I thought her pride would sway her, for she looked as though she was about to give way, but then her face closed and she said, ‘I am much obliged to you, Edmund; you mean very well, I am sure: but I still think you see things too strongly; and I really cannot undertake to harangue all the rest upon a subject of this kind. There would be the greatest indecorum, I think.’

‘Do not act anything improper, my dear,’ said Mama, overhearing a part of our conversation, and rousing herself momentarily. ‘Sir Thomas would not like it.’ But her concern was short-lived, for a moment later she was saying, ‘Fanny, ring the bell; I must have my dinner.’

‘I am convinced, madam,’ I said to my mother, pressing what small advantage I had gained from her contribution to the conversation, ‘that Sir Thomas would not like it.’

‘There, my dear, do you hear what Edmund says?’ said Mama to Maria.

‘If I were to decline the part,’ said Maria, ‘Julia would certainly take it.’

‘Not if she knew your reasons!’ I said.

‘Oh! she might think the difference between us — the difference in our situations — that she need not be so scrupulous as I might feel necessary. I am sure she would argue so. No; you must excuse me; I cannot retract my consent; it is too far settled, everybody would be so disappointed, Tom would be quite angry; and if we are so very nice, we shall never act anything.’

‘I was just going to say the very same thing,’ said my aunt. ‘If every play is to be objected to, you will act nothing, and the preparations will be all so much money thrown away, and I am sure that would be a discredit to us all. I do not know the play; but, as Maria says, if there is anything a little too warm (and it is so with most of them) it can be easily left out. We must not be over precise, Edmund. As Mr. Rushworth is to act too, there can be no harm. I only wish Tom had known his own mind when the carpenters began, for there was the loss of half a day’s work about those side-doors. The curtain will be a good job, however. The maids do their work very well, and I think we shall be able to send back some dozens of the rings. There is no occasion to put them so very close together. I am of some use, I hope, in preventing waste and making the most of things.’

And off she went, delighted at having saved the estate half a crown by her careful use of curtain rings, when she had cost it pounds by her excessive use of baize. Dinner passed heavily. The only thing that heartened me was the discovery that Julia had refused to act.

As soon as we returned to the drawing-room, discussion of the play began again. Whilst the others were engaged, I took the opportunity of drawing Tom to one side.

‘I cannot believe you mean to perform Lovers’ Vows,’ I said to him.

‘Why ever not?’ he said. ‘There is nothing wrong with it.’

‘Nothing wrong with having Maria act out the part of a woman who is seduced and left with an illegitimate child? Especially situated as she is, in a long engagement with Rushworth—’

‘And you think it will give him ideas? You need not have any fear that he will seduce her. I doubt if he has it in him,’ said Tom.

‘I wish you would be serious, Tom.’

‘I am perfectly serious.’

‘Very well then, what will Rushworth think of seeing his fiancée perform the speeches and acquire the mannerisms of such a woman?’

‘He will not pull back, if that is what you are worried about. Listen to him! He is too busy thinking about his pink satin cloak to notice what Maria does. I verily believe it has taken the place of his dogs in his affections, for I have not heard him mention the animals once all day.’

‘If Julia knows it is wrong, and has refused to act—’

Tom laughed. ‘The only reason she refused to act is that she wanted the part of Agatha, and once it went to Maria she refused to take any other. It was ill-humor, and not scruples, that prevented her taking part.’

I was dismayed. I felt I had let my father down. He had entrusted his daughters to my care, and what had become of them? Had they turned into the young women he would like them to be?

No, they had turned into creatures who fought over the dubious pleasure of portraying a fallen woman.

‘Besides, Miss Crawford has agreed to it, so how can it be wrong?’ continued Tom.

‘She is a very obliging woman who would agree to anything if it would increase the pleasure of others,’ I said.

But he only laughed and went off to join the others, saying, ‘We must have three scene changes. No, four....’

I retired to the side of the room, where I sat beside Mama and listened to her tales of Pug. By and by, I walked over to the table, where I saw a copy of Lovers’ Vows lying open. I picked it up, hoping I might have misremembered it, but my fears increased as soon as I opened it and read what was written there.

Agatha. I cannot speak, dear son! [Rising and embracing him ] My dear Frederick! The joy is too great... I was not prepared...

Frederick. Dear mother, compose yourself: [leans her against his breast] now, then, be comforted. How she trembles! She is fainting.

I could not think of Maria embracing Crawford, or he leaning her against his breast, without fearing for my sister’s reputation; to say nothing of her future, for her eagerness to play such a part left me with the disquieting belief that her feelings for Rushworth were far from fixed. My only consolation was that the performance was to be a private one, and that no one beyond our family circle would ever know of it.

I put the book down and returned to Mama, who had been joined by Fanny.

‘This is a bad business, Fanny,’ I said.

She shared my feelings, and it was a relief to me to be able to talk of them with someone who felt the same.

We were soon joined by the Crawfords, who had walked over from the Parsonage. Miss Crawford, ever solicitous for the feelings of others, spoke at once to Mama.

‘I must really congratulate your ladyship,’ said she, ‘on the play being chosen; for though you have borne it with exemplary patience, I am sure you must be sick of all our noise and difficulties. The actors may be glad, but the bystanders must be infinitely more thankful for a decision; and I do sincerely give you joy, madam, as well as Mrs. Norris, and everybody else who is in the same predicament,’ she said, glancing towards Fanny and me.

‘I am glad it is settled on at last,’ said Mama.

Miss Crawford joined the others, but I could tell she had no real taste for the endeavor, and who could blame her, being asked to play the part of such a pert, forward young woman as Amelia?

I could tell there was something on her mind and at last it came out when she asked, ‘Who is to play Anhalt?’

‘I should be but too happy in taking the part, if it were possible,’ cried Tom; ‘but, unluckily, the Butler and Anhalt are in together. I will not entirely give it up, however; I will try what can be done — I will look it over again.’

Yates suggested I do it, but I could not in all conscience take the part, for that would be to condone the folly. My father left his daughters and his estate in my care, and I have no intention of handing them back to him ruined when he returns in two months’ time. Miss Crawford soon left the others and joined Fanny and me.

‘They do not want me at all,’ said she, seating herself. ‘Mr. Edmund Bertram, as you do not act yourself, you will be a disinterested adviser; and, therefore, I apply to you. What shall we do for an Anhalt? Is it practicable for any of the others to double it? What is your advice?’

‘My advice is that you change the play,’ I said.

‘I should have no objection, for though I should not particularly dislike the part of Amelia if well supported, that is, if everything went well, I shall be sorry to be an inconvenience; but as they do not choose to hear your advice at that table, it certainly will not be taken.’ She fell silent for a moment and then said, ‘If any part could tempt you to act, I suppose it would be Anhalt, for he is a clergyman, you know.’

‘That circumstance would by no means tempt me,’ I said ungraciously, remembering how she had ridiculed my calling. ‘It must be very difficult to keep Anhalt from appearing a formal, solemn lecturer; and the man who chooses the profession itself is, perhaps, one of the last who would wish to represent it on the stage.’

She fell silent and then moved her chair away.

I was instantly sorry for my ill-humor, and feared I had not been polite. Besides, I could not help wondering if her words had been meant as an olive branch. By asking me to play Anhalt, was she not telling me that she no longer found the clergy objectionable?

I was about to speak to her when Tom began to urge Fanny to take the part of Cottager’s wife.

‘Me!’ cried Fanny, with a most frightened look. ‘Indeed you must excuse me. I could not act anything if you were to give me the world. No, indeed, I cannot act.’

This provoked such an unkind torrent of words from my aunt, saying that Fanny was ungrateful and other such nonsense, that I would have spoken, except that I was for the moment too angry to do so. But I found there was no need, for Miss Crawford glanced at her brother to prevent any further urging from the actors and then pulled her chair close to Fanny’s so that she could comfort her in the most charming way.

‘You work very neatly,’ she said, looking at Fanny’s needlework. ‘I wish I could work as well. And it is an excellent pattern. You would oblige me very much if you would lend it to me.’

Fanny’s tears were blinked back from her eyes and soon turned to smiles when Miss Crawford asked about William.

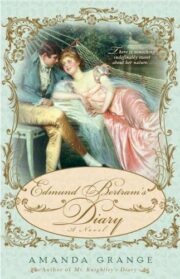

"Edmund Bertram’s Diary" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Edmund Bertram’s Diary". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Edmund Bertram’s Diary" друзьям в соцсетях.