‘Refused him?’ I asked in surprise.

‘Yes. You have always understood her very well, Edmund. It would be an excellent match for her. It would provide her with an establishment, a very good establishment I might say, and a settled and secure future. It is a match I could not have presumed to hope for, as I can give Fanny very little in the way of a dowry, and Crawford is entitled to look much higher, but I am very happy to think of it. He is not only wealthy, he has no vices, and he is an agreeable young man into the bargain. The ladies all seem to like him. And yet she has still refused him. Why do you think she has done it?’

‘I should imagine she was taken by surprise, and did not know what to say.’

‘Perhaps. Although I cannot think why she should be surprised. I have noticed his interest in her with pleasure for some time now, and have hoped it might lead to something. Fanny’s future has often troubled me. Taking her in as we did, we took on responsibility for her, and I did not want to see her dwindle into an old maid, but I confess there have been times when I have not been able to see a different future for her. She is so quiet, and we live so retired, that I knew she would have little opportunity to meet other young people. I was hoping that Maria might ask her to stay, although I also dreaded the idea, for I feared the noise and the bustle of London would not suit her. But if she marries Crawford, she will be well provided for, and I am persuaded she will be happy. And yet she has turned him down.’

‘Fanny thinks so poorly of herself, and her own claims to the ordinary happinesses of life, that, until he proposed, she probably thought his attentions were nothing but kindness.’

‘Then it does not surprise you?’

‘Not at all, and I honor her for it. She could do nothing else. But now that she has been alerted to his preference she will have time to grow used to it and to enjoy it by and by. She deserves to have the love of a good man, one who can give her the elegancies of life, as well as his kindness, his friendship and his affection.’

‘It will be a very big change for her.’

‘Yes, it will. She will go from being our quiet, shy Fanny, to being the centre of attention, but I am sure she will come round. Indeed, I think it must be so. Crawford has been too precipitate, that is all. He has not given her time to attach herself. He has begun at the wrong end. But with such powers of pleasing, he must be able to win her over.’

‘I am glad to hear you say so.’

‘Depend upon it, it will all come right in the end.’

As soon as my father and I returned to the drawing-room for tea, I sat down next to Fanny and took her hand.

‘Fanny, I have been hearing all about your proposal,’ I said warmly. ‘I am not surprised. You have powers of attaching a man that another woman would envy, through your goodness and your purity of spirit. Now I see why Crawford put himself out to help William. He was helping his future brother-in-law!’

‘But I have refused him,’ she said quietly.

‘Of course, for the moment. But when you come to know him better you will see that he is just the sort of man to make you happy.’

She said no more but, feeling sure that she would soon change her mind, I let the matter drop and turned the conversation instead to William.

‘William is coming to stay with us, I understand,’ I said.

She brightened.

‘Yes, he will be here before long. He wants to see us all and thank us for our help in his promotion.’

‘Though it was all Crawford’s doing,’ I put in.

‘He would like to show us his uniform, too, but he is not allowed to wear it except on duty.’

‘Never mind. He will just have to describe it to us and we will then be able to imagine him in all his splendor.’

She talked on happily, looking forward to the day when she will see him again.

Wednesday 11 January

I was so heartened by Mary’s reception of me that I went over to Thornton Lacey this morning to give instructions for the farmyard to be moved, for I wanted to make the place respectable before showing it to Mary.

‘It needs to be over there, behind the copse, out of sight and downwind of the house,’ I said to the men.

They began to work, and I thought how big an improvement it would make to the property. I went into the house and looked into every corner, seeing what needed doing. Over luncheon I asked my father if I could borrow some more men to help me, and he gave me leave to take anyone I wanted.

This afternoon I returned to Thornton Lacey with Christopher Jackson. He followed me in, pausing just inside the front door, then swinging it back and forth and listening to it squeak.

‘This needs attention,’ he said.

‘See to it for me, will you, Jackson?’

He nodded, and we went through to the drawing-room. ‘There are some loose floorboards over here by the window. ’

‘Shouldn’t take too long,’ he said.

As we were about to leave the room he looked at the fire-place.

‘I could make you something better than that, something worth looking at,’ he said. ‘What this room needs is a carved chimney piece.’

I saw at once what he meant. The grate was a good size, and it would repay framing. An ornate chimney piece would give the room an elegant feel, and I could picture Mary sitting in front of it, playing her harp.

‘A good idea. Give me something worth having.’

His eyes lingered on the chimney, and I could tell he already had some ideas in mind. Upstairs, there were some cupboards that needed shelves, and a window frame that needed replacing. When we had been all round the house, I asked him to start work tomorrow. I rode back to Mansfield Park and changed, just in time for dinner. When I went downstairs I discovered that Crawford had called, and my father had invited him to stay for dinner. I wished he had brought his sister with him, but thought that, after all, perhaps it was a good thing he had not, as it would give me an opportunity to see him and Fanny together; if Mary had been present, I would have had eyes only for her.

I was hoping to see some signs of affection for him in Fanny’s face and demeanor, for I was sure that liking for the brother of her friend, gratitude towards the friend of her brother, and sweet pleasure in the honorable attentions of such a man, would combine to spread a warm glow over her face. A blush, a smile, a look of consciousness — these were the things I was expecting, but I did not see any of them. I was surprised but Crawford did not seem disturbed, and he sat beside her with an ease and confidence that spoke of his expectation of being a welcome companion. As he took a seat beside her, I thought her reserve and her natural shyness must soon be worn away. But no such thing. I tried to explain it to myself as embarrassment, but I thought Crawford must be really in love to press his suit with so little encouragement.

After dinner, luckily for Crawford, things improved. When we returned to the drawing-room, Mama happened to mention that Fanny had been reading to her from Shakespeare. Crawford took up the book and asked to be allowed to finish the reading. He began, and read so well that Fanny listened with great pleasure, gradually letting her needlework fall into her lap. At last she turned her eyes on him and fixed them there until he turned towards her and closed the book, breaking the charm.

She picked up her needlework again with a blush, but I could not wonder at Crawford for thinking he had some hope. She had certainly been enraptured by him and I thought that if he could win half so much attention from her in ordinary life he would be a fortunate man. I admired him for persevering, for it showed that he knew Fanny’s value, and knew that she was worth any extra effort he might have to make to overcome her reserve. And I could understand why he would not give her up, for as her needle flashed through her work, her gentleness was matched by her prettiness.

‘That play must be a favorite with you,’ I said to Crawford. ‘You read as if you knew it well.’

‘It will be a favorite, I believe, from this hour,’ he replied. ‘But I do not think I have had a volume of Shakespeare in my hand before since I was fifteen. But Shakespeare one gets acquainted with without knowing how. It is a part of an Englishman’s constitution. His thoughts and beauties are so spread abroad that one touches them everywhere; one is intimate with him by instinct.’

‘To know him in bits and scraps is common enough; to know him pretty thoroughly is, perhaps, not uncommon; but to read him well aloud is no everyday talent.’

‘Sir, you do me honor,’ said Crawford, with a bow of mock gravity.

‘You have a great turn for acting, I am sure, Mr. Crawford,’ said Mama soon afterwards; ‘and I will tell you what, I think you will have a theatre, some time or other, at your house in Norfolk. I mean when you are settled there. I do indeed. I think you will fit up a theatre at your house in Norfolk.’

‘Do you, ma’am? No, no, that will never be,’ Crawford assured her. I was surprised, for if the plays were well chosen, there could be no objection to Crawford setting up a theatre. He had a good income and was entitled to do with it, and his own home, as he wished. It would certainly give him an outlet for his talents, which were of no common sort in that direction.

Fanny said nothing but I am sure she must have guessed that Crawford’s avowal never to have a theatre must be a compliment to her feelings. She had made them known at the time of our disastrous theatrical affair and I was pleased that Crawford was willing to make such a sacrifice. It boded well for Fanny’s future happiness that he put her own wishes above his own. I asked Crawford where he had learnt to read aloud so well and Fanny listened intently to our discussion. I mentioned that it was not taught as it should be, and Crawford agreed.

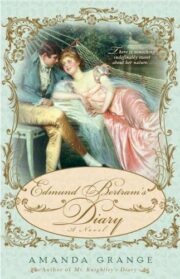

"Edmund Bertram’s Diary" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Edmund Bertram’s Diary". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Edmund Bertram’s Diary" друзьям в соцсетях.