He called to a sailor to bring him a boat.

The man reluctantly brought a little skiff to the foot of the ladder and John went down the side of the Triumph. The waves rose and fell under the keel of the little boat. John could see them, coming across the bay, frighteningly high from his low viewpoint in the water. The great swell of the Atlantic Ocean pushed them onward like an enemy to the little boats holding tightly to each other in a circle around the beleaguered fort.

“Take me round the point,” he said, raising his voice above the wind. “I want to see the barricade.”

The sailor leaned heavily on the oars and the skiff bobbed and fell as the big waves passed underneath. They rounded the point and John saw his barrier.

At first he thought it was holding. Squinting his eyes against the darkness he thought that the ships were still moored, nose to tail, and the unevenness of their rocking was the big waves passing through them, each one lifting and falling at a different moment. Then he saw that one had broken free.

“Damnation!” John yelled. “Get me on a ship! I have to raise the alarm.”

The sailor headed for one of the moored ships and John scrambled up the ladder. His bad knee failed him and he had to grab like a monkey with his arms and haul himself up the side. At the top he turned and shouted down. “Get you back to the Triumph. Tell the admiral that the barrier is breached. Tell him I’m doing what I can.”

The man nodded his agreement and set himself to row back to Buckingham’s ship while John flung himself on the bell and sounded the alarm. The sailors scrambled out of the waist of the ship, clutching their dinner – nothing more than a thin slice of rye bread and a thinner slice of French bacon.

“Get me a light,” John cried. “I need to signal to the ships to take that loose vessel up. The barrier is breached.”

“I thought they had surrendered!” the captain shouted as one of the men ran for a lantern.

“They sent terms,” John said. “His lordship is considering them.”

The captain turned and roared for a light and ordered the gunners to their posts. The signaling officer came running up with flaring torches. “Tell them to take up that ship,” John said.

The man ran forward and started signaling. John, looking past him, suddenly saw a gleam in the dark water, a reflection.

“What’s that?”

“Where?”

“In the water, beside that ship.”

One of the officers stared where John was pointing. “I can’t see anything,” he said.

“Hold a torch out!” John ordered.

They held a torch low over the water and saw the dark shadow of a French barge, rowed swiftly toward the gap in the barrier.

“To your places!” the captain yelled. John raced to the bell and rang it again. The gun crew opened the hatches and ran back the cannon for priming and loading; the soldiers poured out on deck. Someone lit and threw a flare toward the dark water below and in its briefly tumbling light John saw a string of barges rowing steadily and confidently from the papist camp around La Rochelle toward the fort of St. Martin.

From the other end of the barrier of English ships he heard the bells ringing for action stations. A single cannon started pounding in the darkness and then he felt the timbers under his feet shake at the explosion and recoil of the guns on his own ship. The loose ship which should have been lashed into the barrier was swinging wildly out of control, the crew swarming to get sails up, and to get her under way so that she could rejoin the line. But through the gap she had left the barges were pouring, heading straight for the citadel.

“A fire ship!” John gasped as he saw them launch the blazing raft toward the French barges from the English ships on the other side of the bay. One man stood at the back of the raft, courageously steering it straight toward the supply barges, the wind setting the flames in the bow leaping and crackling, reflected in the water until it looked as if the fires from hell were burning up from under the sea. The sailor stayed at his post until the last moment, until the heat beat him into the water, and the flames licked toward the kegs of powder. He dived off the back of the raft just as the charges on the fire ship exploded like celebration firecrackers. His head went deep under the water and for a moment John thought that the man was lost; then he came up, wet-headed like a seal, and swam to the nearest ship, clung to a rope and was hauled in.

The wind swung around; the unmanned fire ship, yawing wildly, blew before it, drifted away from the French barges and helpfully lit their way across the heaving glassy seas to the shore and the fort.

“Damnation!” Tradescant swore. “It’s going to miss them.”

Perilously the fire ship swung in a current and headed for the English line. The sailors scrambled to the side of the ship with buckets of water to try to douse the flames and poles to fend it off. By its brilliant flaring light the English gunners on the other ships could at last see their targets. The English guns pounded into life and John saw the French barges struck and men thrown into the water.

“Reload!” the gunners’ officer yelled from below. The deck of the ship heaved and thudded under John’s feet as the big guns fired and rolled back. Another direct hit, and another French vessel smashed amidships, men screaming as they were thrown into the rolling dark sea.

Squinting through the smoke, John could see that some of the barges were getting out of range, heading toward the citadel.

“Aim long!” he shouted. “Aim for the furthest barges!”

No one could hear him above the noise. Impotently, John saw the leading French barge run ashore below the castle on the tideline, the citadel’s sally port gates flung open in welcome, and a line of defenders rapidly form to unload the barges and throw sacks of food and supplies of weapons into the fort. John counted perhaps a dozen barges safely unloaded before the light from the fire ship died and the English gunners could no longer see their target, and the battle was lost.

The citadel was reinforced and revictualed and there would be no visit from Commander Torres to dine with the duke and accept his terms of surrender tomorrow.

John did not attend the council of war. He was in disgrace. His barrier had failed and the fort, so near to surrender, was eating better than the besieging English soldiers. While Buckingham took advice from his officers John walked away from the fort, away from the fleet, deep into the island, watching his feet for rare plants, his face knitted up in a scowl. The same pressures would still be working on the duke as before, but the situation was worse than ever. The fort was revictualed, the weather was deteriorating and on one of the ships there were two cases of jail fever. The cold weather would bring sickness and agues, and the men were underfed. They had the choice of sleeping in the open under pitiful shelters of bent twigs and stretched cloth and risking ague and rheums, or inside the ships packed like herrings in a barrel, risking fevers from the close quarters.

John knew that they must withdraw before the winter storms, and feared that they were mad enough to stay. He turned in his walk and went back toward the fort. One of the French sentries on the castle walls saw him and shouted a cheerful yell of abuse. John hesitated; then the message became clear. The sentry hauled up a pike with a huge joint of meat on the tip, to demonstrate their new wealth.

“Voulez-vous, Anglais?” he yelled cheerfully. “Avez vous faim?”

John turned and trudged back to the ill-named Triumph.

Buckingham was certain what they should do. “We must attack,” he said simply.

John gasped in horror and looked around the duke’s cabin. No one else seemed in the least perturbed. They were nodding as if this were the obvious course.

“But my lord…,” John started.

Buckingham looked across at him.

“They are better fed than us, they have almost limitless cannon and powder, they are mending the defenses and we know that the citadel is strong.”

Buckingham no longer laughed at John’s fears. “I know all that,” he said bitterly. “Tell me something that I have not thought of, John, or keep your peace.”

“Have you thought of going home?” John asked.

“Yes,” Buckingham said precisely. “And if I go now, with nothing to show for it, I can’t even be sure that I will have a home to go to.” He glanced around the cabin. “There are men still waiting to impeach me for treason,” he said bluntly. “If I have to die I’d rather do it here leading an attack than on the block outside the Tower.”

John fell silent. It was a measure of the duke’s desperation that he spoke so frankly before them all.

“And if I return home in disgrace and am executed then the prospects for all of you are not golden,” Buckingham pointed out. “I would not be in your shoes when you are asked what service you gave the king on the Ile de Rhé. I shall be dead, of course, so it will not trouble me. But you will all be hopelessly compromised.”

There was a little uncomfortable movement among the men in the cabin.

“So are we all decided?” Buckingham asked with a wolfish grin. “Is it to be an attack?”

“Torres cannot stand against us!” Soubise exclaimed. “He was ready to surrender once; we know the measure of the man now. He’s a coward. He won’t fight to the last; if we frighten him enough he will surrender again.”

Buckingham nodded to John as if there were no one else to convince. “That’s true enough,” he said. “We do know that he will surrender if he thinks a battle is lost. All we have to do is to convince him that the battle is lost.”

He leaned forward and spread out some papers on the table. John saw that they were his sketch plans, drawn when they were new to the island and his new gillyflower was heeled into his little nursery bed. Now it was rooted and putting out new shoots, and the sketches were dirty in the margin from much use.

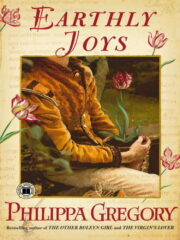

"Earthly Joys" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Earthly Joys". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Earthly Joys" друзьям в соцсетях.