It was a glorious occasion but nothing was more splendid, Katherine decided, than the happiness on the faces of the bride and groom.

The day after the wedding it was announced that ten thousand marks of the ransom were to be remitted as Jane’s dowry and the couple were then free to start their journey to Scotland. At Durham the hostages would have to be delivered into English hands but there seemed to be no difficulty about that.

A few weeks later Katherine said goodbye to her dear friends.

She knew that she was going to be very lonely without them, and when she rode to Hertford where she had decided to rest awhile, she selected Owen Tudor to ride beside her.

‘I shall miss them sorely,’ she told him. ‘But right glad I am to see their happiness. Does it not gladden the heart to see love like that, Owen Tudor?’

He answered quietly: ‘It does, my lady.’

‘That it should have turned out so neatly … that was what I liked. “You must marry a noble English lady,” they said, and there she is … already there. How fortunate they were, Owen; if you can call a man fortunate who has spent the greater part of his life a prisoner.’

‘He is finished with prison now, my lady.’

‘Yes, he gains his rightful place on his throne and his love with him. Do you not think love is the finest thing that can happen to a man and woman, Owen Tudor?’

‘I … I could not say, my lady.’

‘I can … and I will. It is, Owen Tudor. It is!’

Their eyes met and she felt a great happiness creeping over her.

‘They were able to marry,’ he said. ‘They are fortunate indeed.’

‘The happy ending,’ mused the Queen. ‘No … not the ending … Marriage is just the beginning. But they are together … and whatever may come it can be mastered … with a loved one to share it. You think I behave strangely … for a Queen?’ she added.

‘My lady, I think there never was such a Queen as you.’

She turned away. The love affair of James and Jane had affected her deeply. It had made her see what she never dared look at closely before.

Chapter IV

THE MARRIAGE OF BEDFORD

A VERY important ceremony was taking place in the town of Troyes. John, Duke of Bedford, Regent of France was being married to Anne of Burgundy, sister of the great Duke and such an alliance could not fail to raise speculation not only throughout France but in England as well. The English saw it as a master-stroke. Charles of France saw it as disastrous. The old Duke of Burgundy should never have been murdered on the bridge at Montereau. It was deeds like this which were the start of feuds that could go on through centuries; and France at the moment was in need of all the friends she could get. To have alienated Burgundy in such a way was a major disaster. And not only would France lose Burgundy’s friendship: England would gain it.

John himself was filled with complacency. Gloucester’s conduct had been enough to alienate Burgundy altogether. He flattered himself that he had warded that off by this brilliant stroke of genius. John was too shrewd not to realise that the Gloucester affair was not over yet. It would be a blow of great proportions if his brother was ever foolish enough to try to regain Hainault, Holland and Zealand. At the moment he was just a threat. Pray God, thought John, that it remains only that until I can stop the mad affair.

John was philosophical. Life had made him so. He realised that in such a hazardous position as he found himself he could take only one step at a time. This he intended to do. And it was a very clever and happy step he was taking now.

He glanced at Anne riding beside him. The ceremony was over and they were on their way to Paris where the Palace of the Tournelles had been made ready to receive them. Anne was young and beautiful; moreover she was good and gentle, even greater assets. She had placidly agreed to the marriage which showed that she did not regard him with disfavour, and he did not think her willingness had anything to do with politics. There seemed no valid reason why Anne should greatly wish for a friendship between Burgundy and England. So it seemed likely that she did not find his person displeasing.

He was handsome, they said. But did they not often say that of Princes? He had a finely arched nose and well defined chin but he was inclined to put on flesh and his skin was too highly coloured, perhaps the result of much exposure to weather. However he bore a resemblance to his brother Henry and he felt that was in his favour.

Anne was a good deal younger than he was, but that was often the case in marriages such as theirs.

As they rode towards Paris he wanted to reassure her that he would be a good and faithful husband to her.

He said to her: ‘There is some surprise concerning our marriage among the people.’

She answered: ‘It is to be expected.’

‘England and Burgundy … at such a time.’

‘My brother is no friend to Charles of France.’

‘One would not expect him to show friendship towards his father’s murderer.’

Her face was sad. It was tactless of him to have referred to the murder. After all, the victim had been Anne’s father also.

‘I am sorry,’ he said.

She looked at him with surprise.

‘I reminded you of your father,’ he explained. ‘It was tactless of me. It was a great blow to you to lose him.’

‘Murder is terrible. I wish there could be an end to bloodshed.’

‘There will be,’ he promised. ‘It shall be my aim to make France prosperous again and that can only be done through peace.’

She turned to smile at him and he felt a glow of pleasure. She was very beautiful and perhaps she could grow fond of him.

It was a happy man who rode into Paris. This was a great step forward. Married into the House of Burgundy to the sister of the Duke with a dowry of 150,000 golden crowns and the promise that if Philip should die without a male heir the county of Artois should be hers! And even if Philip should have an heir, Anne should have as compensation 1,000,000 golden crowns.

A good marriage. A magnificent dowry, a young and beautiful girl – and the greatest matter for rejoicing was the alliance with Burgundy.

The palace was magnificent and the festivities to celebrate the wedding must be equally so. There were banquets and balls but all the time John was aware of an uneasiness. It seemed difficult for everyone – including Anne – to forget that he was the alien conqueror.

In time, he told himself, it will be forgotten. Time? How long? And he was realist enough to know that even if he kept a firm hold on the government of the country there would always be factions to rise against him. Charles was no mean enemy. He might be weak, impetuous, and often listless but the French still regarded him as their true King and would go on doing so – him and his heirs for centuries to come. Occupation was never easy.

All through the celebrations he was aware of suspicions; he knew that he was watched furtively. He would be strong though. He would be as Henry would have been. Henry had married their Princess; he had done the next best thing: he had married into the House of Burgundy.

He wished he could be sure of them. He even wished he could be sure of Anne.

She was young, inexperienced, an idealist and he found great delight in her. She was docile, eager to please him, but he felt that he did not really know her. He wondered how much Burgundy had had to persuade her to the match. Would he have bothered? Oh yes, indeed, Burgundy saw the marriage as a way of flouting Charles VII and at the moment his bitterness against the murderer of his father was uppermost in his mind.

But John had other matters to occupy him as well as his marriage. A soldier could not give too much thought to his personal affairs except when they were closely connected with his duties. This marriage of course was a very important part of them. But now it was accomplished. He must always try to emulate Henry. Henry had been delighted with Katherine, but he would never have sought the marriage if she had not been the daughter of the King of France.

Messengers were constantly arriving at Les Tournelles. He was eager to know how his forces were faring at D’Orsay for that town had been in a state of siege for more than six weeks and the stubbornness of the townsfolk was an irritation to him for it meant expending so many men and so much ammunition to enforce the siege.

It was time D’Orsay collapsed; it must before long, he assured himself, and then he thought of the siege of Rouen which had caused his brother such anxieties. But it had been successful at last and had indeed been a decisive factor in Henry’s victory. D’Orsay was hardly as important as that but at the same time he was anxiously waiting for news of that beleaguered town.

It was while he was thinking of this matter that news came of the surrender of D’Orsay.

Anne was with him. He smiled at her. ‘At last,’ he cried. ‘Who would have thought such a place could hold out so long.’

She smiled at him sadly. He remembered that smile later. It was not always easy to remember that these people who were holding out against him were her countrymen.

He stood at the window watching the bareheaded prisoners being brought into Paris. These were the men who had made the siege of D’Orsay such a costly matter.

Anne was beside him.

‘You look sad,’ he said.

‘I was thinking of those men. Where are they being taken?’

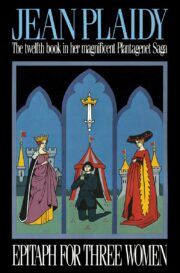

"Epitaph for Three Women" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Epitaph for Three Women". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Epitaph for Three Women" друзьям в соцсетях.