Friday 16 December

This morning my father announced that he intends to give a ball in honor of Fanny and William, and I was relieved and pleased. Relieved, because it would give another turn to my thoughts, which are at present occupied by the serious considerations of my ordination and the torment of wondering whether Mary will marry me. And pleased, because Fanny has little opportunity for dancing, and I want her to be given the pleasure.

My aunt was soon busily deciding that she must take all the care from Mama’s shoulders, and Mama had no objections to make.

My father suggested the twenty-second, a date my aunt declared to be impossible because of the shortness of the notice, but he was firm.

‘We must hold it soon, for William has to be at Portsmouth on the twenty-fourth, so we have not much time left. But I believe we can collect enough young people to form ten or twelve couples next week, despite the shortness of the notice.’

As soon as I had a chance to speak to my father alone, I said, ‘I am very happy at the idea of a ball, for it has been troubling me recently that Fanny has not yet come out.’

My father was surprised to learn of it.

‘Mama felt that her health made it wise to wait until she was older.’

‘Just so,’ he said. ‘Well, this shall be her come-out ball then.’

The invitations were sent out this afternoon, and as I happened to be going past the Parsonage, I took the Crawfords’ and the Grants’ invitation in person. I was pleased to see Mary’s eyes sparkle, but learned it was not with thoughts of the ball. She had just then received a letter from her friends in London, and they had invited her to stay.

‘I thought you were fixed here,’ I said, my spirits sinking.

‘And so I am, but you would not begrudge me a visit to my friends, I am sure,’ she returned.

‘Henry has kindly agreed to remain at Mansfield until January, so that he might convey me to them.’

And so, before January I must offer her my hand, for if I do not, I may miss my chance for many months, or, if she decides to stay in London, forever.

Wednesday 21 December

William and I went into Northamptonshire this morning and I collected Fanny’s chain, which Tom had sent on for me. William was pleased to see it.

‘It is exactly the sort of thing I wanted to buy for Fanny, to go with the amber cross I bought her, but as a midshipman my pay would not stretch so far.’

‘Your time will come,’ I reassured him. ‘When you are a captain, you will be able to buy Fanny as many chains as you wish.’

Our business concluded, William and I rode back to the Park and I took the chain upstairs, thinking to find Fanny in her sitting-room, but she was out. No sooner did I sit down to write her a note, explaining that the chain was hers, and what it was for, than she entered the room. Hardly had I handed it to her when she told me that Mary had already given her a chain for that very purpose. I was heartened to hear of it, and then thought, a moment later, that I should have expected it, because Mary has always been thoughtful, particularly where Fanny is concerned. Fanny said she would return Mary’s gift, but I would not allow it, for it would be mortifying to Mary.

‘But it was given to her by her brother,’ said Fanny. ‘I tried not to take it when I knew, but she insisted, saying he gave her so many things, one more or less did not signify. But I was not comfortable with it then, and I am not comfortable with it now, the more so because it is no longer needed.’

‘Miss Crawford must not suppose it not wanted, not acceptable, at least,’ I said. ‘I would not have the shadow of a coolness arise between the two dearest objects I have on earth. Wear hers for the ball, and keep mine for commoner occasions.’

And so it was settled, and I was heartened as I returned to my room, to know that Mary had so much generosity in her.

Thursday 22 December

It is not only Mary who has generosity in her, it is also her brother, for he has done a very kind thing. He has offered to convey William to London, whither he is bound himself, and has invited him to spend the evening at Admiral Crawford’s. This is just the kind of notice that will help William in his career. To be brought to the attention of an admiral can do him nothing but good. I went down to the Parsonage shortly afterwards, intending to thank Crawford for his kindness, and to engage his sister for the first two dances at the ball. Crawford was from home, but Mary took my thanks very prettily and invited me to sit down.

‘I am here on another errand as well,’ I said. ‘I have come to ask if you would stand up with me for the first two dances.’

‘Certainly,’ she said, adding, ‘For it will be the last time I will ever dance with you.’

‘But why? What is this? You are to return from London, surely? I thought you were only going to pay a visit to your friends.’

‘And so I am, but when I return, you and I will never again be partners.’

I was astonished. ‘How so?’

‘I have never danced with a clergyman, and I never will.’

I could not make her out. Was she joking? If so, it was in very poor taste. If not... At that moment Mrs. Grant came in and I could not say any more about it, but as soon as I returned to the Park I sought out Fanny.

‘I come from Dr Grant’s,’ I said to her. ‘You may guess my errand there, Fanny. I wished to engage Miss Crawford for the two first dances.’

‘And did you succeed?’

‘Yes, she is engaged to me; but...’ I forced a smile. ‘... she says it is to be the last time that she ever will dance with me. She is not serious. I think, I hope, I am sure she is not serious; but I would rather not hear it. For my own sake, I could wish there had been no ball just at — I mean not this very week, this very day; tomorrow I leave home.’

‘I am very sorry that anything has occurred to distress you. This ought to be a day of pleasure. My uncle meant it so.’

‘Oh yes, yes! and it will be a day of pleasure,’ I said, recollecting myself, for the ball was intended for Fanny, and I did not want to spoil her enjoyment. ‘It will all end right. I am only vexed for a moment. I have been pained by her manner this morning, and cannot get the better of it.’

I shook my head as I thought that Mary’s former companions had encouraged her in such shallow opinions and poor taste.

Fanny thought as I did, that Mary’s words were the effect of a poor education.

‘Yes, education! Her uncle and aunt have much to answer for!’

Fanny hesitated.

‘Excuse the liberty; but take care how you talk to me,’ she said gently. ‘Do not tell me anything now, which hereafter you may be sorry for. The time may come—’

‘The time will never come, I have almost given up every serious idea of her,’ I said, shaking my head, for the more I remembered her words and expression, the more I began to feel that I had been a fool to believe I could ever win her. ‘But I must be a blockhead indeed, if, whatever befell me, I could think of your kindness and sympathy without the sincerest gratitude,’ I said to Fanny with a smile.

We were disturbed by the housemaid and, though I would have liked to say more, this prevented further conversation.

I returned to my room to dress for the ball, and my head was full of Mary. I recalled every nuance of her voice and her expression, and by and by I began to think that I had lost heart too easily, and that things were not so very bad. It was playfulness, surely, and not rejection, for even in London there were clergymen, and she could not refuse to dance with them if they asked her. With these happier thoughts in my head I went down to dinner. My humor was so far improved that I was fully able to appreciate Fanny’s beauty and elegance of dress, and to compliment her on it.

‘But what is this?’ I said, seeing her cross hanging from my chain.

‘Miss Crawford’s chain was too big. It would not fit through the hole,’ she said. ‘Yours was just the right fit. I thought it only proper to wear Miss Crawford’s chain also, as she had been kind enough to give it to me, and so I wore it on its own.’

I saw Mary’s chain hanging beside mine.

‘An excellent solution. The amber becomes you, Fanny. You are in looks tonight. You must keep two dances for me; any two that you like, except the first,’ I said to her. No sooner had the ladies withdrawn after dinner than the carriages began to arrive. Mary looked more lovely than ever, her hair arranged in the most becoming style and her dress as faultless as ever. To my delight, Crawford sought out Fanny. They made a handsome couple, and admiring eyes were turned on them. My father looked pleased, and Mama, too, smiled, as Fanny walked on to the floor.

And then I had eyes only for Mary. When she smiled upon me, I banished the last of my fears and gave myself over to an enjoyment of the evening.

‘It was very kind of you to supply Fanny with a chain for her cross. It shows to advantage against her delicate neck,’ she said, as I led her out on to the floor.

‘No kinder than it was of you. I know she wanted to wear your chain with the cross, and was prevented only by its being the wrong size.’

The music started. I bowed, she curtsied, and the dance began.

‘But she is wearing it anyway. I believe a better girl does not exist. She seems to be enjoying herself,’ she said, glancing towards the top of the set, where Fanny and Henry were dancing, adding, ‘though she seems to be looking at William as often as she looks at Henry.’

‘She has seen so little of him these last eight years, I believe she feels she must keep her eyes on him in case he disappears!’

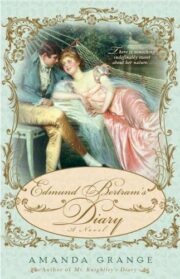

"Edmund Bertram’s Diary" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Edmund Bertram’s Diary". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Edmund Bertram’s Diary" друзьям в соцсетях.