Well not quite, was the answer but one day he would understand. It was often One Day. There was so much he would know then but when would One Day come?

His mother showed him the little velvet cap turned up round the brim above which was a little crown. They put it on his head.

‘I don’t like it,’ he said. ‘It’s heavy. It hurts me.’

‘Come, sweetheart,’ said his mother. ‘You have to wear it, you know.’

‘I shan’t,’ said the King, snatching it off his head.

Stern Alice took it and replaced it. ‘Kings,’ she said very solemnly, ‘have to wear their crowns whether they like them or not.’

That seemed to settle it. He was wondering about Kings and the people who were his and forgot about the crown on his hat.

How the people cheered him! They loved him. He looked so incongruous in his royal robes with the miniature crown on his head and his fat little hand clutching the miniature sceptre. He smiled. They liked him. They were his in some strange way which he would understand One Day.

They took him into St Paul’s and there he was set upon his feet and two lords so magnificently clad that he wanted to stare at them and examine the jewels on their robes walked with him to the high altar.

There was a great deal of talking and it seemed to go on for a very long time but he was very interested in the proceedings and afterwards they led him out of the church and placed him on a beautiful little white horse and he was led through the streets of London. All the traders in the Chepe stood watching him with wonder and several women called out ‘God bless him.’ He was their darling little King. They threw kisses at him.

And he thought then that it was a very nice thing to be a King after all.

John discussed with Anne the letter he had received from the Bishop and the Council.

‘It seems,’ he said, ‘that my brother Gloucester creates trouble wherever he is. I really think it is imperative that I return to England.’

The Earl of Warwick had come to France and he had disturbing stories to tell of the troubles which were working to a climax in England. ‘Your brother,’ he said, ‘is determined to oust Henry Beaufort from the Chancellorship.’

John shook his head. ‘My uncle is a good and honourable man. Would I could say the same for my brother.’

‘The Duke of Gloucester is a very ambitious man, my lord. And when a country has a King who is a minor that can create a difficult situation.’

‘ ’Tis so, my lord Warwick. I would to God my brother Henry had not died and left us this burden.’

‘A tragedy indeed. One so able … so noble … and to die in his prime when he was needed as few have been needed before.’

‘It was a stroke of great misfortune for our country. But we must do what we can to avert disaster.’

‘Which means, my lord, I think that your presence is needed to sort out this trouble.’

‘I am not happy about the state of affairs here in France.’

‘Nay, this affair of Burgundy …’

‘He was my friend, Warwick. His sister is my wife.’

‘Let us be thankful for that, my lord.’

‘Oh, I am fortunate in my marriage. Anne will do all she can to keep her brother at my side. But it is disquieting that Holland and Zealand are already in Burgundy’s hand. When the ex-Bishop of Liège died – most conveniently – Burgundy declared himself the heir and marched in. There remains Hainault and I understand Burgundy is attacking that unhappy land at this time.’

‘What chance has Jacqueline against him?’

‘None.’

‘And she is left alone to face him.’

‘Deserted by my brother. But it would have made no difference if he had been there. Burgundy will conquer Hainault in no time. You see what my brother has done. He has alienated Burgundy from us and at the same time increased Burgundy’s power.’

‘He will be filled with remorse.’

‘Will he? He will not regret the harm he has done me. He will just mourn the loss of the lands he tried to win.’

‘And, my lord, can you leave this field now?’

‘I must, Warwick. I cannot allow dissension in England. What I propose to do is to leave men whom I can trust here while I go to England. I hope my stay there will be brief. But go I must. Warwick, it pleases me to see you here and I am going to appoint you to remain here and with the help of Salisbury and Suffolk to look after matters in my absence.’

Warwick bowed and said that he would do all in his power to serve his country, and Bedford was pleased.

Then he returned to Anne.

‘I wonder how you will like to journey to my country?’ he said.

‘I shall like better to go to your country with you than for you to go there alone,’ she replied.

Their relationship had deepened since he freed the men of D’Orsay at her request. She was with him … even when it meant going against her brother. It had not come openly to that yet. Bedford fervently hoped it never would. But he was grateful for her loyalty and it was a joy to him to be able to talk freely to her. She could sometimes give him good advice for she knew the minds of the French; and she could always offer comfort.

So they left Paris and began the journey to the coast. As he was riding towards the town of Amiens a band of hostile men were waiting for him. They sprang out and attacked his followers – of whom there were not many; he was afraid for Anne and kept her close to him. However, the crowd were only armed with bill hooks – nasty weapons perhaps but not much use against skilled guards – and they were quickly dispersed; but it was a warning always to be on the alert and it brought home the truth that in spite of the fact that he had brought a certain prosperity to France he was still regarded as the usurper.

When he reached England he was greeted by the news that Philip of Burgundy had beaten Jacqueline’s forces and she herself was his prisoner.

Humphrey was feeling decidedly displeased with the manner in which life was going.

He was fast losing interest in Jacqueline. He wished he had never involved himself with her. He did congratulate himself, though, that he had left her in good time. It would have been disastrous if he had been there when Burgundy had marched in. What if the mighty Duke had captured him as well as Jacqueline! He had been wise to listen to Eleanor’s pleadings to return to England. It was the best step he could have taken in this sorry business. He had no time in his ambitious life for lost causes and he was beginning to believe that Jacqueline’s was that.

She had sent him urgent calls for help. But what could he do? She was in Burgundy’s hands now. It would need an army to go to her aid; and was the English Parliament going to grant him the means of raising that? Not likely.

What was occupying him now was his quarrel with his uncle Beaufort. Bastard uncle, he reminded Eleanor. Thinks himself as royal as I am. That was the trouble with these legitimised bastards. They could never forget that they were in truth bastards. It rankled. It made them want to assert themselves.

Beaufort should be ousted from the Chancellorship. Indeed he should be ousted from the country. ‘For,’ he told Eleanor, ‘he is no friend of mine.’

It was not long, of course, before Bedford arranged a meeting with his brother.

He has aged somewhat, thought Humphrey. It is all that responsibility in France. He does not know how to live, this brother of mine. He has the power. There is no question of that. He’s King in all but name, but how does he enjoy himself? That wife of his … Burgundy’s sister. What is she like? There is often little fun in these marriages of convenience.

Bedford was cool. He was indignant of course that he had been brought to England when the situation in France – partly due to Humphrey’s feckless behaviour – was not very secure.

Was he ever going to be allowed to forget that he had offended the all-mighty Burgundy? And now he was at odds with Bastard Beaufort and John did not like that either.

‘It seems,’ said John with that aloof manner which made many men respect him and few like him, ‘that you leave a trail of trouble wherever you go.’

‘It is others who make the trouble.’

‘It seems strange that you are always at the heart of it. Burgundy …’

‘Oh please, brother, let us give Burgundy a rest, eh? I am tired of that sacred name. Believe me I have had the power and importance of the gentleman served to me morning, noon and night.’

‘He happens to be of great importance to our success in France.’

‘I know, I know … and you have married his little sister to placate him. A wise move, brother, and one I should expect of you. I hope the Lady Anne is not too burdensome a duty.’

‘I insist that you do not speak disrespectfully of the Duchess of Bedford. Nor have I come to discuss the disasters your actions have caused in France. That sad story is well known to us all. This quarrel with the Bishop of Winchester must stop.’

‘So Uncle Henry has been whining to you, has he?’

‘I have the report of the Council.’

‘Are they too against me? Oh, sly Uncle Henry has primed them, I don’t doubt.’

‘No sooner do you return to England than you are quarrelling with the Chancellor who, with the Council, has kept order very well during our absence.’

‘Has he? Have they asked the people of London?’

‘The merchants of London are often disgruntled. They resent the taxation which is necessary if we are to bring the crown of France to England and keep it there. It is for you to explain to them the need for taxation. They want us to be victorious. These things have to be paid for. Moreover, do you imagine that if the Bishop ceased to be Chancellor taxes would be any less?’

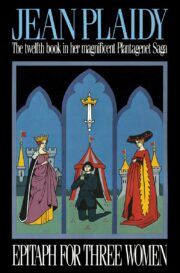

"Epitaph for Three Women" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Epitaph for Three Women". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Epitaph for Three Women" друзьям в соцсетях.