‘Perhaps I have,’ she returned, and I knew that, in her imagination, she was seeing the Abbey Scott had described, in the eerie light of moonlight. She began to murmur:

‘The darken’d roof rose high aloof

On pillars lofty and light and small;

The key-stone, that lock’d each ribbed aisle,

Was a fleur-de-lys, or a quatre-geuille,

The corbel s were carved grotesque and grim;

And the pillars, with cluster’d shafts so trim,

With base and with capital flourish’d around,

Seem’d bundles of lances which garlands had bound.’

I continued:

‘Full many a scutcheon and banner riven,

Shook to the cold night-wind of heaven,

Around the screenëd altar’s pale;

And there the dying lamps did burn,

Before thy low and lonely urn,

O gallant Chief of Otterburne.’

‘But here are no pillars, no lamps, no inscriptions,’ she said, disappointed.

‘You forget, Fanny, how lately all this has been built, and for how confined a purpose, compared with the old chapels of castles and monasteries. It was only for the private use of the family. They have been buried, I suppose, in the parish church. There you must look for the banners and the achievements.’

‘It was foolish of me not to think of all that; but I am disappointed all the same. I hoped to find banners being blown by the night wind of heaven. Or even,’ she added with a smile, ‘rustling with the current of air, foretelling woe and destruction.’

‘Now that I know,’ said Miss Crawford. ‘It is from Charlotte Smith’s The Old Manor House.’

‘You have read it?’ I asked.

‘Indeed, I am fond of Gothic romances — particularly on long winter evenings when there is nothing better to do. Henry read it to me last year. And to be sure, this chapel needs a current of air foretelling woe, for it is very dull.’

Mrs. Rushworth, ahead with the others, was explaining that, although the house had its own chapel, it was no longer used for family prayers.

‘Every generation has its improvements,’ said Miss Crawford in a droll voice. And, just as I felt I was getting to know her, I realized I did not know her at all. I was dismayed by her attitude, for I have always felt there was something fine about a family assembling for prayers, all together, turning their thoughts into the same path before they separate for the day.

Fanny voiced my thoughts, but Miss Crawford was not to be persuaded, saying satirically, ‘Very fine indeed! It must do the heads of the family a great deal of good to force all the poor housemaids and footmen to leave business and pleasure, and say their prayers here twice a day, while they are inventing excuses themselves for staying away.’

‘That is hardly Fanny’s idea of a family assembling,’ I told her. But she would not be serious, saying, ‘Cannot you imagine with what unwilling feelings the former belles of the house of Rushworth did many a time repair to this chapel? The young Mrs. Eleanors and Mrs. Bridgets — starched up into seeming piety, but with heads full of something very different — especially if the poor chaplain were not worth looking at — and, in those days, I fancy parsons were very inferior even to what they are now.’

Fanny colored, for she felt all the unluckiness of this remark as it reflected on my chosen profession. But although I was dismayed at Miss Crawford’s attitude, I took heart from the fact that she was surely capable of thinking seriously on serious subjects if only she was given encouragement to do so. She could not have reached womanhood without realizing that not everything in life could be turned into a jest.

I was hoping to discuss it with her, but barely had we begun when Julia distracted our attention by saying, ‘Do look at Mr. Rushworth and Maria, standing side by side, exactly as if the ceremony were going to be performed. Have not they completely the air of it? Upon my word, it is really a pity that it should not take place directly, if we had but a proper license, for here we are altogether, and nothing in the world could be more snug and pleasant.’

‘It will be a most happy event to me, whenever it takes place,’ said Mrs. Rushworth.

‘My dear Edmund, if you were but in orders now, you might perform the ceremony directly. How unlucky that you are not yet ordained. Mr. Rushworth and Maria are quite ready.’

Miss Crawford looked stunned.

‘Ordained!’ she said, turning to me and looking aghast. ‘What, are you to be a clergyman?’

‘Yes, I shall take orders soon after my father’s return — probably at Christmas,’ I told her. She regained her color quickly, saying, ‘If I had known this before, I would have spoken of the cloth with more respect.’

I smiled, for it showed that, as I suspected, she had a good heart, and had simply been carried away by playfulness. As we left the chapel I walked beside her to show I was not offended by her unfortunate remarks.

We soon afterwards came to a door leading outside. We took it, and found ourselves amidst lawns and shrubs, where pheasants roamed at will. There was also a bowling-green and a long terrace walk, backed by iron palisades, beyond which lay a wilderness. Crawford spotted the capabilities of the area and was soon deep in conversation with Maria and Rushworth, whilst Fanny, Miss Crawford and I went on. The day was hot and after a walk along the terrace, Miss Crawford expressed a wish to go into the wilderness, where we would be cool beneath the trees. We went in, going down a long flight of steps, and found ourselves in darkness and shade.

‘This is better,’ said Miss Crawford. ‘Give me a wilderness and I am happy, rather than a straight path which is hard beneath the feet. Here is nature untrammeled, not bent into shapes which do not suit her, but allowed to roam free. It is a much happier place. Do you not think so, Mr. Bertram?’

‘For my own part I prefer a path, but the wilderness has a certain allure,’ I conceded.

‘There is too much regularity in the planting, but otherwise a pretty wilderness, very pretty indeed,’ said Miss Crawford.

‘Too much regularity! Not at all,’ said Fanny. ‘Nature must have some order, or we would lose our way.’

Miss Crawford was soon speaking again of my plans to become a clergyman.

‘Why should it surprise you?’ I asked her. ‘You must suppose me designed for some profession, and might perceive that I am neither a lawyer, nor a soldier, nor a sailor.’

‘Very true; but, in short, it had not occurred to me. And you know there is generally an uncle or a grandfather to leave a fortune to the second son.’

‘A very praiseworthy practice, but not quite universal!’

‘But why are you to be a clergyman?’ she said, puzzling over it. ‘I thought that was always the lot of the youngest, where there were many to choose before him.’

‘Do you think the church itself never chosen?’ I asked, amused at her ignorance.

‘Men love to distinguish themselves, and a clergyman is nothing.’

I was only too happy to prove her wrong, and Fanny ventured her own opinions, which were in support of mine.

‘You have quite convinced Miss Price already,’ said Miss Crawford satirically.

‘I wish I could convince Miss Crawford, too,’ I returned.

She laughed and said, ‘I do not think you ever will. You really are fit for something better. Come, do change your mind. It is not too late. Go into the law,’ she offered.

‘Go into the law! With as much ease as I was told to go into this wilderness!’ I said, torn between exasperation and amusement.

‘Now you are going to say something about the law being the worst wilderness of the two,’ she said with an arch smile, ‘but I forestall you.’

‘You need not hurry when the object is to prevent me from saying a bon mot, for there is not the least wit in my nature, ’ I said, for I was frustrated by her determination to turn everything into a joke.

A general silence fell, and I regretted my ill-humored words, but they were said and could not be recalled. It was broken only when Fanny said she was tired and that, when we came to a seat, she would like to rest for a while.

I immediately drew her arm through mine, to give her my support, and after a moment’s hesitation I offered my other arm to Miss Crawford. To my relief she took it and we walked on. The gloom did not last long, and I blessed Miss Crawford’s wit and good humor just as much as, a few minutes before, I had been condemning them, for she bore no grudge for my sharpness and was soon teasing me again.

‘We have walked a very great distance,’ she said airily. ‘It must have been at least a mile.’

‘Not half a mile!’ I protested.

‘Oh! you do not consider how much we have wound about. We have taken such a very serpentine course, and the wood itself must be half a mile long in a straight line, for we have never seen the end of it yet since we left the first great path.’

‘But if you remember, before we left that first great path, we saw directly to the end of it. We looked down the whole vista, and saw it closed by iron gates, and it could not have been more than a furlong in length.’

‘Oh! I know nothing of your furlongs,’ she said, ‘but I am sure it is a very long wood.’

‘We have been exactly a quarter of an hour here,’ I teased her, taking out my watch. ‘Do you think we are walking four miles an hour?’

‘Oh! do not attack me with your watch. A watch is always too fast or too slow. I cannot be dictated to by a watch!’

Perfect good humor was restored by the time we came to the bottom of the wood, where there was a seat, and we all sat down.

‘To sit in the shade on a fine day, and look upon verdure, is the most perfect refreshment,’ said Fanny.

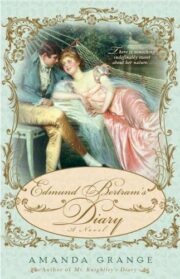

"Edmund Bertram’s Diary" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Edmund Bertram’s Diary". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Edmund Bertram’s Diary" друзьям в соцсетях.