To all this he agreed. He took a fond farewell of her and started out on the journey to Calais. He had a few anxious hours because naturally Eleanor could not ride openly with him. And of course it was expected that she would stay in Holland in attendance on Jacqueline.

They came to an inn where they would spend a night and still she had not joined the party.

He was beginning to fear that she had no intention of coming with him. Could it be that she had found a new lover and had worked to get rid of him? No, they had had such amazing times together; there could not be another person in the world who suited her as he did. She had interested herself so ardently in his affairs. She wanted to be beside him when he took power in England. She had been homesick for England from the moment she had set foot on foreign soil.

But there he was and where was Eleanor?

The horses were in the stables and he with his small band of men went into the inn. He was taken to a room. The innkeeper opened a door and he went in.

Eleanor was lying in the bed.

‘How long you have been in coming,’ she reproached him.

Then he fell upon her and his delight was greater than he had ever known.

Chapter VI

THE DUKE AND THE BISHOP

HENRY BEAUFORT, Bishop of Winchester, was deeply disturbed when he heard that Humphrey of Gloucester was back in England.

He expressed his disquiet to Richard de Beauchamp, Earl of Warwick. Warwick was a man of good reputation, renowned for his honour and selfless devotion to the crown. Henry Beaufort prided himself on a similar loyalty. He was the second son of John of Gaunt and Catherine Swynford and he had never forgotten that he owed his advancement to his relationship with Henry the Fourth who was his half-brother. Their father had expected Henry always to care for the Beaufort branch of the family even though at one time they had been illegitimate – and this Henry had done.

Such a start was something never to be forgotten by a man like the Bishop, and he had sought to serve both his half-brother Henry the Fourth and his nephew Henry the Fifth with devotion. He was now ready to offer that allegiance to Henry the Sixth. He deeply deplored the fact that the new King was a baby and that others should have to be set up to govern during his minority. He had the highest regard for John, Duke of Bedford. It was a different matter with Humphrey.

Now Henry Beaufort was shaking his head and muttering that it was an ill day for England when Gloucester had come amongst them once more.

Warwick agreed. ‘The mission abroad was doomed to failure before it began,’ he said.

‘And in addition is threatening to lose us Burgundy’s support. My Lord Bedford is extremely anxious about the outcome.’

‘And well he might be. Now Burgundy will doubtless walk in and take over Jacqueline’s territories.’

‘I would to God Bedford would return.’

Warwick understood such sentiments. Since Bedford and Gloucester had left the country Beaufort had taken on the responsibility of governing. He had been made Chancellor once more and was held responsible for all the unpopular measures which had had to be taken to support an army in France.

He and Gloucester had been enemies from the time of Henry the Fifth’s death. Beaufort had never wanted Humphrey to have a place on the Council. He was, of course, the brother of the late King and uncle of the reigning one; but Beaufort believed him to be not only selfish and licentious but quite incapable of wise government. He had made this very clear to everyone including Gloucester which naturally did not endear him to the Duke.

At this time Beaufort unfortunately was undergoing a phase of unpopularity in London, and the citizens were expressing their preference for the absent Duke. Beaufort had brought in some unpopular laws and the Londoners were not slow in expressing their irritation with these. They declared he showed more favour to the Flemish traders than he did to the English merchants. Moreover he had approved orders made by the mayor and aldermen restricting the employment of certain labourers.

All the difficulties of city trading including the extorting of taxes were blamed on the Bishop.

‘Bills have been posted on the gates of my palace,’ he told Warwick. ‘The labourers have been meeting and threatening what they will do to me if they lay their hands on me. I tell you, Warwick, there is no joy in this task … even without the presence of the Duke of Gloucester. I have taken the precaution of putting a garrison in the Tower in case there should be trouble. I dread to think of what would happen now if Gloucester rode into London.’

He was soon to discover.

In a few days Gloucester was making it known that he was back and he was going to find out how deeply offended his friends the Londoners were with the Bishop.

In the first place he had sent messages to the Mayor, whom he knew to be on his side with the merchants who believed that the Bishop had treated them badly.

‘My good friend,’ he wrote, ‘we must curb the prejudices of this upstart Bishop against our worthy citizens. I beg of you place a guard on the bridge so that when the Bishop would cross into the city he is prevented from doing so. It will let him know that I am back to uphold the rights of the Londoners.’

The Mayor obeyed Humphrey and when the Bishop was about to make his way into the city he was challenged by men-at-arms who told him that on the orders of the Mayor and the Duke of Gloucester he could not be allowed to enter.

As was inevitable, in spite of the Bishop’s effort to curb it, fighting broke out between the Bishop’s followers and those citizens who were determined to uphold the Mayor’s decision.

Uneasily the Bishop retired. It was even worse than he had imagined. Not content with creating harm to English rule in France by angering the Duke of Burgundy, Gloucester was now set on making trouble at home.

The Bishop sought out Warwick once more. There was no need to explain to him what had happened at the bridge. It was common knowledge.

‘The fighting was fierce while it lasted,’ explained the Bishop. ‘If I had not retired and called off my men there could have been a disastrous riot. Heaven knows how far it would have gone. I wonder, my lord, if you will agree with me that there is only one thing to be done. If you and the Council agree I propose to do it without delay.’

Warwick nodded gravely. ‘I presume you mean that we must ask the Duke of Bedford to return.’

‘That is exactly what I had in mind.’

‘I fear it is necessary. It may be dangerous however for him to leave France at this time when the alliance with Burgundy has been so impaired.’

‘Gloucester has made trouble in France; he could make greater trouble in England.’

‘That is true. And when all is weighed and considered it is England which must be defended first … if it is a matter of making a choice.’

‘I see you are in agreement with me. I must send an urgent message to the Duke of Bedford. However much his presence is needed in France it is even more urgently needed here.’

That very day the Bishop dispatched an urgent message to the Duke of Bedford.

Little Henry was being dressed in a crimson velvet robe. It was a lovely April day and it was decided that he must appear before the people at St Paul’s. The opinion seemed to be that the sight of their baby King might help to appease the angry discontent which was beginning to prevail among the Londoners since the return of Humphrey.

Katherine looked rather sadly at her little son. He would not be four years old until December. It seemed a pity to force him into these ceremonies. She wondered what he thought of all the pomp. He showed no sign of being disturbed by it.

She had tried to explain to him.

‘It is because you are the King, my dearest. The people want to see you.’

‘Are you a King too?’ he asked.

‘No, only boys can be Kings. I am a Queen.’

‘Is Joan a Queen? Is Alice?’

Poor sweet child! What a lot he had to learn.

‘You must smile at the people when they cheer you.’

‘Why will they cheer me?’

‘Because you are the King. Because they like you.’

He smiled then. Dame Alice was a little stern with him. After all, she had been given the right to chastise him. Not that she did very often because he was a good boy, scarcely ever in need of chastisement. And he never bore a grudge against Alice any more than he did against Joan. He loved them dearly. They were part of his life as his mother was. And Owen, of course.

When he sat on his pony Owen led him round the field. He enjoyed that. Owen talked to him in a soft Welsh voice which Henry liked. If Owen stopped talking he would say: ‘Go on, Owen. Go on.’ And Owen would talk about the Welsh mountains and when he was a little boy no bigger than Henry and although Henry did not understand all that was said he liked to hear Owen talk.

His mother liked to be there. She would put her arms about him and smile from him to Owen. He liked the three of them to be together like that.

Now he was going to ride through the streets of London and all the people would come to see him because they liked him, so he had to remember to smile at them and like them.

‘Alice,’ he said, ‘suppose I don’t like them?’

‘You’ll like them,’ said Alice. ‘You’ve got to. They’re your people.’

His people! Like his horse. Like the beads on a stick which his mother had given him. His, like that, he wanted to know.

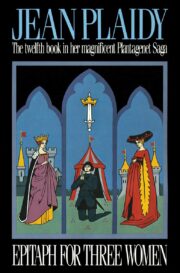

"Epitaph for Three Women" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Epitaph for Three Women". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Epitaph for Three Women" друзьям в соцсетях.