‘You are lucky to have such a brother, but I am sure you deserve him. I have quite a curiosity to see him. I imagine him a very fine young man. If you will take my advice, Miss Price, you will get his picture drawn before he goes to sea again, it will be something good for you to keep by you.’

Such kindness could not help but provoke affectionate feelings from me, and, Miss Crawford happening to look up at that moment, her eyes met mine. We smiled. And then Tom called out, ‘I have just been looking at my part again, and can see no way of taking Anhalt as well as the Butler. I had thought, if I left out a few words here and there, I could make it do, but it is impossible. But there will not be the smallest difficulty in filling it. I could name at this moment at least six young men within six miles of us, who are wild to be admitted into our company, and there are one or two that would not disgrace us. I should not be afraid to trust Charles Maddox. I will take my horse early tomorrow morning and ride over to Stoke and settle with him.’

Miss Crawford was too well-mannered to make a complaint but she looked perturbed, and remarked to Fanny, ‘I am not very sanguine as to our play, and I can tell Mr. Maddox that I shall shorten some of his speeches, and a great many of my own, before we rehearse together.’

I felt all the wrongness of it, that a lovely young woman like Miss Crawford should be obliged to act such a part, and, even worse, to act it with a stranger. I began to feel that anything would be better than to leave her to such a fate, and to wonder whether I should agree to play the part of Anhalt, after all.

Tuesday 4 October

I could not sleep, and turned the idea of the play over and over in my mind as I lay awake in my bed. Was it best to resist every effort to persuade me to take part in the play and expose Miss Crawford to the indignity of acting with a man she did not know; especially in such a part, where the scenes were so warm; or should I save her from such a fate by taking the part myself? I was faced with a choice of two evils; and whilst it was the act of a responsible son to do the former, it was the act of a gentleman to do the latter.

I rose early, too restless to lie abed, and went out for a ride, but I was no nearer deciding what to do when I returned, and so I repaired to Fanny’s sitting-room at the top of the house. A tap on the door, a gentle ‘Come in,’ and I was inside the room, feeling better the moment I stepped over the threshold. The geraniums were still in bloom, their red heads looking bright and cheerful against the white windows, and the transparencies were glowing as the autumn sun shone through them, casting colored light on to the floor. And there was Fanny herself, the best sight of all, looking up from her book with her welcoming smile.

‘Can I speak with you, Fanny, for a few minutes?’ I asked.

‘Yes, certainly.’

‘I want to consult. I want your opinion.’

‘My opinion?’ she asked in surprise.

‘I do not know what to do.’

I sat down and then stood up again, walking about the room as I laid the matter before her.

‘I know no harm of Charles Maddox; but the excessive intimacy which must spring from his being admitted among us in this manner is highly objectionable, the more than intimacy — the familiarity. I cannot think of it with any patience; and it does appear to me an evil of such magnitude as must, if possible, be prevented. Do not you see it in the same light?’

‘Yes; but what can be done? Your brother is so determined. ’

‘There is but one thing to be done, Fanny. I must take Anhalt myself. I am well aware that nothing else will quiet Tom.’

Fanny did not answer me. I knew exactly what she was feeling, for I was feeling it myself.

‘After being known to oppose the scheme from the beginning, there is absurdity in the face of my joining them now, when they are exceeding their first plan in every respect,’ I said, ‘but I can think of no other alternative. Can you, Fanny?’

‘No,’ she admitted. ‘I am sorry for Miss Crawford. But I am more sorry to see you drawn in to do what you had resolved against.’

I did not like it myself, but I felt it must be.

‘As I am now, I have no influence, I can do nothing,’ I said. ‘I have offended them, and they will not hear me; but when I have put them in good-humor by this concession, I am not without hopes of persuading them to confine the representation within a much smaller circle than they are now in the high road for.’

I could tell she did not like it.

‘Give me your approbation, Fanny. I am not comfortable without it. If you are against me, I ought to distrust myself — and yet — but it is impossible to let Tom go on in this way, riding about the country in quest of anybody who can be persuaded to act. I thought you would have entered more into Miss Crawford’s feelings. She never appeared more amiable than in her behavior to you last night. It gave her a very strong claim on my goodwill.’

‘She was very kind, indeed, and I am glad to have her spared,’ said Fanny.

‘I knew you would think so,’ I said, much relieved to find she thought as I did. ‘And now, dear Fanny, I will not interrupt you any longer. You want to be reading. But I could not be easy till I had spoken to you, and come to a decision. Sleeping or waking, my head has been full of this matter all night. It is an evil, but I am certainly making it less than it might be. If Tom is up, I shall go to him directly and get it over, and when we meet at breakfast we shall be all in high good humor at the prospect of acting the fool together with such unanimity.’

I left her to her books and went down to breakfast, where I had the unpleasant task of telling Tom and Maria that I would take the part of Anhalt after all. They did not crow too loud, and, as I had hoped, were so pleased at my actions, that they agreed to limit the audience to Mrs. Rushworth and the Grants.

After breakfast I walked down to the Parsonage and gave the news there as well. Miss Crawford’s smiles rewarded me for my troubles and I felt that, after all, I had done the best I could in a difficult situation.

There was one other consolation. Miss Crawford, in the goodness of her heart, persuaded her sister to take the part of Cottager’s Wife, so that Fanny would not be entreated to perform again. My joy was short-lived, for when I returned to the Park I found Maria and Crawford rehearsing their parts so avidly I thought they could not forget their lines if they lived to be ninety. Every time I came upon them, Maria was either embracing Crawford or laying her head on his breast, so that I began to think I should have forbidden the play, sent Yates about his business, and locked Maria in her room until my father returned.

Wednesday 5 October

The house was in chaos this morning. I could not move without falling over someone. If it was not Tom, prancing around and saying:

‘There lived a lady in this land,

Whose charms the heart made tingle;

At church she had not given her hand,

And therefore still was single.’

it was Yates, telling Julia she should not have been allowed to sit out, but should have been persuaded to take the part of Amelia, which would have suited her talents admirably; or my aunt, telling us she had managed to save half a crown here and half a crown there; or Rushworth, attempting to learn his forty-two speeches and failing miserably to learn even one. Fanny was dragooned by my aunt, who, seeing her with a moment to herself between prompting Rushworth and condoling with Tom over the shortcomings of the scene painter, said,

‘Come, Fanny, these are fine times for you, but you must not be always walking from one room to the other, and doing the lookings-on at your ease, in this way; I want you here. I have been slaving myself till I can hardly stand, to contrive Mr. Rushworth’s cloak without sending for any more satin; and now I think you may give me your help in putting it together. There are but three seams; you may do them in a trice. It would be lucky for me if I had nothing but the executive part to do. You are best off, I can tell you: but if nobody did more than you, we should not get on very fast.’

I was about to speak up for Fanny when Mama pleased me greatly by saying, ‘One cannot wonder, sister, that Fanny should be delighted: it is all new to her, you know.’

I blessed her silently and went into the billiard room to find my script, for I had a great deal to learn.

As soon as I entered I heard Maria and Crawford rehearsing their lines. Maria said, in languishing tones: ‘He talked of love, and promised me marriage. He was the first man who ever spoke to me on such a subject. His flattery made me vain, and his repeated vows — Oh! oh! I was intoxicated by the fervent caresses of a young, inexperienced, capricious man, and did not recover from the delirium till it was too late.’

I was horrified. Fervent caresses! Delirium! And Tom was standing there, listening to them from the side of the room, and encouraging them!

‘Tom, I thought those lines had been cut,’ I said.

‘Why should they be cut?’ he asked, whilst singing under his breath all the while:

‘Count Cassel wooed this maid so rare,

And in her eye found grace;

And if his purpose was not fair,

It probably was base.’

‘They are far too warm,’ I said.

‘Too warm? Nonsense.’

Maria, meanwhile, was declaiming: ‘His leave of absence expired, he returned to his regiment, depending on my promise, and well assured of my esteem. As soon as my situation became known—’

‘Her situation!’ I exploded.

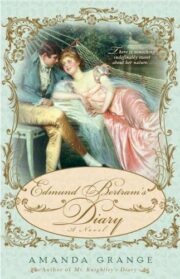

"Edmund Bertram’s Diary" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Edmund Bertram’s Diary". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Edmund Bertram’s Diary" друзьям в соцсетях.