“And what shall we do if the law changes?” Elizabeth asked. “This is a king who is changing the shape of the church itself, whose father changed the Bible itself. What if he changes yet more and makes us outlaws in our own church?”

J glanced at his mother. “That’s the very question,” he said. “I can bend for the moment, but what if matters get worse?”

“Practice before principle,” John said with Cecil’s old remembered wisdom. “We’ll worry about that if it happens. In the meantime we have a road we can all take together. We can obey the king and dig his wife’s garden, and keep our consciences to ourselves.”

“I will not listen to heresy and I will not bow down low to the papist queen,” J stated. “But I can be courteous to her and I can work for my father. Two wages coming in is better than one. And besides-” He glanced up at his father with a silent appeal. “I want to do my duty by you, Father. I want there always to be a Tradescant at Lambeth. I want things working right in their right places. It’s because the king does not work right in his right place that everything is so disturbed. I want order – just as you do.”

John smiled his warm loving smile at his son. “I shall make a Cecil of you yet,” he said gently. “Let us put some order in the queen’s garden and keep the steady order of our own lives, and pray that the king does his duty as we do ours.”

The queen had commanded that John should have lodgings in the park at Oatlands and that everything should be done as he wished. His house adjoined the silkworm house and was warmed by the sun all day and by the charcoal burners which were set about the walls of the silkworm house all night. John at first found the thought of his neighbors the maggots, silently munching their way through mulberry leaves night and day, immensely distasteful; but the house itself was a miracle of prettiness, a little turreted play-castle of wood, south-facing with mullioned windows and furnished by the order of the queen with pretty light tables, chairs and a bed.

He was to eat in the great hall with the other members of the household. The king demanded that dinner be served in the great hall in full state whether he was there or not. The ritual demanded that a cover be set on the table before his chair, that dishes be put before the empty throne and that every man should bow to the throne before entering the hall and on leaving it.

“This is superstition,” John exclaimed unwarily when he saw the men bowing low to the empty chair.

“It is how the king orders it,” one of the grooms of the bedchamber replied. “To maintain the dignity of the throne. It’s how it was done in Queen Elizabeth’s time.”

John shook his head. “Well, I remember Elizabeth’s time, which is more than most do,” he said. “Men bowed to her chair when she was going to sit on it, and bowed to her dinner when she was going to eat it. She was too parsimonious to have dinner served in ten palaces when she was only going to eat in one.”

The man shook his head, warning John to be silent. “Well, this is how it’s done now,” he said. “The king himself ordered it.”

“And when does he come?”

“Next week,” the groom said. “And then you will see a change. The place is only half-alive when Their Majesties are not here.”

He was right. Oatlands Palace was like a village with the plague when the court was elsewhere, the passages between one building and another empty and silent, half the kitchens cold, their fires unlit. But early in September a trail of carts and wagons came down the road from Weybridge, and a hundred barges rowed upstream from London bringing the king’s goods as the court moved to Oatlands for the month.

The palace was under siege from an army of shouting, arguing, ordering, singing cooks, maids, horsemen, grooms, servers and minor gentry of the household. Everyone had an urgent task and an important responsibility, and everyone got in everyone else’s way. There were tapestries to hang and pictures to place and floors to sweep and carpets to lay. All the king’s most beautiful furniture traveled with him; and his bedroom and the queen’s bedroom had to be prepared and perfect. The chimneys had to be swept before fires could be lit, but fires had to be lit to air the damp linen at once. The whole village, spread over nine acres, was in a state of complete madness. Even the deerhounds in the kennels caught the excitement and bayed all night long under the yellow September moon.

Tradescant broke the rule of dining in the great hall and went to Weybridge village to buy bread, cheese and small ale, which he took home to his little house in the gardens. He and the silkworms munched their way through their dinners in their adjoining houses. “Goodnight, maggots,” Tradescant called cheerfully as he blew his candle out and the deep country darkness enveloped his bedroom.

John had given no thought to meeting the king. When he had last seen His Majesty, they had both been waiting for Buckingham to come to Portsmouth. The time before that had been at the sailing of the first expedition to Rhé. When John was led into the king’s state bedchamber he found, with the familiar pang of sorrow, that he was looking around for his master. He could not believe that his duke was not there.

At once, like a ghost summoned by desire, he saw him. It was a life-size portrait of Buckingham painted in dark rich oils. One hand was outstretched as if to show the length and grace of the fingers and the wealth of the single diamond ring, the other hand rested on the rich pommel of his sword. His beard was neatly trimmed, his clothes were bright and richly embroidered and encrusted, but it was his face that drew Tradescant’s look. It was his lord, it was his lost lord. The thick dark hair, the arrogant laughing half-raised brows set over dark eyes, the irresistible smile, the sparkle, and that hint of spirituality, of saintliness, which King James had seen even as he had loved the sensual beauty of the face.

John thought how he still touched his lord in his mind, almost every morning and every night, and how he had thought that perhaps the king too reached out over death to his friend. But now he saw that the king had a greater comfort, for every night and every morning he could glance at that assured smiling face and feel the warmth of those eyes, and if he wished he could touch the frame of the picture, or even brush a kiss upon the painted cheek.

The portrait was new in the chamber, along with the rich curtains and the thick Turkey rugs on the floor. The king’s most precious goods traveled with him everywhere he went. And the king’s most precious thing was the portrait which hung, wherever he slept, at his bedside where he could see it before closing his eyes at night and on waking in the morning.

Charles came silently into his bedchamber from his private adjoining room and hesitated when he saw John looking up at the portrait. Something in the tilt of the man’s head and the steadiness of his look reminded the king that John too had lost a man who had been at the very center of his world.

“Y… you are looking at my p… portrait of the… duke.”

John turned, saw the king and dropped to his knees, flinching a little as his bad knee hit the floor.

The king did not command him to rise. “Your l… late master.” His voice still held traces of the paralyzing stammer he had suffered from as a child. Only with his intimates could he speak without hesitation; only with two people, the duke and now his wife, had he ever been fluent.

“You m… must miss him,” the king went on. It sounded more like an order than an offer of sympathy.

John looked up and saw the king’s face. Grief had changed him; he looked older and more tired, and his brown hair was thinning.

His eyes were heavily lidded, as if he were weary of what he saw, as if he no longer expected to see what he wanted.

“I grieve for him still,” John said honestly. “Every day.”

“You l… loved him?”

“With all my heart,” John replied.

“And he l… loved you?”

John looked up at his king. There was passion behind the question. Even after his death Buckingham could still inspire jealousy. John, the older man, smiled wryly. “He loved me a little,” he said. “When I served him especially well. But one smile from him was worth a piece of gold from another.”

There was a silence. Charles nodded as if the statement was of little consequence and turned away to the window and looked out into the king’s court below.

“H… Her Majesty will tell you wh… what she wants done,” he said. “But I sh… should like one court planted with r… roses. Rose petals for throwing in masques.”

John nodded. A man who could turn from the death of his friend to the need of rose petals for masques would be a difficult master to love.

The king looked round, his eyebrow raised.

“Yes, Your Majesty,” John said from his place on the floor. He wondered what his master Sir Robert Cecil, who had scolded a greater monarch than this one, would have thought of a king who confided his grief in a gardener but left him kneeling on an arthritic leg.

There was a rustle of silk and high heels tapping.

“Ah! My gardener!” said the voice of the queen.

John, already low, tried to bow from a kneeling position and felt himself to be ridiculous. He glanced up. She was a short plump woman, beringed, curled, painted and patched with a low-cut gown which would have incurred Elizabeth’s censure, and a powerful scent of incense around her skirts which would have inspired outrage in the Ark at Lambeth. She gave him a bright dark-eyed smile and extended her small hand. John kissed it.

“Get up! Get up!” she commanded. “I want you to walk me all around the garden so that I can see what we must do!”

The flood of words came so quickly after her husband’s halting speech, and her accent was so strong, that John could not immediately understand what she said.

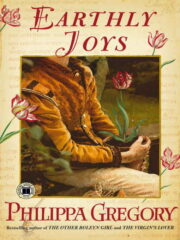

"Earthly Joys" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Earthly Joys". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Earthly Joys" друзьям в соцсетях.