“No.”

As he leaves, I glance over my shoulder but there’s nothing there except the blank tan wall and a black-and-white picture of an old actress.

Randy starts digging in. I lean back and join Caleb, shoulders touching, gazing up into the brilliant autumn leaves.

“This was dumb,” Caleb says quietly. “I didn’t even want him in my life in the first place.” He sounds so defeated.

“I’m sorry.” I’m not sure what else to say. I feel bad for suggesting we come here, for getting our hopes up. Exhaustion weighs me down. My legs are sore from all that trudging through sand, and my whole body feels sticky from the salty beach air. As I turn my head to look at Caleb, my neck sticks to the brown vinyl of the booth.

Vinyl.

I sit up. Start running my hands over the seat around me.

“What are you doing?”

“The booth.” I say. “Vinyl.” It doesn’t seem likely. . . . Thousands of people have sat here in the years since Eli was here, but . . . I examine it anyway. Caleb starts to do the same. Running our hands over the contours of the seat, then spaces between cushions, the underside where the seat meets wood. Then I remember Vic’s gaze. I feel behind the curved top of the booth, in the crevice where the vinyl meets the back wall.

My fingers find a sharp edge, a tear in a seam, and a sliver of exposed padding. I press around it . . . and find something hard. I pinch and pull. . . .

And remove an object.

“I found something.” I spin around and hold my palm beneath the table.

It’s a small rectangular case made of opaque plastic, about the length of a credit card, and a half inch thick.

“That’s an old videotape, right?” says Caleb.

“DV tape,” says Randy. “Late nineties, I’d guess. Wait . . .” He looks at us, understanding making him pale even with the red residue. “Is that from . . . Eli?”

“We think so.” Caleb takes it from my hand. Turns it over.

“What the hell is on it?”

Caleb looks at me. Should we tell him? I nod.

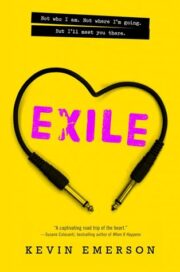

“I think it’s ‘Exile,’” says Caleb.

“EX—” Randy nearly shouts, simultaneously hopping in his seat. He contains himself and leans close. “Exile? You mean the song ‘Exile’? The—”

“Yes, that one. And maybe the other ones, too. ‘Anthem,’ ‘Encore.’”

Randy gazes at the tape again like it’s a sacred artifact.

A message from a dead man.

Vic doesn’t return. We nibble at our food, barely. Caleb holds the tape in a tight fist on the seat between us.

After a few minutes of stunned silence and glances in all directions, wary of our secret being known, we make plans: Randy will search out a DV camcorder in the morning, as soon as vintage stores are open. Caleb and I will meet at his house.

“What about the rest of the band?” I ask him.

“Can you trust the others?” Randy asks. “How long have you known them?”

This is what I am thinking, too, even when I can remove my obvious desire for Val not to be there.

But Caleb shakes his head. “I already blew up one band because of this.” He taps the case. “They probably think tonight was just me being some lead-singer diva. They all should’ve walked offstage when I started that other song, but they stuck it out. They had my back.”

Caleb’s right. “It will be hard to keep this from them,” I say. “It will probably just mess things up further.” When my Val-mistrusting side can keep quiet, it feels like the right move is to tell them. And I don’t mention the other thought on my mind, because I know Caleb isn’t sure what he would do with these lost songs, but I can almost guarantee that the rest of the band will immediately picture what I do: Dangerheart revealing them to the world by playing them live.

Caleb thinks for a second, and then nods. “Let’s tell them.”

13

MoonflowerAM @catherinefornevr 2h

Just another mundane Saturday. #nothingtoseehere

I wake up early Saturday, though it could never be early enough to beat Carlson Squared, professional go-getters. I hear them bustling downstairs, and decide to wait out the fray and check email in bed.

There’s one reply I was hoping for, from Marni Rodgers. She’s in charge of the Harvest Slaughter. People dress like slasher film characters, zombies, or any other ghouls, and the bands dress up, too. We even pick a costume winner, who has the honor of getting Carrie’d onstage (it’s fake blood; one of the PTA dads works for Sony).

Thanks for writing, Summer. We do have one more slot left for the event and we’d be happy to have Dangerheart. They will open for Freak Show. (Did you see them last night?? OMG!) Cheersies! –MR

“Cheersies,” I mutter. I wonder if Marni even saw Dangerheart. Maybe that was for the best. I write back and accept. And then it occurs to me: what if we can also show up there and reveal a lost Allegiance to North song to the world? Can’t jump that gun, though. But at least, in spite of last night, we have a next gig. That is, if the band is still together. I hope Caleb was able to get them to come over.

Mom is already out running errands when I get downstairs. Dad is watching a news talk show while reading from his tablet. On the weekends, he gives himself permission to dress down, but he’s still wearing khakis and shoes and a polo shirt tucked in.

“How was last night?” he asks as I get coffee and toast a bagel.

“Not bad. Kind of a dumb party. Then we went for food.”

“‘We’ being . . . this new band you like?”

“New band I manage,” I say.

“Ah. I thought you weren’t into that anymore?”

“These guys are good,” I say. Then, in case I sound like I’m taking it too seriously for Dad’s taste, I add, “I don’t know, it’s fun.” “Fun” makes it sound like a little hobby and keeps him from inquiring further.

I sit down to eat. Dad joins me. Uh-oh.

“I’ve been thinking. . . . ,” he says. He’s using “Dad-Friend” tone. “How about we go to see a couple schools the weekend after next? You guys have that professional development day, so it’s a long weekend.”

“Oh. Um.”

“I found a couple good law programs and we can make a loop. Stanford Friday and UC Berkeley on Saturday. They offer tours. I may have even scheduled a few, and mentioned your law interest.”

I feel a surge of frustration, wishing once again that Dad might somehow see who I really want to be on his own, but I reply, “Sure.” Except as I’m saying it I remember that the Harvest Slaughter is the same weekend. “Well, but, Stanford? Really? There’s no way I’m getting in there.”

“Cat, come on. You don’t know that. And there’s no harm in looking.”

“Well, okay.” Of course that wasn’t going to work. “But can we be back by Saturday night? There’s a dance.”

“Oh, didn’t realize that. You have a date?”

“Yeah.” Technically, not a lie. I have a date with a band. “I’d really like to go. This year is my last chance for this kind of thing.”

“Ah.” Dad taps on his tablet. “Well, I think we can make it back by the evening. . . .” He doesn’t sound thrilled.

“Are you sure that’s okay?” I ask.

“Yeah, that will be fine.” He sounds disappointed, but I know that he’s sensitive to the idea of me growing up and leaving, and he always wants me to embrace what he thinks of as the traditional high school things. A date to a dance fits his parameters. “That will be fine.” He taps on his tablet. “And is your new band playing the dance?”

He’s also smart enough to read between the lines. “Oh, yeah, I think they are.”

Dad’s brow furrows as he types. “Looks like there’s a different tour time we can get.” His gaze flashes to me. “I just . . . you were so upset a few weeks ago. I mean I know you love music. . . . These band types though . . .” I know what he’ll say next. “I know what they’re like.” He’s referring to how he used to play piano and was in a cover band for, like, three months in high school.

“Dad, it’s no big deal,” I say, a little frustration slipping into my voice. “They’re nice guys. One’s a girl.”

“Okay, but . . .” I can hear Dad shuffling through what to say. “I just picture you with, you know, other kids more like you.”

I shove bagel in and just sort of nod. Then I wait him out. It’s not until Mom is back and I have the car and am driving through the exclusionary gate of the Fronds, our sterile lab of a housing community, that I slam the steering wheel and start swearing at everything from the pedestrians to the clouds in the sky. But mostly at my dad. Kids more like you . . . I know he means well, but for who? For Catherine. He doesn’t even know Summer exists.

As I drive into town, I look around the sprawl of communities just like the Fronds, and more than ever, all I can think is I . . .

Don’t.

Want.

This.

I feel like being here, behind these walls, how could the magic or chance opportunity of life ever find you? This place feels like a choice for safety over possibility, money over art, conformity over individuality. What are these people living for? From here you can’t actually reach for your dreams. Instead, you just idolize those who do, but also celebrate when they fall, when they burn out and self-destruct from trying. That way we have our cautionary tales. They make us feel safe, remind us that we’re not missing anything while we sit inside these prisons.

Or then again maybe I’m wrong. So many people choose this. Choose the Fronds. Choose Catherine. So many people want that for me. Smart, caring people. If I reject it, will I realize some day that I was a fool? Would it be better to be safe and unhappy than in peril and alive?

"Exile" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Exile". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Exile" друзьям в соцсетях.