‘—I was questioned, and received many severe reproaches: But I refused to confess who was my undoer; and for that obstinacy was turned from the castle.’

‘Be quick with your narrative, or you’ll break my heart,’ said Crawford, pressing her hand to his lips in a way I was sure was not in the script.

‘I will say something if you will not,’ I said to Tom.

‘Oh, very well, I suppose those lines could be cut. Maria!’ he called. ‘There is no need to say that about fervent caresses.’

‘But it is one of the most touching lines in the play!’ protested Crawford.

‘It shall not be said in this house,’ I replied, and carried my way.

‘Ah! Count!’ said Tom, as Rushworth entered the room. ‘Just the fellow I was looking for. Give me my line.’

‘Line? What line?’ said Rushworth.

‘The line that leads into my verses:

‘For ah! the very night before,

No prudent guard upon her,

The Count he gave her oaths a score,

And took in change her honor.’

‘You are out there, Bertram,’ said Rushworth. ‘That comes before the Count enters, and not afterwards.’

‘No, no, before the Count enters I say:

‘Then you, who now lead single lives,

From this sad tale beware;

And do not act as you were wives,

Before you really are.’

I found my script and left them to their arguing, glad to escape to the garden. It was refreshing to be outside, where I was not surrounded by fallen women, seducers and libertines. I got my part by heart, and though it was not perfectly learnt, at least it was learnt after a fashion.

I returned to the house, where I found my aunt still at work on the curtains.

‘And when you have finished there, you will oblige me by running across to my house and fetching my scissors,’ said my aunt to Fanny, as I entered the drawing-room.

‘Send someone else,’ I said. ‘I need Fanny.’

And so saying, I rescued her from her needlework and took her into the library, where we had a sensible conversation until dinner-time.

Even our meal could not be eaten in peace, for hardly had we all entered the dining-room than the others began reciting their parts.

‘I’ll not keep you in doubt a moment,’ boomed Yates, as we all sat down. ‘You are accused, young man, of being engaged to another woman while you offer marriage to my child.’

‘To only one other woman? ’ Rushworth replied.

‘What do you mean? ’ Yates declaimed.

‘My meaning is, that when a man is young and rich, has travelled, and is no personal object of disapprobation, to have made vows but to one woman is an absolute slight upon the rest of the sex.’

I was astonished at his remembering such a long speech, until I noticed he had a copy of the script hidden under the table.

‘Please, let us have no more until we have eaten our dinner, ’ I begged, as the soup was brought in, but I was talking to myself.

‘He talked of love, and promised me marriage,’ said Maria in sepulchral tones.

‘Why should I tremble thus?’ asked Crawford.

It was a very Bedlam.

Mary caught my eye and gave me an understanding smile. Then she said, ‘But we must forgive them, you know, the performance is now so very near. You and I must practice our scenes together tomorrow. We must have them right before we perform.’

I agreed, but only with a nod; for when I thought of the words I must say to her, and she to me, I found I could not speak.

Thursday 13 October

I rose early and went downstairs, where I found Christopher Jackson putting the finishing touches to the stage. It stretched from one end of the room to the other, and was set to rival the stage at Drury Lane.

‘Master Thomas’s orders,’ said Jackson, when I protested. ‘When I’ve finished with the stage, I’m to see about building the wings.’

I countermanded Tom’s orders and then, over breakfast, I finished learning my lines. I found I was dreading saying them to Mary, and so I repaired to Fanny’s sitting-room, there to gain courage by reading them through with her first. But when I tapped on the door and went in I found, to my surprise, that Mary was already there, bent on the same task. There was surprise; a little awkwardness; then I said, ‘As we are both here, we must rehearse together,’ for it seemed easier to think of reciting our parts if there was a third person present. She was at first reluctant but soon gave way to my entreaties. I handed my script to Fanny, begging her to help us, and to tell us when we went wrong.

Mary began nervously, for the part of Amelia was not an easy one for her: to pretend to be a young girl who was being persuaded into marrying a man she did not love by her father, when all the time her heart belonged to my character, a lowly clergyman.

‘Ah! good morning, my dear Sir; Mr. Anhalt, I meant to say; I beg pardon,’ said Mary to me.

‘Never mind, Miss Wildenhaim; I don’t dislike to hear you call me as you did,’ I said, rather stiffly.

‘In earnest?’ she asked, looking up at me.

‘Really,’ I said, more tenderly. ‘You have been crying. May I know the reason? The loss of your mother, still?’

‘No,’ she said, with a heartrending sigh. ‘I have left of crying for her.’

‘I beg pardon if I have come at an improper hour; but I wait upon you by the commands of your father.’

‘You are welcome at all hours,’ she said. ‘My father has more than once told me that he who forms my mind I should always consider as my greatest benefactor.’ She looked down shyly.

‘And my heart tells me the same.’

Was there more to her words than a performance of the play? Did she think I was the man who could form her mind? And did she want me to be that man? Did her heart tell her that it was so?

‘I think myself amply rewarded by the good opinion you have of me,’ I said, and to my surprise, I found myself wanting to take her hand.

‘When I remember what trouble I have sometimes given you, I cannot be too grateful,’ she said, with a speaking look.

I thought of the trouble she had given me, and thought how well our lives matched the play; and how strange it was that Tom should have chosen it; and that it was perhaps not such a bad thing that he had.

‘Oh! Heavens!’ I said.

Fanny said gently, ‘That bit is to yourself.’

‘Oh? Is it? Thank you, Fanny.’ I turned aside, and said the words as she directed.

‘I — I come from your father with a commission,’ I said. ‘If you please, we will sit down.’ I looked about me for a chair. I found one and Mary found another. We both sat down, I nervously, and Mary very elegantly, arranging her skirts gracefully about her. ‘Count Cassel is arrived.’

‘Yes, I know,’ she said.

‘And do you know for what reason?’

She looked at me with liquid eyes; eyes that were as transparent as the sunlight.

‘He wishes to marry me,’ she said.

I could not blame him. At that moment, I believe any man alive would have wished to marry her.

‘Does he?’ Fanny prompted me, when I did not speak.

‘Does he?’ I asked hastily. ‘But believe me, your father... the Baron will not persuade you. No, I am sure he will not.’

‘I know that,’ she said, with downcast eyes.

‘He wishes that I should ascertain whether you have an inclination—’

‘For the Count, or for matrimony do you mean?’

‘For matrimony,’ I said, finding myself growing hot, and, glancing at the grate, being surprised to see that there was no fire.

‘All things...’ whispered Fanny.

‘Thank you, Fanny,’ said Mary, then continued with her lines. ‘All things that I don’t know, and don’t understand, are quite indifferent to me.’

‘For that very reason I am sent to you to explain the good and the bad of which matrimony is composed.’

As I said it, I found my eyes meeting hers, and something passed between us.

‘Then... then I beg first to be acquainted with the good,’ she said.

‘When two sympathetic hearts...’ I swallowed. ‘When two sympathetic hearts meet in the marriage state, matrimony may be called a happy life. When such a wedded pair find thorns in their path, each will be eager, for the sake of the other, to tear them from the root. Where they have to mount hills, or wind a labyrinth, the most experienced will lead the way, and be a guide to his companion. Patience and love will accompany them in their journey, while melancholy and discord they leave far behind. Hand in hand they pass on from morning till evening, through their summer’s day, till the night of age draws on, and the sleep of death overtakes the one. The other, weeping and mourning, yet looks forward to the bright region where he shall meet his still surviving partner, among trees and flowers which themselves have planted, in fields of eternal verdure.’

She looked deep into my eyes and said, ‘You may tell my father — I’ll marry.’

She rose from her chair and I wondered if her look, her tone and her meaning could be for me. Would she marry me?

I wished there was no more to be said, but Fanny, faithful prompter that she was, reminded me of my next line.

‘This picture is pleasing,’ I said, ‘but I must beg you not to forget that there is another on the same subject. When convenience, and fair appearance joined to folly and ill-humor, forge the fetters of matrimony, they gall with their weight the married pair.’

‘Discontented...’ said Fanny.

‘Discontented with each other,’ I went on, ‘at variance in opinions — their mutual aversion increases with the years they live together. They contend most, where they should most unite; torment, where they should most soothe. In this rugged way, choked with the weeds of suspicion, jealousy, anger, and hatred, they take their daily journey, till one of these also sleep in death. The other then lifts up his dejected head, and calls out in acclamations of joy — Oh, liberty! dear liberty!’

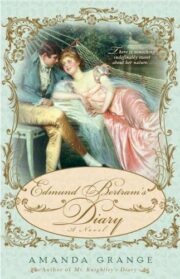

"Edmund Bertram’s Diary" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Edmund Bertram’s Diary". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Edmund Bertram’s Diary" друзьям в соцсетях.