It seemed odd, against the grain of all things, and wrong in itself that the heir she had never seen, whose name she had hated, should cross her threshold and exclaim with greedy pleasure at her carved and gilded wooden bed where he would now lie, the rich curtains around it and the hangings on the walls. “This is a palace fit for a king indeed,” James said, his chin wet as if he were salivating at the sight.

Sir Robert bowed. “I shall leave you to take your ease, Your Majesty.”

Already the room was losing that slight scent of orange blossom. The new king smelled of horses and of stale sweat. “I shall dine at once,” he said.

Sir Robert bowed low and withdrew.

John had the final ordering of the vegetables to the kitchen, checking the great baskets as they went from the cold house in the kitchen garden into the back door of the vegetable kitchens, and so he did not see the royal entourage arrive. The palace kitchens were in uproar. The meat cooks were sweating and as red as the great carcasses, and the pastry chefs were white with flour and nerves. The three huge kitchen fires were roaring and hot and the lads turning the spits were drunk with the small ale they were downing in great thirsty gulps. In the rooms where the meat was butchered for the spit the floor was wet with blood and the dogs of the two households were everywhere underfoot, lapping up blood and entrails.

The main kitchen was filled with servants running on one errand or another, and loud with shouted orders. John made sure that his barrows of winter greens and cabbage had gone to the right cook and made a hasty retreat.

“Oh, John!” one of the serving maids called after him and then blushed scarlet. “I mean, Mr. Tradescant!”

He turned at the sound of her voice.

“Will you be taking your dinner in the great hall?” she asked.

John hesitated. As Sir Robert’s gardener he was undoubtedly one of his entourage, and could eat at the far end of the hall, watching the king dine in state. As one of the household staff he could eat in the second sitting for the servers and cooks, after the main dinner had been served. As Sir Robert Cecil’s trusted envoy and the planner of his garden he could eat at a higher table, halfway up the hall: below the gentry of course, but well above the men at arms and the huntsmen. If Sir Robert wanted him nearby he might stand at his shoulder while his lord was served with his dinner.

“I’ll not eat today,” he declared, avoiding the choice which brought with it so many complexities. Men would watch where he sat and guess at his influence and intimacy with his master. John had long ago learned discretion from Sir Robert; he never flaunted his place. “But I’ll go into the gallery to watch the king at his vittles.”

“Shall I bring you a plate of the venison?” she asked. She stole a little glance at him from under her cap. She was a pretty girl, an orphan niece of one of the cooks. Tradescant recognized, with the weary familiarity of a man who has been confined to bachelorhood for too long, the stirring of a desire which must always be repressed.

“No,” he said regretfully. “I’ll come to the kitchen when the king is served.”

“We could share a plate, and some bread, and a flagon of ale?” she offered. “When I’ve finished my work?”

John shook his head. The ale would be strong, and the meat would be good. There were a dozen places where a man and a maid might meet in the great house alone. And the gardens were John’s own domain. Away from the formality of the knot gardens there were woodland walks and hidden places. There was the bathing house, all white marble and plashing water and luxury. There was a little mount with a summerhouse at the pinnacle, veiled with silk curtains. Every path led to an arbor planted with sweet-smelling flowers; around every corner there was a seat sheltered with trees and hidden from the paths. There were summer banqueting halls; there were the dozens of winter sheds where the tender plants were nursed. There was the orangery scented with citrus leaves, with a warm fire always burning. There were potting sheds, and tool stores. There were a thousand thousand places where John and the girl might go, if she were willing, and he were reckless.

The girl was only eighteen, in the prime of her beauty and her fertility. John was a cautious man. If he went with her and she took with child he would have to marry her, and he would lose forever his chance of a solid dowry and a hitch up the long small-runged ladder which his father had planned for him when he had betrothed him, two years ago, to the daughter of the vicar at Meopham in Kent. John had no intention of marrying before he had the money to support a wife, and no intention of breaking his solemn betrothal. Elizabeth Day would wait for him until her dowry and his savings would make their future secure. Not even John’s wage as a gardener would be enough for a newly married couple to prosper in a country where land prices were rising and the price of bread was wholly dependent on fair weather; and if the wife proved fertile then they would be dragged down to poverty with a new baby every year. John had an utter determination to keep his place in the world and, if possible, to improve it.

“Catherine,” he said. “You are too pretty for my peace of mind, I cannot go courting with you. And I dare not venture more…”

She hesitated. “We might venture together…”

He shook his head. “I have nothing but my wages, and you have no portion. We should do poorly, my little miss.”

Someone shouted for her from the kitchen table. She glanced behind her, chose to ignore them and stepped closer to him.

“You’re paid a vast sum!” she protested. “And Sir Robert trusts you. He gives you gold to buy his trees, and he is high in favor with the king. They say he is certain to take you to London to make his garden there…”

John hid his surprise. He had thought that she had been watching him and desiring him, as he, despite his caution, had been watching and wanting her. But this careful planning was not the voice of a besotted eighteen-year-old. “Who says this?” he asked, carefully keeping his voice neutral. “Your uncle?”

She nodded. “He says you are set fair to be a great man, although you are only a gardener. He says that gardens are the fashion and that Mr. Gerard and you are the very men. He says you could go as far as London. Perhaps even into the king’s service!” She broke off, excited by the prospect.

John had disappointment like a sour taste in his mouth. “I might.” He could not resist testing her liking for him. “Or I might prefer to stay in the country and try my hand at breeding flowers and trees. Would you come with me, to a little cottage, if I become a gardener in a small way, and husband a little plot?”

Involuntarily she stepped back. “Oh, no! I couldn’t bear anything mean! But surely, Mr. Tradescant, that is not your wish?”

John shook his head. “I cannot say.” He felt himself fumbling for a dignified retreat, conscious of the desire in his face, the heat in his blood and the contradictory, sobering awareness that she had seen him as an opportunity for her ambition, and never looked at him with desire at all. “I could not promise to take you to London. I could not promise to take you anywhere. I could not promise wealth or success.”

She pouted her lower lip, like a child who has been disappointed. Tradescant put both his hands in the deep pockets of his coat so that he would not be able to put them around her yielding waist, and pull her to him for consolation and kisses.

“Then you may fetch your own dinner!” she cried shrilly and turned abruptly away from him. “And I’ll find a handsome young man to dine with. A Scotsman with a place at court! There are many who would be glad to have me!”

“I don’t doubt it,” John said. “And I would too, but…” She did not wait to hear his excuses; she flounced around and was gone.

A serving man pushed past him with a huge platter of fine white bread; another ran behind with flagons of wine clutched four in each hand. John turned from the noise of the kitchen area and went toward the great hall.

The king was seated, drinking red wine at the enormous hearthside. He was already vastly, deeply drunk. He was still filthy from the day’s hunting and the travel along the muddy roads and he had not washed. Indeed, they said that he never washed, but merely wiped his sore and blotchy hands gently on silk. The dirt beneath his fingernails had certainly been there since his triumphant arrival in England, and probably since childhood. Sitting beside him was a handsome young man dressed as richly as any prince but who was neither Prince Henry the older son and heir nor Prince Charles the younger brother. As John waited at the back of the hall and watched, the king pulled the youth toward him and kissed him behind his ear, leaving a dribble of red wine along the pleats of his white ruff.

There was a roar of laughter at some joke and the king plunged his hand into the favorite’s lap and squeezed his padded codpiece. The man snatched up the hand and kissed it. There was high ribald laughter, from women as well as men, sharing the joke. No one paused for a moment at the sight of the King of England and Scotland with his dirty hand thrust into the lap of a man.

John watched them as if they were curiosities from another country. The women were painted white from their large horsehair wigs to their half-naked breasts, their eyebrows plucked and shaped so their eyes seemed unnaturally wide, their lips colored pink. Their gowns were cut low and square over their bulging breasts and their waists were nipped in tight by embroidered and jewel-encrusted stomachers. The colors of the silks and satins and velvet gowns glowed in the candlelight as if they were luminous.

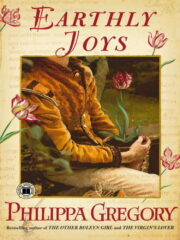

"Earthly Joys" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Earthly Joys". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Earthly Joys" друзьям в соцсетях.