The tulips that John had bought with such joy when he and his lord had been adventurers together in Europe, gambling with the crown jewels of England, flowered in their pots and Buckingham did not even see them. As soon as the precious blooms were over John set the pots outside in the dappled shade of his own garden so that he could water them daily and watch the leaves flop and droop, and pray that deep inside the soil the bulbs were growing plump and strong.

“When will we lift them?” J asked him, eyeing the dispiriting sight of the limp leaves.

“In autumn,” John said shortly. “And then we will know if we have made my lord a fortune, or if we have lost him one.”

“But either way he missed seeing the bloom,” J pointed out.

“He missed it,” John agreed. “And I missed showing it to him.”

Everyone in the town of Chelmsford, in the village of Chorley, in the kitchens at New Hall, and even the shepherds in the lambing pens spoke of nothing but the king and Parliament and the quarrel between them, the king and his wife and the quarrel between them, the quarrel between the king and the French, between the king and the Spanish, between the king and the Roman Catholics and between the king and the Puritans. Inside the enclosing walls of the duke’s park they did not dare say it, but in the ale houses of Chelmsford they had a joke which went: “Who rules the kingdom? The king! Who rules the king? The duke! Who rules the duke? The Devil!”

It would have been bad enough if it had stopped there, but the joke spread from the ale-house men to the women, who were more apt to see the work of the Devil in the gross injustice of life and took the jest too literally. From them it spread to the preachers, who knew that the Devil did his work daily, and that the richest pickings for him were around the king who could not rule his wife, nor his court, nor Parliament, nor protect his country.

They said that the duke was the most hated man in England. One of the garden lads, employed to scare crows off Tradescant’s new West Indian scarlet runner beans, boasted to another that they served a man worse-hated than the Pope. Everything was blamed on the duke: the plague which was again taking hundreds of men and women already weakened by a hungry winter, the wetness of the spring which would spoil the crops in the ground and, over and over again, the corruption of a king who surely would otherwise live in peace with his wife and strive to govern with Parliament.

The king was so desperate for money that he had called Parliament but the members, newly up from the country and determined to take a stand, had sworn that the king should have no money for any new wars without his signature on a Petition of Right. He must accept that there would be no taxes without their consent – no more illegal demands, no more royal charges – and that men who refused the whim of the king should not be sent to prison without a judge hearing their case. The king, bankrupt on his throne, was driven to assent, a grudging assent which he resisted to the last moment and regretted as soon as he had put his hand to the new contract.

Jane, on the settle at John’s fireside with her husband on a stool at her feet leaning his head against her knees, read the family her father’s letter.

“The king’s consent to the Petition of Right is seen as the start of a new era. It is hailed as a new Magna Carta which will defend the rights of innocent people against the wickedness of those who should be their betters and their guides. They are ringing the bells while I write this to celebrate the king’s agreement with Parliament at last. I wish I could say that His Majesty welcomes it as does everyone else, but he insists that it is nothing new, that there are no new freedoms, and therefore, that he is not curbed. The older men of my congregation remember that when Parliament came against Queen Elizabeth she thanked them kindly, and when she was forced to do as they wanted, she smiled as if it was her heart’s desire.

And the hot heads among my congregation are asking what will it take to teach this king to deal with his fellow men with respect?

At all events, he is to have the money he desires, and your husband’s master, the duke, is to take another campaign to Rhé…”

“What?” John said suddenly, interrupting Jane’s reading.

“He is to take another campaign to Rhé,” she repeated.

Elizabeth glanced at her husband. “You will never go! Not again, John. Not again, to there! Not even if he summons you.”

He jumped up from his chair and turned away from the circle of firelight and candlelight. She could see his hands, his whole body was trembling, but he spoke steadily. “If he summons me I will have to go.”

“It will be the death of you!” Elizabeth exclaimed passionately. “You cannot be so lucky every time!”

“It will be the death of thousands,” he said darkly. “Whether we take the island or lose it, it will be the death of thousands. I cannot face that place again. That tiny island is like a graveyard… I cannot bear it!”

Abruptly he turned back to Jane. “Does your father say why any man would want to go back there? What the duke is hoping for?”

She was pale, looking from John to Elizabeth. She thought she had never seen him in such distress before. It was as if he feared being press-ganged into Hell. “I will read you the rest of the letter,” she replied, smoothing it on her lap.

“…the duke is to take another campaign to Rhé to wipe out the disgrace of failure and to show the French that we mean to be masters. No men are volunteering, but the press-gangs are making the streets unsafe for everyone except for those actually dying of the plague. Everyone else is taken up and sent to Portsmouth and they are cursing the duke’s name.

These are hard times for us all. I pray that your husband and your father-in-law are spared the duke’s demands. I have today lost my apprentice boy George, whom I loved like a son. He will never survive a campaign; he has a weak chest and coughs all the winter long. Why take a lad of sixteen who will be dead before they reach their destination? Why take a boy who only knows about cotton, linen and silk?

I am going to Portsmouth myself to see if I can find him and bring him back but your mother says, rightly, that we must tell his parents that he is as good as dead and pray for his immortal soul.

It is a bitter thing that a country which could be at peace is constantly at war, and that a country which could be prosperous is never well-fed.

I am sorry to send you such bad news, my blessings on you all, Josiah Hurte.”

“I will go in your stead,” J said steadily. “When he sends for you.”

“He may not send…,” Elizabeth suggested.

“He always sends for my father when it is work that needs a trustworthy man,” J said swiftly. “When it is dangerous or difficult, when he needs a man who loves him above everything else. A man to do work that no one else would do.”

John shot him a look.

“It’s true,” J maintained. “And he will send for you again.”

“You cannot go,” Elizabeth breathed. “The mission is bound to fail again and you will risk your life for nothing.”

“My John can’t go,” Jane said suddenly. She made a small betraying movement, her hand to her belly. “I need him here.” She flushed. “We need him here. He is to be a father.”

“Oh, my dear!” Elizabeth stretched across the fire and held Jane’s hands in her own. “I am so glad! What a blessing.”

The two women remained clasped for a moment, and Elizabeth closed her eyes in a swift silent prayer. John watched them with a weary sense of exclusion from the world of small joys. “I am glad for you,” he said levelly. “And Jane is right, J cannot go with a baby on the way. If he sends for me, it will have to be me.”

The little family was silent for a moment. “Perhaps he will not send for you?” Jane asked.

John shook his head. “I think he will. And I have promised to go whenever he calls me.”

“To your death?” J demanded passionately.

John raised a weary face to his son. “Those were the very words of my oath,” he said slowly.

Summer 1628

The message came in the middle of June, one of the best months of the year for a gardener. John had started his day’s work in the rose garden, dead-heading the blowsy blooms and tossing the petals into a basket for the still room. They would be dried and used in pomanders, or for scattering in the linen cupboards to scent the duke’s sheets. Or they might be claimed by the cooks and candied to decorate the duke’s sweetmeats. Everything in the garden, from drowsily humming bees to falling rosy pale petals, was the duke’s and grew for his pleasure. Except he was not here to see them.

At midday John went around to the front of the house to see the young limes, planted in the long, gently curving double avenue. He had a thought that they might grow better-shaped if their lower branches were pruned, and he had a small axe and a saw for the purpose, and a lad coming behind with a ladder. But before he had done more than whistle to the lad to set the ladder before the first tree, he heard hoofbeats.

John turned, raised his hand to shield his eyes and saw, like a dream, like a long-awaited vision, the single rider still a mile off, his lathered horse going from gray to black as it passed from brilliant sunlight into deep green shadow down the drive. John stepped out from the shade of the trees on to the broad sunny road, waiting in the hot light for the messenger, knowing that it would be his summons, knowing that he must obey. He felt for a moment that it was Death himself, with his scythe over his shoulder, riding between the trees with the drunken bees buzzing wildly and the leaves dripping with nectar and pollen.

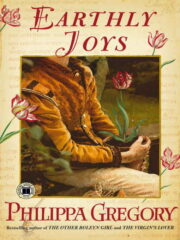

"Earthly Joys" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Earthly Joys". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Earthly Joys" друзьям в соцсетях.