She would tell no one – not even Humphrey – of her visit to Margery. He did not know of her connection with the witch so there was no need to tell him now. Humphrey was unpredictable. Who knew what he would say if he discovered that he had married Eleanor partly because a witch had helped him fall into the trap laid for him.

He was delighted now, of course. He would no longer be overshadowed by an elder brother whom everyone thought was such a virtuous and noble fellow. He was free. He would not have to answer to Bedford for anything again.

People were more subservient to him even than before. He had taken a step up the ladder. It was not an impossibility that he might one day be the King of this country. People had to step warily. They might be talking to the future King.

His vindictive nature set him looking round to see if he had any slights to avenge. The greatest of his enemies was his Uncle Cardinal Beaufort. He wondered how Beaufort was feeling about the death of Bedford. A little uneasy, he was sure. Let him remain so. The Duke of Gloucester was a very powerful man now.

The Cardinal had come back weeping and wailing because of the breaking of the alliance with Burgundy. Gloucester raged against the Duke, calling him traitor. But never mind, they would show him that the desertion of the Duke of Burgundy meant nothing to the English.

‘We shall go in and win back all we have lost,’ he declared.

His Council was uncertain. Beaufort, on whose judgement many of them relied, was of the opinion that they should seek peace. ‘Think of our position there,’ said Beaufort. ‘We have lost a great deal since the siege of Orléans,’ he said. ‘The tide has turned against us and this has ended in the major calamity of the loss of Burgundy’s friendship.’

‘It was not worth much,’ said Gloucester.

‘Your late brothers were of the opinion that it was worth a great deal,’ answered Beaufort.

‘Well, it has proved worthless. Burgundy has deceived us.’

‘He never deceived us. He made the treaty with your brothers, not with England. They are both dead – God help us – and therefore Burgundy can honourably release himself – which he has done. Because of this it is time to think of making peace in France.’

The Cardinal was a traitor, Gloucester declared to the Council. He was working with France. Perhaps he was taking bribes from the French since he was so eager to bring about a peace.

The councillors shrugged their shoulders. There would never be an end to this feud between the Cardinal and his nephew until one of them died.

Gloucester himself wanted to go to France. He would take an army with him, and he promised them that in a short time he would win back all they had lost.

Did any of them believe him? Perhaps not. But it was decided that he should go.

Eleanor was secretly angry. To go out of England was scarcely the way to secure a throne. Moreover she was sure he would not shine as a military hero. He always thought he would, she knew, but there was a world of difference between dreams and reality.

He was delighted to be going to France. Well, let him. He had once again to learn the lesson.

Why did he want to go to France? she mused. Quick recognition? Military glory? Did he really think they were easily acquired? His brothers had been exceptional men – great soldiers, great statesmen. None knew more than Eleanor that her Humphrey was neither. She had to plan for them both. But let him have his game. He would never be satisfied until he had.

He had to snap his fingers at Beaufort. Beaufort thought there should be peace. Therefore Humphrey thought there should be war.

Bedford had won acclaim – in the days before the siege of Orléâns – therefore Humphrey must win fame.

But it would not last.

At least Warwick and Stafford were with him so it might not be a complete débâcle. Perhaps they would save him from that. It might even be a glorious victory. In that case the services of Warwick and Stafford would be forgotten – only to be remembered if there was defeat.

Eleanor was right. There was a quick skirmish in Flanders from which Gloucester emerged without much triumph; then he decided that he could not conduct the war in that fashion. He must go home to consult with the Council.

It was clear that he had had enough of war. He would never excel at it. He wanted to return home to the possibility of becoming King of England and the warm bed of his still attractive wife. So a few months after his departure he was back in England.

It was a very pleasant existence at the manor of Hadham. The passionate love between Queen Katherine and Owen Tudor had developed into a steady devotion. They were completely contented with each other and their happy little family which Katherine had said understandably grew with the years. There were now six-year-old Edmund followed by Jasper a year or so younger, and Owen and Jacina. They lived quietly and simply and it seemed that visitors came less frequently as time passed.

‘Which is how I like it best,’ said Katherine. ‘I must confess, Owen, that I am just a little frightened when people come to Hadham.’

‘They have forgotten us now,’ replied Owen. ‘As long as we do not interfere with the plans of ambitious men, no one thinks of us.’

He did not know how true were his words.

The manor was pleasant, well off the beaten track. Katherine had become the lady of the manor house – she never thought of being royal now. Royal days had not brought her the happiness of this quiet existence. She took great pride in supervising her household. It seemed of the utmost importance whether they should have leyched beef or roast mutton for dinner; and whether it should be fresh or salted fish for Fridays. She always rose at seven and went to the chapel to hear matins in the company of Owen. As soon as Edmund was old enough he should accompany them, she told Owen. He laughed. Their eldest was little more than a baby yet, he reminded her. ‘He will soon be a young man,’ she told him; confident that this quiet life would go on for ever. She had learned to weave and to make up the results of her work into gowns for herself and her family. She could spin like any matron, she said; and she could embroider like any noble lady. She could use the kembyng-stok machine for holding the wool to be combed as efficiently as any of her servants; she could be happily occupied in the still room and exult over her triumphs there and mourn over her failures, of which she proudly stated there were very few. She tended her children as few noble ladies did and rejoiced in the fact she could spend so much time with them. Often she thought of her own bitter childhood, and compared her children’s lot with her own.

‘Lucky lucky little Tudors,’ she thought. Ah, she could have told them of the terrors of listening to the cries of a mad father, of the horrors children could be subjected to through the cruel negligence of a wicked mother.

But I trust they will never know aught of that kind, she often said to herself.

And Owen, he declared he was the happiest man on earth. He was the squire and he was her husband and they had come to terms with their positions so that it did not matter in the least that she had been born a Princess of France.

There were times when she thought of her first-born. Poor little Henry. He was fifteen years old now and they were already thinking of marrying him. She hoped it would not be just yet and that his wife would make him happy when she came. He had been a good and docile boy, and she was quite certain that the Earl of Warwick had made sure he remained so.

So the happy days passed with little news from the outside world. Nor did they want it. All they asked was to go on living in their own little world, enjoying each day as it came to them; content in their love for each other and their growing family.

It was springtime and the blossom was beginning to show on the fruit trees in the orchard and there were black-faced lambs playing in the fields. Katherine and Owen rode out together in the woods and remembered the early days when they had begun to know each other.

Under the trees the bluebells bent their heads to the light winds and the fragrance of damp earth was in the air.

This was happiness, thought Katherine. Everything that had gone before was worth while to have come to this.

She had drawn up her horse and Owen had brought his to wait beside her.

She turned to him and smiled. He understood. It was often thus and there were occasions when they did not feel the need of words.

They would ride back to the house where the smells of roasting meat would tempt their appetites and they would go to the nursery and play awhile with the children and listen to the accounts of nursery drama and comedy. How young Edmund had astonished his tutor with his grasp of reading; how Jasper had written his own name; how young Owen had thrown his fish and eggs onto the floor; how baby Jacina had walked three steps unaided.

All these matters seemed of such moment. Katherine loved the significance of little things. The household affairs seemed to her to be far more important than all those struggles she remembered from her childhood: feuds between noble houses and the ascendancies of the Burgundians over the Armagnacs, her father’s incapabilities and her mother’s lovers.

‘I shall never, never forget,’ she told Owen. ‘And I shall never cease to compare Now with Then.’

He understood as he always did.

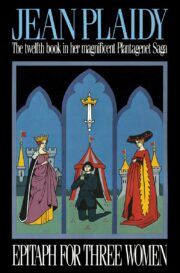

"Epitaph for Three Women" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Epitaph for Three Women". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Epitaph for Three Women" друзьям в соцсетях.