J nodded, accepting the compromise. Elizabeth found that she had been gripping her hands tightly together under the cover of her apron, and released her grasp. “Tradescant and son,” John said, pleased.

“Tradescant and son,” J replied.

“Of Canterbury,” Elizabeth added, and saw her husband smile.

Spring 1620

“They say that Algiers is a town which cannot be taken,” Elizabeth said to John on the quayside, refusing to be optimistic even at this last moment.

“You are too doubting,” John said mildly. “Algiers can be defeated; no town is invincible. And the pirates who use it as their base must be stopped. They cruise in the English Channel, even up the Thames. The king himself says that they must be taught a lesson.”

“But why should it be you that goes?” she demanded.

“To go plant-hunting in the meantime,” John replied mildly. “Captain Pett said he was shorthanded for officers and he would take me. I told him that I would want the ship’s boat to call on shore wherever we could. It’s a bargain on both sides.”

“You won’t take part in any battles?” Elizabeth pressed him.

“I shall do my duty,” John said firmly. “I shall do whatever Captain Pett commands.”

Elizabeth curbed her anger and put her arms around her husband’s broadening middle. “You’re not a young man anymore,” she reminded him gently.

“For shame,” John said. “When my wife is a girl still.”

She smiled at that but he could not divert her. “I wanted you to stay home with us.”

He shook his head and gently kissed the warm top of her white cap. “I know, my love, but I have to go when there is a chance for me like this one. Be generous and send me away with a smile.”

She looked up at his face and he saw that she was closer to tears than to smiles. “I hate it when you go,” she repeated passionately.

John kissed her on the mouth, on the forehead as he had first done when they were betrothed, and then again on the lips. “Forgive me,” he said. “And give me your blessing. I have to go now.”

“God bless you,” she said reluctantly. “And bring you safe home to me.”

“Amen,” he replied, and before she could say more he had slipped out of her arms and run up the gangplank to the pinnace Mercury.

She did not wait to see his ship sail this time. She had good reason to hurry home. J would be back from school in the afternoon and she had planned to take a lift on the Canterbury wagon which went from Gravesend at midday. But in truth she did not wait because she was angry and resentful, and because she did not want to stand on the quayside like a lovelorn girl to wave her husband good-bye. She could not help but think that it was an infidelity to her and to his promise to stay home and dig his garden. She could not help but think the less of him that he could not resist the temptation of adventure.

John, looking down from the deck at the small indomitable figure walking stiff-backed away from the quayside, knew some of what was in her mind and could not help but admire her. He knew also that she would have been a happier wife coupled with another man, one who stayed at home and only heard travelers’ tales in the village inn. And that he too would have been a happier man married to a woman who could wave good-bye and greet him home with a broad smile and not cling to him on leaving, nor greet him resentfully on his return. But it was not a love match between John and Elizabeth and it never had been. What love they had found, and what love they had made, had been a benefit which neither they, nor their fathers who had wisely made the match, could have predicted. It was a marriage which was primarily designed to resolve some debts. It was a marriage designed to place Elizabeth’s dowry in the hands of a man who could make use of it, and place John’s skills at the disposal of a woman who would know how to manage a house that should grow in size and splendor with every move. The old men had chosen well. John was richer every year with his wages and with his burgeoning trade in rare plants. Elizabeth managed the Canterbury house as she had managed the new house at Hatfield, as she had managed the cottage at Meopham – with confidence and honesty. She had managed the vicarage and farmhouse for Gertrude; she could cope with bigger houses than her marriage had yet brought her.

But their fathers never provided for temperament and desire and jealousy. And the marriage they made never had room for such emotions either. As John watched Elizabeth walk away from the quay and as the Mercury slipped its moorings and the barges took it in tow, he knew that she would have to come to terms with the disappointments of the marriage as well as its benefits. He knew that she would have to recognize that her husband was a venturer, an adventurer. And that when he came home she would have to know that he was a man who could not resist the chance of traveling overseas. And that when the chance came for him – he would always go.

John’s Mediterranean voyage took him to Malaga, to join the rest of the English fleet in readiness for the assault on Algiers, and then they sailed in force to Majorca for revictualing. At both stops John begged for the use of the ship’s boat and went ashore with his satchel and his little trowel; he came back with his satchel bulging.

“You look as if you have murdered a dozen infidels,” Captain Pett said as Tradescant returned, mud-stained and smiling through the Mediterranean sunset.

“No deaths,” John said. “But some plants which will make my name.”

“What’ve you got?” the captain asked idly. He was not a gardener and only indulged John’s enthusiasm for the undeniable benefit of having a steady and experienced man on board who might command a troop of men if needed.

“Look at this,” John said, unpacking his muddy satchel on the holystoned deck. “A starry-headed trefoil, a sweet yellow rest harrow, and what d’you think this is?”

“No idea.”

“A double-blossomed pomegranate tree,” John said proudly, producing a foot-long sapling from his satchel. “I’ll need a barrel of earth for this at once.”

“Can it grow in England at all?” Captain Pett asked curiously.

Tradescant smiled at him. “Who knows?” he said, and the captain suddenly realized the joy that fired his temporary maverick officer. “Who can tell? We grow a cultivated sort in the orangeries. This is far more fragile and lovely. But I shall have to try it. And if I win, and we can grow wild pomegranates in England, then what a glory to God! For every man who walks in my garden can see things that until now he would have had to travel miles to find. And he can see that God has made things in such variety, in such glorious wealth, that there is no end to His joy in abundance. And no end to mine.”

“Are you doing this for the glory of God?” Captain Pett asked, slightly bemused.

John thought for a moment. “To be honest with you,” he said slowly, “I cling to the thought that it is for the glory of God. Because the other thought is heresy.”

Captain Pett did not glance around, as he would have done on land. He was master of his own pinnace and speech was free. “Heresy? What d’you mean?”

“I mean that either God has made dozens, even hundreds, of things which are nearly the same, and that the richness of his variety is something which redounds to His holy name…”

“Or?”

“Or that this is madness. It is madness to think that God should make a dozen things almost the same but a little different. All a man of sense could think is that God did not make them. That the earth they feed on and the water they drink makes plants in different areas a little different, and that is the only reason that they are different. And if that is true, then I am denying that everything in the world was made first by my God in Eden, working like a gardener for six days and resting on the Sabbath. And if I am denying that, then I am a heretic damned.”

Captain Pett paused for a moment, following the twisting path of Tradescant’s logic, and then let out a crack of laughter and hammered Tradescant on the shoulder. “You are trapped,” he exclaimed. “Because every variety that you discover must make you doubt that God could do all this in six days in Eden. And yet what you say you want to do is to show these things to the glory of God.”

Tradescant recoiled slightly from the loud good humor of his captain. “Yes.”

The captain laughed again. “I thank God I am a simple man,” he said. “All I have to do is to sack Algiers and teach the Barbary pirates that they cannot hazard the lives of English sailors. Whereas you, Tradescant, have to spend your life hoping for one thing but continually finding evidence to the contrary.”

A familiar stubborn look came across John’s face. “I keep faith,” he said stolidly. “Whether to my lord or to my king or to my God. I keep faith. And four sorts of smilax do not challenge my faith in God or king or lord.”

Pett was optimistic about the ease of his task, compared with John’s metaphysical worries. He was part of a well-victualed, well-commanded fleet with a clear plan. When they came to Algiers it was the task of the pinnaces to patrol the waterways to trap the pirates inside the harbor.

John and the other gentlemen recruited for the adventure were called into the captain’s cabin on the day the whole of the English fleet was assembled and moored in readiness half a league off shore.

“We’ll send in fireboats,” Pett said. “Two. They are to set the moored shipping ablaze and that will destroy the corsairs’ fleet. It’ll also spread smoke across the harbor and under cover of the smoke we’ll assault the walls of the harbor. That will be our task and that will be where you come in, gentlemen.”

He had a map unrolled before him on the table. The English fleet was shown as a double line of converging white flags with the distinctive red cross. The corsair ships were shown as a black square.

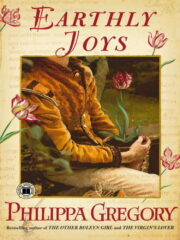

"Earthly Joys" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Earthly Joys". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Earthly Joys" друзьям в соцсетях.