“I’ll fetch her at once,” John said.

“Rest now, but go as soon as you wake,” the duke said and went quietly from the room.

John peeled the borrowed breeches off his sore buttocks, tumbled into the pallet bed and slept for six solid hours.

When he woke it was past noon. Someone had placed a jug and ewer on the dark wooden chest at the head of his bed, and he washed. In the chest was a change of clothes, and John slipped on a clean shirt and breeches. He did not trouble to shave. The duke’s mother could take him as he was. He went quietly down the stairs and out to the stable yard.

“I need a good horse,” he said to the chief groom. “The duke’s business.”

“He said you would be riding,” the man replied. “There’s a horse saddled and ready for you, and a lad to ride part of the way with you to bring back the horse when you need to change. In which direction are you going?”

“London,” John said briefly.

“Then this horse will take you all the way. He’s as strong as an ox.” The groom took in John’s stiff walk. “Though I imagine you’ll not be galloping.”

John grimaced and reached for the saddle to haul himself up.

“Where in London?” the groom asked.

“To the docks,” John lied instantly. “The duke has some curious playthings come from the Indies which he thought might amuse the king and divert him in his illness. I am to fetch them.”

“The king is better then?” the groom asked. “They said this morning he was on the mend, but I did not know. He has ordered his horses to move to Hampton Court so I thought he must be better.”

“Better, yes,” John said.

The groom released the reins and the horse took three steps back. With his bruised muscles aching, John leaned forward against the pain and sent his horse at the gentlest canter he could command, back down the road to London.

The countess was at her son’s grand London house. John went to the stables first and ordered them to harness the carriage for her, and then went into the house. She was a powerful old woman, dark-eyed like her son, but completely lacking his charm. She had been a famous beauty when she was a girl, married for her looks and jumped from servitude into the gentry in one lucky leap. But her struggle for respect had left its mark, her face was always determined; in repose she looked bitter. John recited his message in a whisper, and she nodded in silence.

“Wait for me downstairs,” she said shortly.

John went back down to the hall and sent a maidservant racing for some wine, bread and cheese. Within a few moments Lady Villiers was sweeping down the stairs, wrapped in a traveling cape, a pomander held to her nose against the infections of the London streets, a small box in her hand.

“You will ride in front to guide my driver.”

“If you wish, my lady.” John got stiffly to his feet.

She walked past him but as she got into the carriage she made a quick gesture with her hand. “Get up on the box; your horse can be tied behind.”

“I can ride,” John offered.

“You are half-crippled with saddle sores,” she observed. “Sit where you will be comfortable. You are of no use to my son or to me if you are bleeding from a dozen bruises.”

John climbed up to sit beside the driver. “Perceptive woman,” he remarked.

The driver nodded and waited for the carriage door to shut. John saw that he was holding the reins awkwardly with each thumb between the first and second finger: the old sign against witchcraft.

The roads were bad, thick with mud from the winter. In the heart of London, beggars held out beseeching hands as the rich carriage went by them. Some of them were pocked with rosy scars where they had recovered from the plague. The driver kept to the line of the track at a steady pace, and left it to them to leap clear.

“Hard times,” John remarked, thinking with gratitude to his lord of the little house at New Hall and his son and wife safely distant from these dangerous streets.

“Eight years of bad harvests and a king on the throne who has forgotten his duty,” the driver said angrily. “What would you expect?”

“I don’t expect to hear treason from the duke’s own household,” John said shortly. “And I won’t hear it!”

“I’ll say only this,” the driver said. “There’s a Christian prince and princess, his own daughter, driven from her throne by the armies of the Pope. There’s a Spanish match that he would still make if he could. The Spanish ambassador is to return to him – by his own request! And year after year the country gets poorer while the court gets richer. You can’t expect people to dance in the streets. The death cart goes past them too often.”

John shook his head and looked away.

“There’s those that think the land should be shared,” the driver said under his breath. “There’s those that think that no good will come to England while people starve every winter and others are sick of surfeit.”

“It is as God wills,” John insisted. “And I won’t say more. To speak against the king is treason; to speak against the way things are and must be is heresy. If your mistress heard you, you’d be on the street yourself. And me too, for listening to you.”

“You’re a good servant,” the man sneered. “For you even think in obedience to your lord.”

John shot him a hard dark look. “I am a good servant,” he repeated. “And proud of it. And of course I think in obedience to my lord. I think and live and pray in obedience to my lord. How else could it be? How else should it be?”

“There are other ways,” the driver argued. “You could think and live and pray for yourself.”

John shook his head. “I’ve given my allegiance,” he said. “I don’t withdraw it, and I don’t pay three farthings to the penny. My lord is my master, heart and soul. And you’ll forgive me saying, but you might be a happier man if you could say the same thing.”

The driver shook his head and sulkily fell silent. John wrapped himself in his borrowed cloak and nodded off to sleep, only waking when they were driving toward Theobalds under the great double avenue of ash and elm, with the daffodils flooding around the trunks.

The carriage drew up outside the door and the duke himself came out to greet his mother.

“Thank you, John,” he threw over his shoulder and drew her into the house and up to the king’s chamber.

“Is the king better?” John asked a manservant as the countess’s box was carried up the stairs.

“On the mend,” the man said. “He took some soup this midday.”

“Then I think I’ll take a turn around the garden.” John nodded toward the door and the enticing view. “If my lord wants me you will find me at the bath house, or on the mount. I have not been here for many years.”

He stepped through the front door and toward the first of the beautiful knot gardens. They wanted weeding, he thought, and then smiled at himself. These were not his weeds anymore, they were the king’s.

He saw Buckingham before dinner that night. “If you do not need me, I shall go home tomorrow,” he said. “I did not warn my wife that I was going with you, and there is much to do in the garden at New Hall.”

Buckingham nodded. “When you go through London you can see if my ship has come from the Indies,” he said. “And supervise the unloading of the goods. They were ordered to bring me much ivory and silk. You can fetch them safely down to New Hall and see them installed in my rooms. I am making a collection of rare and precious things. Prince Charles has his toy soldiers, have you seen them? They fire cannon and you can draw them up in battle lines. They are very diverting. I should like some pretty things too.”

“Am I to wait in London for the Indies goods to arrive?”

“If you will,” Buckingham said sweetly. “If Mrs. Tradescant can spare you so long.”

“She knows your service comes first,” John said. “How does the king today? Still better?”

Buckingham looked grave. “He is worse,” he said. “The ague has hold of him, and he is not a young man, and was never strong. He saw the prince privately today and put him in mind of his duties. He is preparing himself… I really think he is preparing himself. It is my duty to make sure he can be at peace, that he can rest.”

“I heard he was getting better,” John ventured cautiously.

“We give out the best reports we can, but the truth is that he is an old man who is ready to meet his death.”

John bowed and left the room, and went down to the hall for his dinner.

The place was in uproar. Half a dozen of the physicians that John had first seen in the king’s chamber were calling for their horses and their menservants. The courtiers were shouting for their carriages and for food to take on their journeys.

“What’s this?” John asked.

“It’s all the fault of your master,” a woman replied shortly. “He has flung the physicians from the king’s presence, and half the court too. He said they were troubling him too much with their noise and their playing, and he said the physicians were fools.”

John grinned and stepped back to watch the confusion of their departure.

“He will regret it!” one doctor shouted to another. “I warned him myself, if His Majesty suffers and we are not at hand, he will regret this insult to us!”

“He is beyond counsel! I warned him but he pushed me from the room!”

“He snatched my very pipe out of my mouth and broke it!” one of the courtiers interrupted. “I know that the king hates smoke, but it is a sure prevention of infection, and how should His Majesty smell it in another room? I shall write to the duke and complain of my treatment. Twenty years I have been at court, and he pushed me out of the door as if I were his serf!”

“He has cleared the room of everyone but a nurse, his mother and himself,” a man declared. “And he swears that the king shall have peace and quiet and no more meddling. As if a king should not be surrounded by his people all the time!”

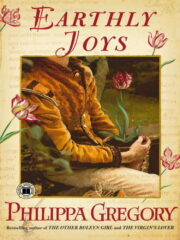

"Earthly Joys" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Earthly Joys". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Earthly Joys" друзьям в соцсетях.