“I’m stiff from sitting too long,” John said defensively.

“Oh, aye,” J said skeptically. “But how ever would you have managed a long sea voyage and then sleeping on the ground with winter coming? It would have been the death of you! It’s a blessing you didn’t go.”

John closed his eyes for a moment. “I know it,” he said shortly.

J led the way through the storeroom at the back of the shop and up the stairs to the living quarters. As they came into the parlor Elizabeth started forward and flung herself into her husband’s arms. “Praise God you are safe,” she cried, her voice choked with tears. “I never thought to see you again, John.”

He rested his cheek against the smoothness of her hair and the crisp laundered edge of her cap, and thought, but only for a moment, of a warm perfumed riot of dark curls and the erotic scratch of stubble. “Praise God,” he said.

“It was a blessing,” she said.

John met Josiah Hurte’s gaze over the top of his wife’s head. “No, it was an ill business,” he said firmly.

Josiah Hurte shrugged. “There are many that are calling it a divine deliverance. They are saying that Felton was the saviour of his country.”

“They are praising a murderer then.” Inside John’s head he could see Felton’s pale determined face at the moment when John could have called out, and did not. “It was a sin, and any that stood by and failed to prevent it are sinners too.”

Elizabeth, skilled with years of experience in reading John’s moods, pulled back a little so that she could see his grim expression. “But you could not have stopped it,” she suggested. “You were not the duke’s bodyguard.”

John did not want to lie to her. “I could have stopped it,” he said slowly. “I should have been closer to him, I should have warned him about Felton. He should have been better guarded.”

“No point in blaming yourself,” Josiah Hurte said briskly. “Better thank God instead that this country is spared a war and that you are spared the danger.”

Elizabeth said nothing; she looked into her husband’s face. “Anyway, you are free now,” she said quietly. “Free from your service to him, at last.”

“I am free at last,” John confirmed.

Mrs. Hurte gestured that he should take a place at the table. “We have dined because we did not know when to expect you, but if you will take a bowl of broth and a slice of pie, I can have it before you at once.”

John sat at the table and the Hurtes’ maid brought him small ale and food. Josiah Hurte sat opposite him and took a pint of ale to keep him company.

“No one knows what will happen to the duke’s estate,” Josiah said. “The family is still in hiding, and the London house is quite shut up. The servants have been turned away, and there’s no money to pay the tradesmen.”

“There never was any,” John remarked wryly.

“It may be that the family decide to sell up to cover their debts,” Josiah said. “If they decide to honor their debts at all.”

Mrs. Hurte was shocked. “They’ll never refuse to pay!” she exclaimed. “Good merchants will go bankrupt if they renege. His lordship had run bills for years; it would have been called treason to refuse him credit. What of the honest men who depend on his widow paying them?”

“They say that there is no money,” J said simply. “I have had no wages. Have you?”

John shook his head.

“What will we do?” Jane asked. She had one hand resting on the curve of her belly, as if she would protect the baby from even hearing of such troubles.

“You can stay here,” her father offered instantly. “If there’s nowhere else you can always stay here.”

“I promised to provide for her and I will,” J said, stung. “I can get a place at any house in the land.”

“But you swore you’d never work for a great lord again,” Jane reminded him. “Such work leads us into vanity and no man in the king’s service is to be trusted.”

John raised his head at such radical thoughts but Jane met his gaze without shrinking. “I am only saying what everyone knows,” she said steadily. “There are no good courtiers. There is none whom my John would happily call master.”

“I have a little land,” Tradescant said slowly. “Some woodland at Hatfield and some fields at New Hall. We could perhaps build a house near New Hall, near my fields, and set up on our own account…”

Elizabeth shook her head. “And do what, John? We have to find a business that will give us a living at once.”

There was a brief silence. “I know a man who has a house for sale on the south side of the river; it has an established garden and some fruit trees already planted,” Josiah said quietly. “There are fields around it that you could buy or rent as well. It was a little farm and now the farmer has died and his heirs are ready to sell. You might raise rare plants and trade as a plantsman and gardener.”

“How would we afford it?” John asked them. The purse containing the diamonds was heavy around his neck.

Elizabeth shot a quick collusive glance at her son, and then moved from the chair at the window and sat opposite her husband at the table. Her face was pale and determined. “There is a cart full of goods in the yard below,” she pointed out. “And another ship docked this morning with plants and curiosities for his lordship. If we sell the goods we can buy the house and the land. The rare plants and seeds you can nurse up and sell to gardeners. You’ve always said how difficult it is to get good stock for a garden. Remember how you traveled all around England for your trees? You could grow your stock and sell it.”

There was a tense silence in the little room. John absorbed the evidence that this was a plan, formed among the Hurtes and his family and now presented to him for his consent. He looked from Elizabeth’s determined face to J’s stoical blankness.

“You mean that we should take my lord’s goods,” John said flatly.

Elizabeth drew in a breath and nodded.

“That I steal from him?”

She nodded again.

“I cannot believe that this is your wish,” John said. “My lord has been dead and buried for a month and I am to steal from him like a dishonest pageboy?”

“There are the tulips,” J said in a sudden rush. His face was scarlet with embarrassment, but he faced his father as one man to another. “What would you have had me do? The tulips were ready for lifting, they were in their bowls in our garden, the place was in uproar, men were running out of the house with wall-hangings and linen trailing behind them. I did not know what to do with the tulips. Nobody there would have nursed them up. Nobody there knew what to do with them. Nobody would advise me.”

“So what did you do?” John asked.

“I brought them with me. And more than half of them have spawned. We have nigh on two thousand pounds’ worth of tulip bulbs.”

“Prices holding?” John’s acumen flared briefly, penetrating his grief.

“Yes,” J said simply. “Still rising. And we have the only Lack tulips in England.”

“How much are you owed?” Elizabeth suddenly demanded. “In back wages? Did he pay you for the last expedition to Rhé? Did he advance you wages for this one? Did he give you money for the cost of the journey to Portsmouth? Or for your stay in Portsmouth, or this journey home? Because if he gave you nothing you will never have more from the duchess. She is in hiding and the king himself is refusing to tell anyone where she is. They say she is afraid of assassins, but we all know she is more terrified of creditors. How much are you owed, John?”

“I was not paid at midsummer,” J reminded him. “They said they had no coin and gave me a note of promise, and I will not be paid this Michaelmas. That’s twenty-five pounds I am owed. And while you were away I had to buy some plants and some saplings and they could not repay me.”

Unconsciously John put his hand to his throat where the bag of diamonds nestled warm against his skin.

“You cannot agree to this?” He turned to Josiah. “It is theft.”

The merchant shook his head. “I no longer know what is right and wrong in this country,” he said. “The king takes money from the people without law or tradition, Parliament denies that he has the right, and so he closes Parliament and imposes the fines anyway. If the king himself can steal honest men’s money then what are we to do? Your lord stole your service from you for years, and now he is dead and no one will repay you. They will not even acknowledge the debt.”

“Stealing is still a sin,” John said doggedly.

“These are times when a man’s own conscience should be his guide,” Josiah replied. “If you think that he treated you fairly then deliver the goods to his house, pile riches upon riches and let the king take them to pay for his masques and vanities, as you know he will. If you think that the duke died owing you for your service, owing J, if you think these are times when a man does well to buy himself a little house and be his own master, then I think you would be justified in taking what you are owed and leaving his service. You should take only what you are owed. But you have a right to that. A good servant is worthy of his hire.”

“If you return the tulips to New Hall they will die of neglect,” J said quietly. “There is no one there to care for them, and then we will have killed the only Lack tulips in England.”

The thought of the waste of the tulips was as powerful as anything else for John. He shook his head like a bull does after a long baiting when it is so wearied that it longs for the dogs to close and make an end. “I am too tired to think,” he said. He rose to his feet but Elizabeth’s gaze held him.

“He hurt you,” she said. “On that last voyage to Rhé. He did something to you then that broke your heart.”

John made a gesture to stop her but she went on. “He sent you home with that pain in your heart, and then he recalled you, and he was going to take you to your death.”

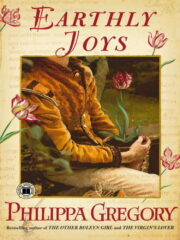

"Earthly Joys" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Earthly Joys". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Earthly Joys" друзьям в соцсетях.