“How’s it going?” I ask.

“Pretty good,” says Caleb. “Just ran through everything. About to go again.”

“Cool.” I open my notebook.

“Uh-oh,” says Jon, “she’s getting out the ledger.”

“Come on,” I say with a smile, “this is what you pay me for.” I flip to my page of notes from last practice. In between scrawling doodles (not because I’m bored: I like to draw to the music, it helps me think), I have a short list of things to point out. I always like to let a practice go by before mentioning any critique to the band, as some things are just one-time issues, and work themselves out on their own.

They start with “Exit Strategy,” which is upbeat and hyper. It’s a little raw but sounds great.

Next is “Knew You Before.” This is my favorite song so far, and I think it could be a big hit. But as they play it, I hear the main issue that I wrote down last practice. Jon has this pedal board that Caleb nicknamed Mission Control. There are anywhere from five to ten multicolored pedals attached to it at a given practice, cables snaking between them, and he is constantly fidgeting with knobs and buttons. During “Knew You,” he keeps messing with a teal-blue pedal, and his guitar seems to waffle in and out of this time space.

I wait a moment after the song ends, and then say, “So, Jon, what are you going for with that spacey sound?” I’ve learned that Jon is the kind of person who responds to questions. He’s self-critical and will usually intuit what you’re getting at.

“You know,” says Jon with a shrug, already tweaking another dial, “a kind of ethereal wash. Like your arms are out and you’re spinning.”

“Ah.”

He looks up at me. “Was it too much?”

I shrug. “Maybe?” This is a good time to look to Caleb. I don’t mention my critiques to him before I say them, because then it would be like we were ganging up. Also, I try to notice if I’m suggesting something that the band totally doesn’t agree with, because if I am, it’s best to back off and take a different approach.

“It could maybe be a little more direct,” says Caleb.

“I liked when you had more fuzz on the riff in the verse,” Matt adds.

Jon sighs, but it’s not annoyed, rather a scientist hard at work. “Okay, I’ll dial back the tremolo, kick up the overdrive, see if I can make it a little more urgent.”

“Urgent is the perfect word,” I say.

They go through it again and it’s better, but I make sure to ask Jon, “What did you think of it like that?”

“Sure,” he says, “that could work.” Which is close enough to a yes from someone like Jon.

Next, they play “Chem Lab,” which is poppy and about crushing on your lab partner. Caleb’s lyrics are clever and fun: pipettes and titrates and love. But Matt has given it this really complicated beat: busy with lots of accents, when the song feels like it should just flow.

“Matt,” I say when it’s done, “that’s a really cool beat, but it kinda loses me.”

Matt’s eyes always light up when I say his name, except then he immediately looks away, down into the space between his floor tom and bass drum. “It’s just supposed to feel like a loop,” his says, disappointed.

Matt is tougher than Jon. He takes criticism personally, and he’s really proud of his beats. Drummers can get really focused on the sixteenth notes of a song, rather than the song as a whole. But I’ve figured out something that usually works with Matt.

“No, it’s really cool, I just wonder if it’s too syncopated. Probably seems obvious to a drummer. But the other day I heard that song ‘Freeze Dried’ by the Bulbs. Do you know that song?”

“Oh, yeah.” There’s at least a spark of interest in his eyes now.

I know that Matt thinks the Bulbs drummer is great. “Well, that song is sorta like this one, style-wise. He’s doing some pretty cool stuff. It seems kinda laid-back. I don’t know . . . might be worth checking it out.” I actually know exactly which part of that tune I’m hoping he picks up on, but I figure that’s about all that Matt can take for the moment.

“Sure, okay.” He’s still looking down at the floor, but he’s nodding. “I’ll check it out.” This probably means he will.

“It’s a cool beat you’re doing, though,” Caleb adds.

“Thanks,” Matt says quietly.

I sit back and my heartbeat calms. It’s always a little nerve-wracking to try to give feedback, and I’m always glad when it’s over. I listen to the rest of the set, doodling, catching nuances, writing down a note or two for next time but definitely not speaking it, and trying not to watch Caleb too much.

I do have one thing on my list for him, but I’ll wait until after practice to bring it up.

“Why haven’t you showed them ‘On My Sleeve’?” I ask as we walk from his car to Tina’s, each with an arm around the other. We just finished a kiss that caused us to nearly walk into a fire hydrant.

Caleb has been smiling, and as loose as I’ve seen him all day, but mentioning the song suddenly makes him stiffen. “Ah,” he says, “I don’t know if it’s right.”

“Why?” I say. “Because it’s too perfect?” I reach around and squeeze his ribs, but he just flinches a little. He’s got a bag for some reason, this old leather thing that he used for his pedals and cables tonight. I haven’t seen it before.

“It’s not perfect,” he says. He smiles at me, but it’s a lame one, Fret Face in firm control. “I just feel like it’s too personal. I mean, too honest. What fun is that?”

“Um, how about the fact that people are going to totally connect to it? Feel inspired by it?”

“Or laugh at how”—he makes air quotes—“sensitive it is.”

“Oh, please.”

He shakes his head. “It definitely does not seem like a Trial by Fire song.”

“Well, I disagree, and I’m going to keep disagreeing until you change your mind.” I let it go for now though.

I wait until we have bowls of frozen yogurt piled with toppings (peanut-butter cups, gummy bears, chocolate sauce, and whipped cream for me; Caleb is chocolate sprinkles only), and are seated at a table outside to ask: “So, now do I get the dish?”

But Caleb is a long way from his last smile. He’s been tightening up by the second. Does he even remember the joke? Instead, he puts that old gig bag up on the table between us.

And as he opens it, he says, “I got a letter from my dad.”

7

MoonflowerAM @catherinefornevr 10m

Seriously reconsidering whether I believe in ghosts.

“You what?”

“My mom gave this to me on my birthday,” says Caleb, pointing to the bag “It was Eli’s old gig bag. He left it in Randy’s car the day he died.”

“Your uncle Randy knew Eli?”

“Yeah. Randy and my d—Eli were in a band together earlier in high school. That’s how my mom met Eli. Randy wasn’t part of Allegiance, but they still hung out. My mom said that after I was born, Randy was key in getting Eli to pitch in.”

None of this sounds like it makes Caleb very happy.

He continues: “They’d been hanging out in the afternoon, and Eli forgot the bag in the car. Randy wanted me to have it.”

“It’s pretty cool,” I say, running a finger over the cracked seams. “Looks like it’s seen some real action.” There are shreds of a sticker on the side, it maybe says Below Zero, but chunks are missing.

Caleb opens the bag. “It had his old pedals and cables in it. One really cool phaser pedal that I might use. But there’s also a pocket in the lining on the side. I don’t think Randy ever even noticed it.” Caleb zips it open.

And pulls out a piece of paper with a ragged edge.

He places the page between us, turning it around so I can read the scratchy handwriting. “This was written by Eli,” says Caleb. He points to the torn edge. “Looks like he ripped it out of a journal. Do you know about that book called On the Tip of Your Tongue? It’s the collected journals of Allegiance to North. Mom has it at home. I checked this against Eli’s handwriting. It looks exactly the same. But then the last entry in the book from Eli is dated July eleventh, 1998.”

I look at the page. Top corner, a scrawled date: “July fourteenth.”

“That was the night of the Hollywood Bowl show. On that last tour. The last show they ever played in LA.” Caleb’s face is white. “Read it.”

I hunch over it. I’m wary of reading. My insides are spinning. I don’t like this proximity to the words of a dead man.

To you who don’t know me:

I guess it’s fitting that now I wish I could talk to you, wish I could hold you, but of course I can’t. And while I’m off making a mess of everything, you’re somewhere learning your first words, your first steps.

I’d come see you, if I could. Duck out this greenroom door and grab a bus, use a fake name, never come back, but I can’t. I should . . . but I just filled my vein and I don’t want you to see your daddy like this.

Gotta do something though . . .

They’re after me.

I’m not supposed to know but I do. Art becomes business becomes lies. The soul dies. We don’t know it’s dead until it’s long since slipped from us, and we look back and see it waving sadly, as we move on, hollow inside.

I’ve become my faults, can’t stay clean, destroy all the love that comes my way. I know these things. How did I get here? How now brown cow? Life is all just nursery rhymes. You already know everything you need. I’d love to say them with you.

I look up. “I’m not sure he was sober when he wrote this.”

“I know.” Caleb nods at the page and I keep reading.

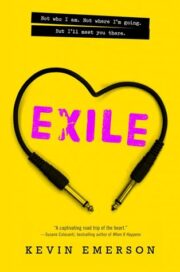

"Exile" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Exile". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Exile" друзьям в соцсетях.