He was astounded and reluctant. Katherine was a Queen, and he could place himself in danger if he performed this ceremony.

He shook his head. ‘My lady, methinks you should inform the Duke of Gloucester of your intentions. If he is agreeable we can perform the ceremony without delay.’

‘I am with child,’ she said. ‘The ceremony must take place at once.’

The priest was horrified. He wanted none of this matter.

‘Are you a man of God?’ demanded the Queen. ‘Will you deny me marriage to the father of my child?’

The priest had no answer. She cajoled; she persuaded; she threatened; and when she pointed out that he was going against the laws of the Church by denying her marriage, at last he promised to perform the ceremony the next day.

Later that day one of her women came to her in a state of great agitation. It was a rumour she had heard.

It was said that the Duke of Gloucester had induced the Parliament to make a law prohibiting any person marrying the Queen Dowager or any lady of high degree without the consent of the King and his Council.

‘This cannot be true,’ she cried. ‘Why … after all this time? Why does he do it now?’

She did not need an answer to that question. It was because he knew.

But Gloucester could only have heard rumours of her liaison with Owen Tudor.

‘What will become of us?’ she cried in terror. But she was not one to give way to despair. Perhaps the horrors of her childhood had prepared her to fend for herself.

Gloucester or no Gloucester she was going to marry Owen Tudor. She was determined that her child would be born in wedlock.

Perhaps, she thought, it was better not to mention to the priest that there was this rumour about her marriage. If he married them in innocence he could not be held to blame. She would tell him that it should be a very secret affair. Only her immediate circle should know it had taken place. They would go on just as before. She would have her baby to care for and she would hope that Gloucester and his Council would lose interest in the mother of the little King.

The ceremony took place in an attic at Hadham and everyone present was sworn to secrecy. The priest asked permission to leave as soon as the marriage had been completed, which Katherine readily gave.

So she was married.

A few days later Gloucester’s new law forbidding her to marry without consent was passed and she was officially informed of it. What could she do? It was too late now.

‘Say nothing,’ she said. ‘These matters pass.’

She was now completely absorbed by her love for Owen and the imminent arrival of their child.

The Duke of Gloucester was a source of great irritation to the Council and it occurred to them that his power could be considerably diminished if the King were crowned. He would then no longer need a Protectorate. The King, though a boy, would rule in his own right. Thus the power of Gloucester could be curbed at one blow.

The Council were in unanimous agreement and on a clear and bright November day young Henry was brought to Westminster.

The Earl of Warwick led him to the high scaffold which had been set up in the Abbey and there he sat looking before him very solemnly, a little sad but conducting himself, as all agreed, with humility and devotion.

The crown was placed on his little head and he knew better now than to complain of its heaviness. He had already learned that although it was sometimes gratifying to be a King it had its drawbacks.

After he had been crowned he must go in procession to Westminster. There three Dukes walked before him carrying three swords which were symbolic of mercy, estate and empire, and Henry himself was led by two Bishops and six Earls with the Barons of the Cinque Ports carrying his pall and the Earl of Warwick his train. Judges, barons, knights and all the dignitaries of the city of London must attend.

The Bishop of Winchester – now a Cardinal – sat on his right hand at the feast and the new Chancellor, John Kemp, was on his other side. It was very formal and Henry was sorry for the Earls of Huntingdon and Stafford because they had to kneel beside him during the feast, one holding the sceptre and the other the sword of state – although he was uncomfortable enough himself in his heavy robes and crown.

And when he was seated and the hereditary champion rode in to challenge anyone who did not agree that Henry was the rightful King, the boy held his breath and looked about him anxiously wondering what would happen if anyone disputed that fact.

No one did and the feast began. Henry wished that he were back in Windsor talking to his mother while Dame Alice and Joan Astley served him with his simple food.

So he was crowned and he was most forcibly reminded that he was King of England.

His uncle Bedford sent messages from France.

He approved of the crowning of the King; he now wished him to be crowned King of France. That was very important. So no sooner had Henry come through one coronation than he was to prepare himself for another.

It was in an atmosphere of mystery that the little Tudor came into the world. It was impossible, of course, to keep his existence completely secret but only those in the household need know.

If visitors came they would not want to see the nurseries. The servants were loyal. They had to be if they would keep their positions and most of them were fond of the Queen.

Katherine had determined that it should all be achieved as comfortably as she could make it. And she did very well. Owen now continued with his duties as squire but he lived in the Queen’s apartments.

They were two happy parents with a baby son.

They discussed what he should be called; Owen suggested Edmund and as Katherine wished all the time to please Owen she agreed to it.

So little Edmund flourished and it was not long before Katherine was once more pregnant.

By that time the strange stories of a peasant girl were reaching England.

She was said to be a virgin endowed with commands from Heaven.

Katherine talked of her a little. She was mildly interested because the girl was French and said to come from Domrémy, a part she knew slightly.

But there was too much to interest her in her own household for her to give much thought to a strange story about a certain girl they were calling Joan of Arc.

Part Two

Joan of Arc

Chapter IX

EARLY DAYS IN DOMRÉMY

SOME sixteen years before the siege of Orléans began Jacques d’Arc and his wife were waiting with mingled excitement and apprehension for the birth of their fourth child. It was not that the newcomer would not be welcome. Far from it. Jacques and his wife Isabelle – known affectionately as Zabillet – loved their children dearly. But times were hard – when had they been otherwise? – and the arrival of a new baby would mean that there was one more mouth to feed.

Jacques originally came from Arc-en-Barrois and having no legal name was called after his birthplace. He had in time found employment about the castle of Vaucouleurs and while there he had met Isabelle Romée. They had fallen in love and married. Isabelle – or Zabillet – though far from rich was not entirely penniless and on her marriage inherited the house in Domrémy where she settled with Jacques, and there the children were born. It was by no means a mansion but it served as a home for them and there was a small piece of land attached which enabled them to grow a few crops and with this and the permission which was given to all the villagers to graze their cattle in the nearby fields they managed to feed and clothe their young family.

Domrémy was situated on the River Meuse about twelve and a half miles from the town of Vaucouleurs and a little nearer to Neufchâteau. Adjoining it was the village of Greux and on the other side of the river was Maxey; a few miles away were Burey-le-Grand and Burey-le-Petit, and away on the heights lay the Château Bourlémont.

Until the wars had flared up again it had been a peaceful spot in which to live. News came slowly; the villagers were like one family, in and out of each other’s houses, sitting at their doors in summer, gathering round the fires in winter, very often in one or other of their dwellings that one fire might serve several, fuel being not always easy to come by. The villagers lived carefully, making the most of everything they could wring from the land and now and then saving a little money to put by for emergencies. There was some excitement when travellers came, which they did now and then, for close by was the great road which had been there since it had been built by the Romans and along this came the messengers to and from the Court; merchants travelled along it too, so Domrémy was not as cut off from the world as some villages might be. Sometimes these travellers stayed at the village and begged a bed for the night and in exchange for that hospitality would give accounts of what was happening in the outside world. Moreover because the house of Jacques d’Arc was more commodious than others in the village he was usually the one to receive the guests.

It was a long low house with a heavy slate roof held up by great beams. In the front there were put two small windows so high that the interior was very dark indeed. The floor was of earth and the house was very sparsely furnished with only the barest necessities – a rough table on trestles, a few stools and spinning wheel and kneading trough; rough partitions divided the rooms. There were window seats in the fireplace and the walls were blackened by years of smoke. But on those walls in each room hung a crucifix, for Jacques and Zabillet were fervently religious and determined to bring up their children to be the same.

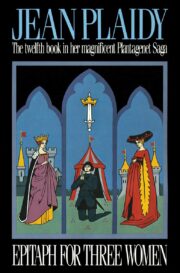

"Epitaph for Three Women" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Epitaph for Three Women". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Epitaph for Three Women" друзьям в соцсетях.