excellent a secretary! You made out a list, didn’t you, of all the people you wished to invite?”

“So I did! Not that I wish to invite any of them, because of all the tedious things imaginable Public Days are the worst! However, it would be very uncivil not to hold one, so we must make the best of it. Dear Cressy, how fortunate that you should have remembered that I made up that list! We have only to discover where I put it, and everything will be very simply accomplished—though I hope you don’t think that I mean to let you do more than assist me! I wonder where I did put that list? Not in a safe place, for that is always fatal. Dearest K—kindest Evelyn!” she said, correcting herself with aplomb, “perhaps, if you are not engaged elsewhere, you could direct some of the cards for me!”

“Nothing would afford me greater pleasure, love!” he replied, wondering how long it would be before his irresponsible parent unwittingly exposed him. “But I am engaged elsewhere, and you know well that only you and Kit seem to be able to decipher my handwriting!”

11

The rest of the day passed without untoward incident. Cressy, assisted spasmodically by Lady Denville, directed the invitation cards; Sir Bonamy and Cosmo, after consuming a substantial nuncheon, slept stertorously in the library all the afternoon, their handkerchiefs spread over their faces; the Dowager enjoyed her usual drive with Mrs Cliffe; and Kit, finding his young cousin idling disconsolately in one of the saloons, ruthlessly bore him off for an inspection of the stables, and a tramp across the fields to the stud-farm, where one of my lord’s brood mares had the day before given birth to a promising colt.

The evening was enlivened by the presence of the Squire, Sir John Thatcham, with his lady, and his two eldest offspring: Mr Edward Thatcham, just down from his second year at Cambridge; and Miss Anne, a lively girl, who had gratified her well-wishers by retiring from her first modest Season with a very respectable parti to her credit.

It might have been supposed that a party which included such ill-assorted persons as the Dowager, Sir John and Lady Thatcham, and Sir Bonamy Ripple was foredoomed to failure, for the Dowager, who arrogated to herself an old lady’s privilege of being as uncivil as she chose to anyone whom she considered to be a bore, could almost certainly be depended on to snub the Thatchams; and Sir Bonamy was too much the idle man of fashion to meet with Sir John’s approval. But, in the event, and due, as Cressy recognized with deep respect, to Lady Denville’s unmatched qualities as a hostess, the party was very successful, the only member of it to feel dissatisfaction being Cosmo, who pouted a good deal when he discovered that his sister had excluded him from the whist-table, set up for the Dowager’s edification in a small saloon leading from the Long Drawing-room. Having elicited the information that the Thatchams were very fond of whist, but liked to play together, Lady Denville settled them at the table with the Dowager and Sir Bonamy. No one could have guessed from Sir Bonamy’s good-humoured demeanour that he was in the habit of playing whist in the Duke of York’s company, for five pound points, with a pony on the rubber to make it worth while.

The rest of the party, with the single exception of Cosmo, who said that he was too old for such pastimes, gathered round a large table in the Long Drawing-room to play a number of games which the three youngest members of the party would, in their own homes, have condemned as being fit only for the schoolroom. But Lady Denville, who combined a genius for making her guests feel that she was genuinely happy to entertain them with an effervescent enjoyment of her own parties, rapidly infected the company with her own zest for such innocent pastimes as Command, Cross-Questions, and even Jack-straws. It was all very merry and informal, and when it culminated in a game of speculation Ambrose surprised everyone by displaying an unexpected aptitude for the game, making some very shrewd bids, and quite forgetting the languid air he thought it proper for a young man of mode to assume; and Cosmo, unable to bear the sight of his wife’s improvident play, drew up his chair to the table so that he could advise and instruct her.

At ten o’clock, the Dowager, who had been behaving with great energy and acumen, winning several shillings, and sharply censuring Sir Bonamy for what she considered faults of play, suddenly assumed the appearance of extreme decrepitude, and broke up the game, saying that she was tired, and must go to bed. As soon as she emerged from the saloon, leaning on Sir Bonamy’s arm, Lady Denville rose from the table, and went towards her, saying in her pretty, caressing voice: “Going to retire now, ma’am? I hope you are not being driven away by the noise we have been making!”

“No, I’ve had a very agreeable evening,” replied the Dowager graciously. “No need to leave your game on my account!” She nodded at Cressy. “Stay where you are, child! I can see you’re enjoying yourself, and I don’t want you.”

“Enjoying myself! Nothing of the sort, Grandmama! I’ve fallen amongst sharks, and have lost my entire fortune! What Mr Ambrose Cliffe hasn’t robbed me of has passed into Denville’s possession: I wonder that you should abandon me to such a hard-bargaining pair!” said Cressy gaily.

“I dare say you’ll come about,” said the Dowager. She allowed Lady Denville to take Sir Bonamy’s place, and nodded generally. “I’ll bid you all goodnight. Happy to have made your acquaintance, Lady Thatcham: you, play your cards very tolerably—very tolerably indeed!” She then withdrew, her ebony cane gripped in one claw-like hand, the other tucked in Lady Denville’s arm. She favoured Kit, who was holding open the door for her, with a jocular command not to knock Cressy into horse-nails, but said somewhat snappishly to Lady Denville, as they went slowly along the broad corridor, that she didn’t know why she troubled to escort her to her bedchamber.

“Oh, it isn’t a trouble,” said Lady Denville. “I like to go with you, ma’am, to be quite sure that you have everything just as you prefer it. One never knows that they won’t have sent up your hot milk with horrid pieces of skin in it, or warmed the bed far too early!”

“Lord, Amabel, my woman takes good care of that!” said the Dowager scornfully. She added, in a grudging tone: “Not but what you’re a kind creature—and that I never denied!” She proceeded for some way in silence, but when the upper hall was reached, said suddenly: “That was a good notion of yours, to set the young people to playing silly games. It ain’t often I’ve seen that granddaughter of mine in such a glow of spirits. It’s little enough fun she gets at home.”

“Dear Cressy! I wish you might have heard some of her drolleries! She had us all in whoops, and even succeeded in captivating that dismal nephew of mine!”

The Dowager uttered a crack of mirth. “Him! I’ve no patience with whipstraws, playing off the airs of exquisites.” She paused outside the door of her bedroom. “I’ll tell you this, though, Amabel! I like your son.”

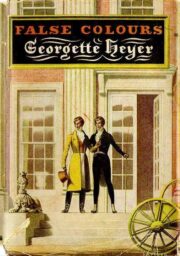

"False Colours" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "False Colours". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "False Colours" друзьям в соцсетях.