This struggle had been going on in earnest since the Duke of Orléans, lover of the Queen, had been murdered at the orders of the Duke of Burgundy some years before. The King was inclined to favour the Armagnacs which set Burgundy thinking more and more favourably of Henry. Although there was no open alliance he made it clear that he did not consider Henry without claims and the attitude of Burgundy was a source of continual anxiety to the King of France.

Queen Isabeau, who enjoyed intrigue almost as much as she did amorous adventures, at this time decided that she would support Burgundy against her husband and the Orléanists. The only reason she had been with the Orléanists was because her lover had been the Duc d’Orléans. She found it most exciting to send feelers to Burgundy. She was living close to the King – while he enjoyed one of his lucid periods – and was in possession of information which could be useful to Burgundy. As for Burgundy he was only too delighted to have someone as influential as the Queen working for him against his enemies and encouraged the new friendship.

It was hardly to be expected that this should be undiscovered for long, for the Queen was not the only spy in the palace, and the Count of Armagnac soon learned that valuable information was being passed to Burgundy by none other than Isabeau herself. He took the obvious action of discrediting the Queen and this was not difficult, for the Queen’s conduct to say the least was discreditable. Since the murder of Orléans she had had a succession of lovers and the favourite at this time was a certain Louis de Bosredon who was not only her lover but worked with her in getting information to Burgundy.

Armagnac chose the obvious method of revenge. He went to the King and with a show of reluctance implied that not only was Louis de Bosredon the Queen’s lover but that he was acting with her in sending information to Burgundy.

Charles’s temper was unstable. Although at times he was the mildest of men he could suddenly fly into violent rages. He could not help but be aware of his wife’s infidelities. The whole of France had known that the Duc d’Orléans, the King’s own brother, had been her lover. Charles knew it too; but from the moment he had set eyes on Isabeau he had thought her the most beautiful creature he had ever seen, and he still did. His mind was often cloudy even during those times when he was considered well enough to live a normal life; and when he heard that his wife was carrying on an intrigue with Louis de Bosredon in the palace itself he flew into a violent rage.

The Queen was amazed when he approached her. He knew her way of life; everyone knew of it, so why express such surprise? But even she quailed at the storm of invective he let loose upon her.

‘Charles, Charles,’ she murmured, ‘you must calm yourself. If you do not they will take you back to St Pol. Louis is a friend … of yours as well as mine …’

But for once the King was immune to her wiles.

‘You have not heard the last of this,’ he shouted; and he called for the arrest of Louis de Bosredon. That somewhat exquisite gentleman, on his way to the Queen to show her a new pair of embroidered gloves he had had made for himself and to ask her if she would care to patronise the excellent embroiderers he had discovered, was astonished to find himself seized and thrown into a dungeon.

The Queen was temporarily distraught, but she soon assured herself that she would bring the King to reason; and then she would take her revenge on that spy Armagnac. She would rouse the Burgundians to such wrath that there would be massacre in Paris.

It was not quite as easy as usual. The King was adamant in his determination to unmask Louis de Bosredon; he threatened to have him put to the question and the idea of his beautiful body being mutilated sent Louis into panic so that he very quickly admitted everything – his relationship with the Queen and his participation in her spying for Burgundy.

The King ordered that forthwith he be sewn up in a leather sack and thrown into the Seine. A sack on which had been embroidered ‘Let the King’s justice run its course’ was brought and the sentence carried out.

This was not all. Isabeau herself was not to go unpunished. She was banished from the Court and sent to Tours. There she was put into the care of guards who were ordered to watch her night and day and make sure that she neither sent out or received correspondence.

Isabeau thrived on intrigue. She was resourceful and now she decided to ally herself completely with the Duke of Burgundy. She was beautiful, she was beguiling; few men could resist her; certainly not members of the guard. Would one of them do her a service? she wondered. She need not have asked. The chosen man was honoured, he would serve her with his life and it might well be with his life if he were discovered, for what she asked of him was that he should take a message from her to the Duke of Burgundy.

John the Fearless laughed aloud when he received the seal she sent him. He liked the message which told him that if he cared to come to fetch her she would go with him.

To have the Queen in his possession, the Queen his ally! That would be greatly in his favour. He did wonder how he would be able to capture her without storming the château. But she was a resourceful lady. She evidently had ideas.

The messenger went back to tell the Queen that by the time she received his message, the Duke of Burgundy would be two leagues from Tours with a company of men.

Isabeau had her plan ready. She told the guards that she wished to go to Mass at the convent of Marmoutier which was outside the city walls. Her guards conferred together. They were not supposed to leave Tours. Isabeau stamped and raged. Did they forget she was the Queen? She asked only to be able to worship. Was that to be denied her? They would be sorry they treated her so ill. She would not always be in this sorry position and she was not one to forget.

The guards conferred together. What harm could the expedition do if she were well guarded?

So they set out but when they came near the church they saw a company of soldiers approaching. The guards were immediately wary.

‘My lady,’ said their leader, ‘we should return. These soldiers could be Burgundians or English.’

At that moment the Captain who was riding at the head of the soldiers galloped up to her.

He came close to Isabeau’s horse, took her hand and kissed it.

‘I salute you, my lady, on behalf of the Duke of Burgundy.’

‘Where is the Duke?’ she asked.

‘He is close by, my lady.’

‘Then arrest these men who believe themselves to be my captors.’

The astonished guards were bewildered; they could not believe that they had been victims of such a simple ruse.

And there was the Duke of Burgundy himself, riding to the Queen, bowing in his saddle, his eyes alight with pleasure and amusement.

‘Dear cousin,’ cried the Queen, ‘you have delivered me from captivity. We are friends. I shall never fail you. I know you to be a loyal servant of my poor misguided lord and all his family and a true protector of a sad war-torn realm.’

It was a great achievement. Burgundy and the Queen were allies. They set up a Court of Justice to replace that in Paris; Burgundy was now the acclaimed enemy of the King and still more inclined to be on friendly terms with the King’s enemy.

At the same time there was still no open agreement between Henry and Burgundy but they were moving closer together.

It was not until July of 1418 – nearly three years after the battle of Agincourt – that Henry took Rouen. This was the deciding factor and Rouen had held out valiantly realising that as capital of Normandy if it fell to the English that would put the seal of death on French hopes of victory.

It was a particularly heart-rending siege. The inhabitants sent urgent appeals both to the King and the Duke of Burgundy; they sent out from their city any who were unable to fight and this meant that old men, feeble women and young children were wandering in the districts beyond the city walls, dying of starvation; but the citizens were ruthless. They knew they were going to need all the food they had for those who could defend the city. All through the heat of August to the mists of September and the threat of cold in October the siege continued. December had come with all the bitterness of a hard winter. The citizens of Rouen were at the end of their resistance when a message came from Burgundy bidding them treat with the English for the best terms they could get.

It was desertion. Neither the King of France nor the Duke of Burgundy could or would help them.

Henry had expended men and wealth in the siege and he was angry with the citizens for holding out so long. He ordered that all the men should deliver themselves to him and believing this to be certain death the people of Rouen prepared to set fire to their city.

Henry was amazed at a people who could consider burning themselves to death and he immediately granted pardon to all men except a few whom he would name.

Thus on a cold January day Henry made his entry into the city of Rouen and now was the time for the French to come to terms with the English before they took the whole of France and thus made bargaining out of the question.

It was then that Henry set eyes on Katherine and no sooner had he done so than he greatly desired to marry her. He was first of all the soldier, though, and he was not going to concede too much even for Katherine. He had come for the crown of France and would take nothing else.

He was deeply aware of Burgundy. Eager as he was for the Duke’s friendship he was delighted because of the conflict between Burgundy and the King and the Dauphin. He wanted to keep that going.

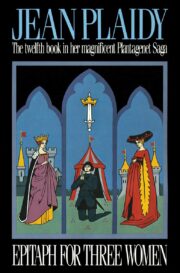

"Epitaph for Three Women" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Epitaph for Three Women". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Epitaph for Three Women" друзьям в соцсетях.