“My lord!” Tradescant dropped the reins of his horse and went toward him. “I had thought you would sleep till noon!”

“I woke and thought of you setting off on your own adventure and I chose to come down to bid you farewell,” Buckingham said casually.

“I would have waited if I had known. I could have left later and you could have had your sleep.”

Buckingham slapped John on the shoulder. “I know. It doesn’t matter. I knew you were setting off early, and I woke and looked from my window and took a fancy to see you ride away.”

John said nothing; there were no words to say to the greatest man in England who rose at dawn after a night’s dancing to bid a servant farewell.

“Enjoy yourself,” Buckingham urged. “Stay as long as you like, draw on my banker, buy anything which takes your fancy and bring it home to New Hall. I want tulips next season, my John. I want thousands of beautiful tulips.”

“You shall have them,” Tradescant said fervently. “I shall give you gardens of great beauty, my lord. Great beauty.” He paused for a moment and cleared his throat. “And when am I to be home, my lord?”

Buckingham put his arm around John’s shoulders and hugged him tightly. “When you are ready, my John. Go and spend some money, and enjoy yourself. I have never been happier; you be happy too. Go and joyfully spend some of my easily earned money and we will meet again at New Hall when you come home.”

“I shall not fail you,” John promised, thinking that if he were not an honest man he could disappear into Europe with the heavy purses of gold and never be seen again.

“I know. You never fail me,” Buckingham said affectionately. “And that is why I want you to go and pleasure yourself with tulips. It is a reward for fidelity. If I cannot tempt you with easy French women and drink, then let me give you what is your greatest joy. Go and run riot in the bulbfields, my John. Lust after petals and slake your lust!”

He waved and turned inside the house. Tradescant waited, his hat in his hand, until the great double doors had closed behind his master, and then he mounted his horse, clicked encouragingly and turned its head eastward, out of Paris to the Low Countries and the tulip fields.

John found Amsterdam buzzing with infectious, continual excitement. All the taverns he had known where the tulip growers had met and sold tulips to one another were now expanded into double and treble the size and they opened for business in the morning in an atmosphere of teeth-gritting excitement. He looked in vain for the men he had known, the quiet steady gardeners who had told him how to cut the bulbs and plant them. They had been replaced by men with soft white hands who carried not bulbs but great books in which there were illustrations of tulips drawn with the beauty and care of fine portraits. The bidding for the bulbs was done on promisory notes; no money changed hands. John with his purses of French gold was an exception; he felt like a fool trying to pay men with money when everyone else was trading in credit.

And he felt even more of a fool when he tried to buy tulip bulbs to take away with him, when he wanted to exchange a sackful of gold – real money – for a sackful of bulbs – real bulbs. Everyone else was trading without ever holding a bulb in their hand. They bought and sold the promise of the tulip crop when it was lifted, or they bought and sold the name of a tulip. Some flowers were so rare that there were only ten or a dozen in the whole country. Such bulbs would never come to market, John was assured. He would have to buy the slip of paper with the name of the tulip written on the top of it, and have it attested at the Bourse. If he had any sense he would sell the slip of paper the very next day as the price jumped and leapfrogged. He should make his profit in the rising market and not hang around the dealers and ask them for real tulips to take home with him. The market was not for a bulb in a pot, it was for an idea of a tulip, the promise of a tulip. The market had gone light, the market had gone airy. It was the windhandel market.

“What’s that?” John asked.

“A wind market,” a man translated for him. “You are no longer buying the goods, you are buying the promise of the goods. And you are paying with a promise to pay. You don’t actually have to give your gold and receive your tulip until – oh – next year. But if you have any sense by then you will have sold it at a profit and you will have made a fortune merely by letting the wind blow through your fingers.”

“But I want tulips!” John exclaimed in frustration. “I don’t want a piece of paper with a tulip name written on it to sell to someone else. I want a bulb that I can take home and grow.”

The man shrugged, losing interest at once. “It’s not how we do business,” he said. “But if you go down the canal toward Rotterdam you will find men and women who will sell you bulbs that you can take away. They will call you a fool for paying money on the nail.”

“I’ve been called a fool before,” John said grimly. “I can bear it.”

He was dining in a tavern at the end of this expedition, drinking deep of the thick ale which the Dutch loved and eating well of their rich food, when the door darkened and a well-loved voice shouted into the gloom. “Is my John in here?”

John choked on his ale and leaped to his feet, overturning his stool. “Your Grace?”

It was Buckingham, modestly dressed in a suit of smooth brown wool, chuckling like a madman at the sight of John’s astounded face.

“Caught you,” he said easily. “Drinking away my fortune.”

“My lord! I never-”

He laughed again. “How have you done, my John? Are you rich in tulip notes?”

John shook his head. “I am rich in tulips, in real bulbs, my lord. The men in this town seem to have forgotten what they are buying and selling; they want only a piece of paper with a name written on it and the Bourse seal at the bottom. I had to go far inland to find growers who would sell me the real thing.”

Buckingham came into the ale house and sat at John’s table. “Finish your dinner; I have dined already,” he remarked. “So where are they? These tulips?”

“They are packed away and ready to sail tonight,” John said, reluctantly picking up a crust of bread smeared with creamy Dutch butter. “I was on my way home to New Hall with them.”

“Can they sail alone?”

John thought quickly. “I’d send a man I could trust to go with them. It’s too precious a cargo to leave to the captain. And I’d like someone to see them all the way to New Hall.”

“Do it,” the duke said idly.

John swallowed his question with his bread, rose from the table, bowed swiftly to the duke and went out of the tavern. He ran like a deer for his inn, engaged the landlord’s son to go to England and to see the barrels of tulips safely delivered to New Hall, pressed money and a note of introduction to J into the young man’s hand, and then ran back to the tavern as the duke was downing his second pint of ale.

“All done, Your Grace,” he reported breathlessly.

“I thank you,” the duke said.

There was a tantalizing silence. John stood before his master.

“Oh, you can sit down,” the duke said. “And have an ale. You must be thirsty.”

John slid into the seat opposite his master and watched him as the girl brought his drink. The duke was pale, a little tired from the festivities of the French court, but his dark eyes were sparkling. John felt a stir of his venturing spirit.

“Are you not attended, Your Grace?”

The duke shook his head. “I am traveling unknown.”

John waited but his master volunteered nothing.

“Anywhere to stay?”

“I thought I’d bed with you.”

“What if you had not found me?” John grimaced at the thought of the greatest man in England wandering around the Low Countries in search of his gardener.

“I knew I only had to wait somewhere near the tulip exchange and you would turn up,” Buckingham said easily. “And besides, I do not crumple without a dozen servants to support me, you know, John. I can fend for myself.”

“Of course,” John agreed quickly. “I just wondered what you are doing here?”

“Oh, that,” Buckingham said as if recalled to his mission. “Why, I have a job to do for my master and I thought you might help me.”

“Of course,” John said instantly.

“We’ll drink a little more and then roister a little, and then in the morning we shall do some business,” Buckingham suggested engagingly.

“Are we to go far?” John asked, thinking wildly of the ships which left for the Dutch Indies and for the spreading Dutch empire. “It may be that I should prepare while you make merry.”

The duke shook his head. “My business is in town, with the gold and diamond merchants. But I want you with me. My amulet. I shall need all my luck tomorrow.”

They slept in the same bed. When John woke in the morning the younger man had thrown an arm out in his sleep and John woke to a touch on his face like a caress. He lay still for a little while, under that casual blessing, and then slid out of bed and looked out of the little window down at the street below.

The cobbled quayside was crowded with sellers of bread and cheese and milk, up from the country by barge at dawn and spreading their stalls for all to see. Among them, and starting to lay out their wares, were the cobblers and sellers of household goods: brushes and soaps, kindling and brassware. Artists were setting up easels and offering to sketch portraits. Sailors up from the deep-water docks were moving among the crowd and offering rarities and foreign goods – silk shawls, flasks of rare drink, little toys. The low barges plied constantly up and down the canal; and ducks, in continual flurry away from the prows, quacked and complained. The sunlight glinted on the water of the canal and threw back the reflection of the market stalls and the dark shadows of the crisscrossing bridges.

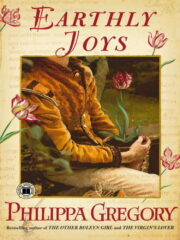

"Earthly Joys" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Earthly Joys". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Earthly Joys" друзьям в соцсетях.