‘Are you in town for long?’

‘No, I am going back to Norfolk. I have work to do there. I believe my manager may be trying to impose on me, and Fanny thinks, as I do, that I should make sure that everything is well.’

My sisters were also there, and Maria said, ‘Fanny seems remarkably interested in Mr. Crawford’s concerns.’

‘Naturally so,’ I replied, but as she seemed out of humor I did not continue that conversation, but turned it instead, saying, ‘How are you enjoying London?’

‘London is wonderful!’ said Julia. ‘There is so much to do, I do not know how we survived at Mansfield. There are parties and balls every night, something different all the time, and the company is very superior.’

‘Superior to what is met with at home?’ I asked her.

She laughed, and said, ‘It cannot compete with Pug, of course, but I believe it compares favorably otherwise.’

‘And yet I am very angry with you,’ Maria said, recovering her good humor. ‘You did not come to my party. It is a pity you missed it. It was a great success. Everyone said so. One of the parties of the year. The house was much admired, and small wonder, for it is one of the finest in town.’

She said nothing of Rushworth, until I enquired after him.

‘Oh, yes, he is very well. He is somewhere about,’ she said, looking round. I followed her eyes and saw them fall on Crawford. A cold look passed between them. I felt a moment of disquiet as I remembered what Fanny had said to me, that there had been something between them at the time of the play, and I wondered if perhaps Fanny had been right, for they did not appear to meet as friends. Maria said nothing, no word of greeting, but merely gave Crawford a nod, and I saw him drawback, surprised. I was sorry for it, for if she felt she had been slighted in the past, what did it matter? She was Miss Bertram no longer; she was Mrs. Rushworth now.

Crawford made her a bow and then moved away.

Maria recovered her composure and I listened to her continuing tales of triumph, interspersed by Julia’s remarks, for some time longer, until, seeing a space free near Mary, I made my way over to her. She was standing in a large group with Lady Stornaway. I waited, hoping for my chance to speak to her alone, but I became more and more disgusted with the conversation, for they were talking about the chances of Miss Dunstan catching the eye of Mr. Croker, a man they thought very desirable, despite his reputation for drunkenness, because he had £20,000 a year.

I was about to move away when Mary detached herself from her companions and said, ‘So, you are here. How pleased I am to see you. You are enjoying yourself, I hope? No, do not tell me. I can see you are not enjoying yourself as much as you do at Mansfield. Dear Mansfield! I must confess, Mr. Bertram, that I miss it. How happy we all were there over the winter. I find myself looking forward to June, when I will be there again.’

‘There is no need for you to wait so long. You will be welcome at Mansfield whenever you return,’ I said to her.

‘But then I would have to disappoint my friends here, for I have promised to stay. An agreement, once reached, must be honored, do you not think?’

‘Indeed it must,’ I said with a smile.

I was about to lead her aside and ask if I might have a private audience with her, when Lady Stornaway joined us. Raising her lorgnette, she asked, ‘And who is this?’

‘Mr. Edmund Bertram,’ said Mary.

‘Indeed. You are a country parson, I understand, Mr. Bertram?’

I felt Mary grow restless beside me.

‘I am.’

‘Well, it is not a bad beginning for a young man of your age, but no doubt you will soon be tired of it and will be seeking advancement in town.’

‘I can assure your ladyship that I am very happy in the country, and have no desire to make my mark in the outside world.’

‘Indeed? How very odd,’ she said. ‘A young man at your time of life has no business in settling for so little, when he could achieve so much. We must encourage him to enlarge his thinking, Miss Crawford.’

‘Believe me, Lady Stornaway, I have been trying,’ said Mary. ‘But, so far, without success.’

‘A young lady of your beauty, wit and intelligence will not be denied for very long. What do you say, Mr. Bertram? It would be ungallant of you to resist such loveliness, would it not?’

Mary looked at me challengingly, and, feeling myself trapped and uncomfortable, I said stiffly, ‘I would not deny Miss Crawford anything I could in reason give her.’

Lady Stornaway took my answer to mean I would seek advancement, and I had nothing more to do but to extricate myself from my predicament as quickly as I could. If only I could extricate Mary from her London friends so quickly, I would be well pleased.

Wednesday 15 March

I saw Tom in the park this morning, where we were both riding, and he hallooed me at once, riding over with his party of friends.

‘Wellmet, little brother.’

He was looking well, and was in good spirits, having won at the races.

‘So, how is the little filly?’ asked Langley. ‘Got her into harness yet?’

I shook my head; Tom was sympathetic; and before I knew it, I was telling him my troubles.

‘Women are the very devil,’ said Langley.

‘Not worth it,’ said Hargate.

‘This one certainly isn’t. Why not marry one of the Miss Owens instead?’ asked Tom. ‘Any one of them would make you a respectable wife.’

‘Because it is Mary I want.’

Hargate nodded sagely.

‘So what are you going to do?’ asked Tom.

‘I will be seeing her tomorrow, but if her mood is still as changeable, and if I have no chance to speak to her alone, I intend to go back to Mansfield and hope for better things once she rejoins her sister there in the summer.’

‘Brother Edmund has a rocky road ahead of him,’ said Tom. ‘We must make sure he enjoys himself this evening, to fortify himself for what is to come.’ He saw my look and said, ‘Never fear, in deference to your tender years and calling, we will be as sober as judges—’

‘Drunk, but not falling down drunk!’ said Hargate.

‘As sober as country parsons,’ amended Tom.

‘Which means snoring drunk,’ said Langley.

‘As sober as young ladies in the seminary,’ reproved Tom.

‘Good God! He means it,’ said Danvers, pulling a tragic face which was, nevertheless, so comical I could not help but laugh.

‘Much better,’ said Tom.

His high spirits lifted my own, and we had a merry day of it.

Thursday 16 March

I dined with the Frasers this evening, but I had no chance to speak to Mary alone, and no desire to do so. Her conversation made it clear that she is torn between a love of wealth and all It can bring, and a desire for something deeper and richer which money cannot buy. But instead of choosing between them, she is tormenting herself because she cannot have both. By the time she returns to Mansfield I hope she will know what she truly desires.

Saturday 18 March

And so, I am back at Mansfield Park, with all the business of the parish to think of, for which I am grateful, as there is nothing I can do now with regard to Mary but wait for her to learn her own mind.

Thursday 23 March

Realizing I had neglected Fanny shamefully, I wrote to her this morning, apologizing for my tardiness in writing and telling her that, if I could have sent a few happy lines, I would have done so straightaway.

I meant to ask her how she was and give her all the London and Mansfield news, but speaking to her, through the medium of the letter, I found myself pouring out my feelings. I am returned to Mansfield in a less assured state than when I left it. My hopes are much weaker, for Mary’s friends have been leading her astray for years. Could she be detached from them! — and sometimes I do not despair of it, for the affection appears to me principally on their side. They are very fond of her; but I am sure she does not love them as she loves you. When I think of her great attachment to you, she appears a very different creature, capable of everything noble, and I am ready to blame myself for a too harsh construction of a playful manner.

I cannot give her up, Fanny. She is the only woman in the world whom I could ever think of as a wife. If I did not believe that she had some regard for me, of course I should not say this, but I do believe it. I am convinced that she is not without a decided preference. You have my thoughts exactly as they arise, my dear Fanny; perhaps they are sometimes contradictory, but it will not be a less faithful picture of my mind. Were it a decided thing, an actual refusal, I hope I should know how to bear it; but till I am refused, I can never cease to try for her. This is the truth.

I have sometimes thought of going to London again after Easter, and sometimes resolved on doing nothing till she returns to Mansfield. But June is at a great distance, and I believe I shall write to her. I shall be able to write much that I could not say, and shall be giving her time for reflection before she resolves on her answer. My greatest danger would lie in her consulting Mrs. Fraser, and I at a distance unable to help my own cause. I must think this matter over a little.

I laid my quill aside, wishing I had Fanny to talk to, instead of having her so far distant. As I read over what I had written, I realized I had spoken of my own concerns and nothing else. Such a letter would surely be enough to tire even Fanny’s friendship, so I picked up my quill and continued with news I knew must give her pleasure.

I am more and more satisfied with all that I see and hear of Crawford. There is not a shadow of wavering. He thoroughly knows his own mind, and acts up to his resolutions: an inestimable quality.

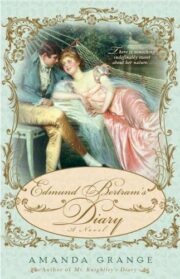

"Edmund Bertram’s Diary" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Edmund Bertram’s Diary". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Edmund Bertram’s Diary" друзьям в соцсетях.