They expected her to come home rested and happy after a week’s cosseting in her old home, but when she finally returned she was tired and pale. The city had been unbearably hot, she said. There were more beggars on the streets than ever; she had seen a man dying in the gutter and had feared to touch him in case he was carrying the plague.

“What sort of country is this, that the act of a good Samaritan is too dangerous to do?” she demanded, genuinely grieved at the struggle between her conscience and her safety.

Her father and all the merchants were complaining that they were taxed for trading, and then taxed for selling, and then taxed for storing goods. They too were ordered to pay ship money, which was set by an assessor who would come around and guess how much you were worth by the appearance of your house and business, and there was no appeal against him.

Josiah Hurte had to stand the charge of paying for his own lecturer in his own chapel, and also had to pay his parish dues to a church he never entered, and tithes to a vicar he despised for Roman practices. Meanwhile the price of goods soared; there were pirates openly operating up and down the English Channel; there were rumors of a rebellion in Ireland; and the king was said to spend more on his collection of pictures than he did on the Navy.

Jane, as the wife and daughter-in-law of a man in the employ of the court, had been pestered for scandalous details and had suffered from association. “Nothing good will come from this king,” her father had said. “You may think your husband is high in his favor but nothing good can come from him because he is a king halfway to damnation already. And if you do not beware, he will drag you all down with him. Now that your father-in-law and husband have a fair house in Lambeth, why can they not bide there?”

Useless to try to explain to Josiah that if this king issued a command you could be hanged for treason if you said “no.” “The king himself ordered it,” Jane said. “How could we refuse?”

“By simply refusing,” her father said stoutly.

“And do you refuse to pay your taxes? Do you refuse to pay ship money? Other men do.”

“And they lie in prison,” Josiah said. “And shame the rest of us who are less staunch. No, I do as I am ordered.”

“And so does my husband,” Jane insisted, defending the Tradescants despite herself. “The king and court take our skills and ser-vice just as they take your money. This king takes whatever he desires and nothing can stop him.”

“You must be glad to be home,” J said in bed that night. He put his arm around her and she rested her head against his shoulder.

“I’m so tired,” she said fretfully.

“Then rest,” he said. He turned her face toward him and kissed her lips but she moved away.

“The room stinks of honeysuckle,” she cried suddenly. “You’ve brought cuttings into the bedroom again, John! I won’t have it.”

“No,” he said. He could feel a small niggle of fear, as small as a seedling, in his heart. “There’s nothing in the room. Does the air smell sweet to you, Jane?”

She suddenly realized what she had said, and what he was thinking, and she clapped her hand over her mouth as if she would hide her words and stop her breath from reaching him. “Oh God, no,” she said. “Not that.”

“Was it in the city?” John asked urgently.

“It’s always in the city,” she said bitterly. “But I spoke to no one knowingly.”

“Not the servants, not the apprentice boys?”

“Would I take the risk? Would I have come home if I had thought I was carrying it?”

She was half out of bed, throwing back the covers and throwing open the window, her hand still cupped over her mouth as if she did not want the smallest breath to escape. John reached out for her but did not pull her to him. His fear of the illness was as great as his love for her. “Jane! Where are you going?”

“I’ll get them to make me up a bed in the new orangery,” she said. “And you must put my food and water at the door, and not come near me. The children are to be kept away. And my bedding is to be burned when it is dirty. And burn candles around the door.”

He would have held her but she turned on him with a face of such fury that he recoiled. “Get away from me!” she screamed at him. “D’you think I want to give it to you? D’you think I want to tear down this house which has been the joy of my life to build up?”

“No…,” John stammered. “But Jane, I love you, I want to hold you…”

“If I survive,” she promised, her face softening, “then we will spend weeks in each other’s arms. I swear it, John. I love you. But if I die you are not even to touch me. You are to order them to bolt down the coffin and not even to look at me.”

“I can’t bear it!” he cried suddenly. “This can’t happen to us!”

Jane opened the door and called down the stairs. “Sally! Make up a bed for me in the orangery, and put all my clothes in there.”

“If I take it, I will join you,” John said. “And we will be together then.”

She turned her determined face to him. “You will not take it,” she said passionately. “You will live to care for Baby John, and for Frances, and for the trees and the gardens. Even if I die there is still Baby John to carry your name, and the trees and the gardens.”

“Jane-” It was a low cry, like a hurt animal’s.

She did not soften for a moment. “Keep my children from me,” she ordered harshly. “If you love me at all. Keep them from me.”

And she turned, gathered up all the clothes she had brought from the city, went down the stairs into the new-built orangery, lay down on the pallet bed which the maid had thrown on the floor and looked up to where the warm summer moonlight poured in the little window in the wooden wall, and wondered if she would die.

On the fourth day Jane found swollen lumps under her arms, and she could not remember where she was. She had a lucid interval at midday and when John came to speak to her from the doorway, behind the wall of candle flame, she told him to put a lock on the door so that she could not come out looking for Baby John, when she was out of her mind with the fever.

On the fifth day a message came from her mother to say that one of the apprentices had taken the plague and that Jane should burn everything she had worn or brought from her visit. They sent back the messenger with the news that the warning came too late, that already there was a white cross on the front door, and a warden standing outside to make sure that no one left the house to spread the plague in Lambeth. All the goods and groceries, and even the new rarities, were left on the little bridge which led from the road to the house, and all the money was left in a bowl of vinegar, to wash the coins clean. No one would go near the Tradescants’ door until they were all recovered or dead. The parish wardens were legally bound to make sure that any plague victims were isolated in their houses until they were proven to be dead or proven to be clean, and no one – not even the Tradescants with their fine business and their royal connections – could escape the ruling.

On the sixth day of her illness Jane did not tap on the door to have it unlocked in the morning. When John opened it and looked in, she was lying on the bed, her hair tumbled all over her pillow, her face thin and ghastly. When she saw him peering in she tried to smile, but her lips were too cracked and sore from fever.

“Pray for me,” she said. “And don’t take the plague, John. Keep Baby John safe. Is he still well?”

“He’s well,” John said. He did not tell her that her little son was crying and crying for her.

“And Frances?”

“No signs of it.”

“And you, and Father?”

“No one in the house seems to have it. But they have it in Lambeth. We’re not the only house with a white cross on the door. It’s going to be a bad year, this year.”

“Did I bring it?” she asked painfully. “Did I bring the plague to Lambeth? Did it follow me over the river?”

“It was here before you came home,” he reassured her. “Don’t blame yourself for it. Someone had it and tried to conceal it. It has been here for weeks and no one knew.”

“God help them,” she whispered. “God help me. Bury me deep, John. And pray for my soul.”

Impulsively, he stepped over the candles and came into the room. At once she reared up in her bed. “Do you want me to die in despair?” she demanded.

He checked and walked backward, as if she were the queen herself. “I want to hold you,” he said pitifully. “I want to hold you, Jane, I want to hold you to my heart.”

For a moment her gaunt strained face, lit by the dozen golden candle flames, was suddenly soft and young, as it had been when she had sold him inch after inch of ribbons in the mercer’s shop and he had called again and again on one pretext after another.

“Hold me in your heart,” she whispered. “And care for my children.”

She lay back on the pillows as John stepped over the wall of candle flames and hunkered down on the threshold.

“I shall stay here,” he said determinedly.

“All right,” she agreed. “Have you a pomander?”

“A pomander, and I am sitting in a sea of strewing herbs,” John said.

“Stay then,” she said. “I don’t want to die alone. But if I am feverish and wandering and start to come to you, you must slam the door in my face and lock it.”

He looked at her through the haze of the heat of the candles, and his face was nearly as haggard as her own. “I can’t do that,” he said. “I won’t be able to do that.”

“Promise me,” she demanded. “It’s the last thing I will ever ask of you.”

He closed his eyes for a moment, to find his resolution. “I promise,” he said eventually. “I will not touch you, I will come no closer. But I will be here for you. Just outside the door.”

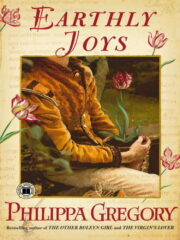

"Earthly Joys" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Earthly Joys". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Earthly Joys" друзьям в соцсетях.