She looked surprised at being consulted on such a trifling matter but the ruse served, for it gave Fanny a few minutes alone with William. By the time the fire had been thoroughly discussed, Fanny and William had joined us, faces aglow, evidently delighted in each other’s company. William proved to be a young man of open, pleasing countenance, and frank but respectful manners, a credit to my father, the Navy, and himself.

My father welcomed him cordially, and though she sprinkled her conversation with, ‘I am sure you will be grateful to your uncle’... ‘benefactor’... ‘stirred himself on your behalf’... my aunt made William welcome, too.

Mama showed him Pug, and before long we were all being entertained by stories of life at sea. Fanny watched William avidly, tracing in his manly face the likeness of the boy she had known. I saw her emotions change from elation at being with him, to perplexity at seeing the changes time had wrought in him, to a welcome recognition of certain expressions and features, and then a more happy, settled joy at being with her beloved William again.

Saturday 10 December

William kept us entertained with stories of his exploits at sea and Fanny lived through every minute of them with him, whether he was telling of his time in the Mediterranean or in the West Indies.

‘My captain sometimes took me ashore, and the places were strange at first, and so were the people. They wore—’

‘I have lost my needle,’ said my aunt. ‘Pray, has anyone seen my needle? I cannot sew without it. Sister, have you seen it? It was here with my sewing not five minutes ago.’

We all stopped and looked for her needle. When it was found, William continued, telling us of a chase as the Antwerp ran down a prize.

‘We were gaining on her every minute, and at last we drew alongside her, and then—’

‘Now where is that button? I know I had it somewhere. Do help me to look for it, Fanny.’

‘The button can wait, I am sure, until we have found out whether the Antwerp captured her prize,’ I said. ‘So, William, you boarded the ship? And what then?’

We sat enraptured as he painted the scene for us, and did it so vividly that Mama murmured,

‘Dear me! How disagreeable. I wonder anybody can ever go to sea.’

‘Why, sister, if no one ever went to sea, what would we do with so many men on land?’ asked my aunt. She turned to William. ‘I hope you are grateful for all the chances you have been given because of the beneficence of your uncle. It is not every young man who has someone to speak for him.’

‘Indeed, I am very sensible of it,’ said William, though he looked surprised to be reminded of it for the third time.

After lunch, I suggested that Fanny should show her brother the Park, and they set out on horseback. As I watched them go I was glad that they would have the afternoon alone with no one to interrupt them. I thought how tender Fanny’s heart was, and how never a brother had been loved as well as William.

Thoughts of brothers and sisters took my own to Miss Crawford and before long I was at the Parsonage, asking after her health. It was much improved, she told me, and smiled at me as she thanked me for taking the trouble to enquire.

Tuesday 13 December

I had a letter from Tom this morning, saying that he would not be able to collect the necklace at once, but promising to send it on as soon as he could.

Wednesday 14 December

The Grants were eager to meet William, and Fanny, having had him to herself for a time, was happy to share him with others, or at least, to allow them to bask in the delight of his presence. That being so, we dined at the Parsonage this evening. Afterwards, Mary played her harp, and I took the opportunity of going to sit beside her. She finished her air, and after I had complimented her on her playing, we began to talk.

‘How happy Fanny is,’ she said, glancing towards the side of the room where Fanny sat, with face aglow, watching and listening to William. ‘I am sure I have never looked at Henry like that.’

‘But perhaps you would if you had not seen him for years, and had been parted when you were ten years old.’

‘I am glad for her. She has a good heart, and she deserves her happiness.’

This could not help but warm me, and her brother warmed me more when he offered William a horse so that he could join us in our ride tomorrow.

Fanny’s face was a mixture of heartfelt gratitude for such kindness to her brother, and fear that he would take a fall.

‘Nonsense!’ said William. ‘After all the scrambling parties I have been on, the rough horses and mules I have ridden, and the falls I have escaped, you have nothing to fear.’

‘Do not worry, Miss Price. I will bring him back to you in one piece,’ said Crawford indulgently. The party broke up in good humor, with an arrangement for us all to dine together tomorrow.

Thursday 15 December

We had a fine day’s sport, and once Fanny saw William come home safely again she was able to value Crawford’s kindness as it should be valued, free of the taint of fear. She was so much reassured by William’s return, without so much as a scratch, that she was able to smile when Crawford said, during dinner at the Parsonage, ‘You must keep the horse for the duration of your visit, Mr. Price.’

‘I thought your brother was going to return to his estate?’ I asked Mary.

‘He was, but he has changed his mind. We have Fanny and William to thank for keeping him here,’ she said. ‘He has decided to stay indefinitely.’

Crawford looked round.

‘What was that? Did someone say my name?’

‘I was telling Mr. Bertram that you had decided to stay with us instead of returning to your estate.’

‘Yes, indeed. I find the place suits me. When I was out riding this morning, I found myself in Thornton Lacey,’ he went on. ‘Is not that the living you are to have, Bertram?’

‘It is. And how did you like what you saw?’ I asked.

‘Very much indeed. You are a lucky fellow,’ he said, adding satirically, ‘there will be work for five summers at least before the place is livable.’

‘No, no, not so bad as that!’ I protested. ‘The farmyard must be moved, I grant you; but I am not aware of anything else. The house is by no means bad, and when the yard is removed, there may be a very tolerable approach to it. I think the house and premises may be made comfortable, and given the air of a gentleman’s residence, without any very heavy expense, and that must suffice me.’ I could not help adding, with a glance at Miss Crawford, ‘And, I hope, may suffice all who care about me.’

‘I have a mind to take something in the neighborhood myself,’ said Crawford. ‘It would be very pleasant to have a home of my own here, for in spite of all Dr Grant’s very great kindness, it is impossible for him to accommodate me and my horses without material inconvenience. will you rent me Thornton Lacey?’ he asked me.

My father replied that I would be residing there myself, which surprised Crawford, who had thought I would claim the privileges without taking on the responsibilities of the living.

‘Come as a friend instead of a tenant,’ I said. ‘Consider the house as half your own every winter, and we will add to the stables on your own improved plan, and with all the improvements that may occur to you this spring.’

Crawford said he had half a mind to take me up on it, but the conversation progressed no further for William began talking of dancing, and it captured the interest of everyone present.

‘Are you fond of dancing, Fanny?’ he asked, turning towards her.

‘Yes, very; only I am soon tired,’ she confessed.

‘I should like to go to a ball with you and see you dance. Have you never any balls at Northampton? I should like to see you dance, and I’d dance with you if you would, for nobody would know who I was here, and I should like to be your partner once more. We used to jump about together many a time, did not we? When the hand-organ was in the street? I am a pretty good dancer in my way, but I dare say you are a better.’ And turning to my father, who was now close to them, said, ‘Is not Fanny a very good dancer, sir?’

‘I am sorry to say that I am unable to answer your question. I have never seen Fanny dance since she was a little girl; but I trust we shall both think she acquits herself like a gentle-woman when we do see her, which, perhaps, we may have an opportunity of doing ere long.’

‘I have had the pleasure of seeing your sister dance, Mr. Price,’ said Crawford, leaning forward, ‘and will engage to answer every inquiry which you can make on the subject, to your entire satisfaction.’

Fanny flushed to hear herself so flatteringly spoken of. Fortunately for her modesty the conversation moved on to balls my father had at ended in Antigua. So engrossed were we all in listening to him that we did not hear the carriage until it was announced. I was about to take Fanny’s shawl to lay it round her shoulders when Crawford did it for me. I glanced at Mary and she smiled at me, wishing us a safe journey back to the Park. And now, back in my room, I feel the time is coming when I must put Mary’s feelings to the test, for I cannot hide my own any longer. I am in love with her, and I wish to make her my wife. Once Christmas is over and I have been ordained, I will be in a position to know exactly what I have to offer her.

But will it be enough? When I think of all the encouragements she has given me, the smiles and playful comments, the thoughts and feelings shared, then I think yes. But when I think of her comments on the necessity of wealth and her decided preference for London life, I am sure she will say no.

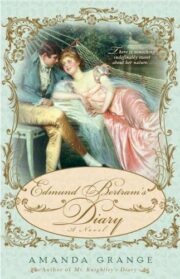

"Edmund Bertram’s Diary" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Edmund Bertram’s Diary". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Edmund Bertram’s Diary" друзьям в соцсетях.