“I shall stay some weeks with my wife,” he said to the gardener’s lad who held the horse. “You can send for me, if I am needed. Otherwise I shall come home at the end of September.” He did not notice he had called Theobalds “home.” “And have a care that you keep the gates shut,” he reminded the boy, “and weed the grass every day. But do not touch the roses; I shall be back in time to see to them myself. You may take the heads off when they are finished flowering, and take the petals to the still room, but that is all.”

It was a two-day journey to Meopham. John enjoyed traveling through the Surrey countryside where the hayfields were showing green again after the rain, and where the wheat stooks stood high in the field. Horsemen cantered past him, covering him in blinding clouds of dust; he sometimes rode alongside great wagons and could hitch his horse behind, taking a seat with the driver for a rest from the saddle and a sup of the driver’s ale. There were many people walking the roads: artisans on the tramp looking for work, harvesting gangs at the end of their season, apple-pickers making their way to Kent like John, gypsies, a traveling fair, a wandering preacher ready to set up at any crossroads and preach a gospel which needed neither church nor bishops, peddlers waddling beneath the weight of their packs, goose girls driving their flocks to the London markets, beggars, paupers and sturdy vagrants forced away from parish to parish, bullocks being driven to Smithfield by swearing, anxious cattle drovers.

In the inn at night John ate at an “ordinary,” the daily dinner with a set price which humble traveling men preferred, but he paid extra to sleep alone. He did not want to appear before Elizabeth scratching with another man’s fleas.

At the long dining table in the inn’s front room the talk was of the new king, who could not agree with Parliament although he had been in the kingdom only four years. The men dining at table were mostly on the side of the king. He had the charm of novelty and the glamour of royalty. So what if Parliament complained of the Scots nobles who hung around the court, and so what if the king was extravagant? The king of England could afford a little luxury, surely to God! And besides, the man had a family to support, a brace of princes and princesses; how else should he live but well? One man at the table had suffered at the hands of the Court of Wards and claimed that no man’s fortune was safe from a king who would take orphans into his keeping and farm out their fortunes among his friends, but he gained little sympathy. The complaint was an old one, and the king was new and novelty was a pleasure.

John kept his head down over his mutton and kept his own counsel. When someone shouted for a toast to His Majesty, John rose to his feet as swiftly as any man. He was not disposed to gossip about the painted women and painted boys of court, and besides, no man who had worked for Robert Cecil would ever voice a dangerous political opinion in a public place.

“I care nothing if we have no parliament!” a man exclaimed. “What have they ever done for me? If King James, God bless him, can do without a parliament – why! then so can I!”

John thought of his master, who believed that a monarch could only rule by a combination of bluff and seduction to gain the consent of the people, and whose watchword was practice not principle, kept silent, touched the chestnuts in his waistcoat pocket for luck, took up his hat and went from the room to his solitary bed.

He arrived at Meopham at noon and nearly turned into the courtyard of the Days’ family farmhouse, before he recalled that he should find Elizabeth in her new cottage – in their new cottage. He rode back down the mud track of the village street and then skirted around to the back of the little house where there was a lean-to shed and a patch of ground for his horse. He took off its saddle and bridle and turned the animal into the field. It raised its head and whinnied at the strangeness of the place and he saw Elizabeth’s face at an upstairs window, looking out at the noise.

As he walked toward the little cottage’s back gate he heard her running down the wooden stairs and then the back door burst open and she was racing toward him. As she suddenly recollected her dignity, she skidded to an abrupt halt. “Oh! Mr. Tradescant!” she said. “I should have killed a chicken if I had known you were coming today.”

John stepped forward and took her hands and kissed her, formal as ever, on her forehead. “I did not know what time I should arrive,” he said. “The roads were better than I thought they would be.”

“Have you come from Theobalds?”

“I left the day before yesterday.”

“And is everything well?”

“It is.” He glanced down at her and saw that her usually pale face was rosy and smiling. “You look very well… wife.”

She peeped up at him from under her severe white cap. “I am well,” she said. “And very happy to see you. The days are rather long here.”

“Why?” John asked. “I should have thought you would have much to do in a house of your own at last?”

“Because I am used to running a farmhouse,” she said. “With care for the still room, and the laundry, and the mending, and the feeding of the family and all the farm workers, and the health of the staff, the herb garden and the kitchen garden too! Here all I have to look after is two bedrooms and a kitchen and parlor. I have not enough to do.”

“Oh.” John was genuinely surprised. “I had not thought.”

“But I have started on a garden,” she said shyly. “I thought you might like it.”

She pointed to a level area of ground outside the back door. The ground was marked out with pegs and twines into a square shape containing the serpentine twists of a maze. “I was going to make it with chalk stones and flints in patterns of black and white,” she said. “I don’t think anything tender will thrive because of the chickens.”

“You can’t have chickens in a knot garden,” John said decidedly.

She chuckled and John looked down and saw with surprise that rosy happy face again. “Well, we have to have chickens for their eggs and for your dinner,” she said. “So you must think of a way that chickens can be kept out.”

John laughed. “At Theobalds I am plagued with deer!” he said. “It seems very hard that in my own garden I shall still have pests to come and spoil my plants.”

“Perhaps we could get another plot of land for the chickens,” she suggested. “And fence this off so that you might grow whatever you wish.”

John glanced down at the overworked light brown soil and the nearby midden. “It is hardly the ideal place,” he said.

At once he saw the color and the happiness drain from her face. She looked weary. “Not after Theobalds Palace, I suppose.”

“Elizabeth!” he exclaimed. “I did not mean…”

She turned away from him and was leading the way into the cottage.

He stepped after her and was about to take her hand but some stupid shyness checked the movement. “Elizabeth!” he said more gently.

She hesitated, but she did not turn. “I was afraid you were never coming back,” she whispered. “I was afraid that you had married me to fulfil the agreement, and to get my dowry, and that you would never come back to me at all.”

“Of course! Of course I would come back!” He was astounded at her. “I married you in good faith! Of course I would come back!”

She dipped her head down and then pulled up her apron to rub at her eyes. Still she did not turn around to him. “You did not write,” she said softly. “And it has been two months.”

Now it was he who turned away. He looked away from the house, over the little plot where his horse grazed, and toward the hill where the square-towered church pointed up at the sky. “I know,” he said shortly. “I meant to…”

She raised her head but still she did not turn around. He thought they must look a pair of fools, back to back in their own yard instead of in each other’s arms.

“Why did you not?” she asked softly.

He cleared his throat to hide his embarrassment. “I cannot write very fair,” he said awkwardly. “That is to say, I cannot write at all. I can read a bit, I can reckon very swiftly, but I cannot write. And anyway… I should not know what to say.”

She turned to him; but in his embarrassment, he did not see her. He was digging the heel of his riding boot into the corner of her little square of hen-scratched dust.

“What would you have said, if you had written?” she asked and her voice was very soft and tempting. It was a voice which a man would turn to and rest upon. John resisted the temptation to spin on his heel, snatch her up and bury his face in her neck.

“I would have said I was sorry,” he confessed gruffly. “Sorry to have been ill-tempered on our wedding night, and sorry that I had to leave you that very morning. When I was angry with them for making a noise I had thought that we would have the next day in peace, and that anything troublesome could be mended then. I had thought to wake early in the morning and love you then. But then the message came and I went up to London and there was no way of telling you that I was sorry.”

Hesitantly she stepped forward and put a hand on his shoulder.

“I am sorry too,” she said simply. “I thought these things were easier for men. I thought that you were doing just exactly what you wished. I thought that you had not bedded me because…” her voice became choked and she ended in a thin whisper “…because you have an aversion to me, and that you went back to Theobalds to avoid me.”

John spun around and snatched his wife to his heart. “I do not!” He felt her whole frame convulse with a deep sob. “I do not have an aversion!”

She was warm in his arms and her skin was soft. He kissed her face and her wet eyelids, and her smooth sweet neck and the dimples of her collarbone at the neck of her gown, and suddenly he felt desire sweep over him as easy and as natural as a spring rainstorm across a field of grass. He scooped her up and carried her into the house and kicked the door shut behind him, and he laid her down on the hearthrug before the little spinster’s fire where she had sat, alone and lonely, for so many evenings, and loved her until it grew dark outside and only the firelight illuminated their enfolded bodies.

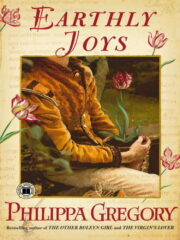

"Earthly Joys" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Earthly Joys". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Earthly Joys" друзьям в соцсетях.