Still, he is a little let down when Roy stops the bus and someone climbs aboard. But the noise and commotion are like steps descending into the day. He sits with his books in his lap, watching the back of Roy's head.

At the high school, Nathan hurries off the bus with the mass of kids, barely daring to nod goodbye. Roy concurrently makes a show of stacking his books.

For lunch, Nathan seeks out a new corner and keeps his back to the general congregation. He hardly dares wish that Roy would come, but, curiously, feels no surprise when he looks up and Roy is there. Roy ambles uncertainly with his tray before taking the facing seat. He glares at his plate like the first day. The wordless hinterland rises between them.

But he has come, whether they speak or not. The ritual of the cigarette also remains true to the past, the indolence of lounging on the patio beneath the swirls of smoke, Burke and Randy each handing Roy a free filter tip. They talk about swimming at the railroad trestle Friday afternoon, they relive the fantastic leaps of Burke and Roy. The memory of the day seems far away to Nathan. The wind over the cornfield, over the flat countryside, washing the patio, consumes him. The wind pours across the ground in rising waves. The flare of an acrid match in cupped palms sends smoke along Roy's cheeks. Cigarettes bravely burn.

After school, at the end of the ride home, Roy parks the orange bus in the yard, under the sycamore, and Nathan feels the heaviness of home.

They have been silent, the two boys, the whole afternoon ride. Safety can be found in spaces without words, where they are close together. Nathan is acute to some new change in Roy, some edge beyond his anger. The awareness has been building through the day and returns in force. Roy slides his books under his arms. He is delaying his departure. He affects to scan the floor with a critical eye. "I don’t think I need to sweep."

Nathan dares no answer.

"There's some paper. But I can pick that up."

The distilled thread of television reaches them from one or the other of the houses. At the moment Roy and Nathan each seem alien to those clusters of rooms. But still there is some mistrust in Roy, some hidden resistance. They glance about. Nathan begins a step past the older boy. He can already feel the ground beneath his feet.

"Maybe you ought to come to my house tonight," Roy says.

Nathan hesitates, a split second. Too long to pretend he did not hear. "I don't think I can."

Because Roy is watching, Nathan has no choice but to head into the kitchen. He can feel Roy's eyes on his back the whole walk across the yard.

Mom freezes at the sink. Nathan softly closes the door. He says hello. After a moment she answers.

There is stillness. There is the monotone buzz of the Frigidaire. There is Mom's narrow back, the neat bow of her apron. There is the smell, antiseptic, of a freshly cleaned house. There is the neat kitchen, which lays itself out neatly in perpendiculars, squares, rectangles, diamonds. There is her voice, hardly audible, saying his supper will be ready soon. There is, pervasive, her fear, and its orbital chill permeates Nathan. There is also, suddenly, a past surrounding them both, resonant with the memories Nathan normally resists, the white spaces of time in which his Dad falls on him like snow. While Mother, adjacent, allows.

Now they cannot face each other, the mother and son. The rupture between them blossoms. Nathan heads upstairs, changes his clothes for the night. He is trembling for no reason.

He sits down to early supper in the kitchen, long before Dad comes home. She sets a plate before him, leaves the room. Her soft weight settles into a chair in the living room, followed by the whisper of Bible pages sliding across one another.

After supper he carries his plate to the sink. The sound alerts her to the end of his meal, but she remains out of sight, in that room where Nathan rarely ventures. For a moment, he wishes she would come and offer him something. Vague but comforting. He wishes she would come but she remains there. He eases out the back door into the night.

The house recedes. One by one his connections are falling away.

Tonight he does not even think about staying indoors. He carries his quilts out the back door brazenly. He wanders along the pond and by sunset he arrives in the Kennicutt graveyard with his coat and blankets. He sits at the base of the obelisk, the place where Roy first brought him, in sight of the stone angel with its chubby thighs. Listening to the wind, he warms himself under the quilts.

Tonight seems a little warmer than before. He sits quietly, the quilts heavy around his shoulders. He is more tired than he realizes and dozes suddenly, a burst of unconsciousness almost like an enchantment; and when he wakens, footsteps are crashing through the leaves and a shadow crosses his face.

In a panic, thinking Dad has found him, he rises, clutching the quilts. But the hands that take his shoulders are Roy's. Roy emerges out of darkness, they are facing each other. Uncomprehending, Roy. Looking Nathan up and down, astonished and then afraid. "How long have you been sitting out here?"

The decision to answer requires a moment of focus. "Since after supper."

Tree frogs are singing. The tenor of the birds has changed a little, the cries seem harsher tonight. The occasional cricket resounds. A mild October has yet to finish summer off. The two boys stand together in the sound of night. Warmth spreads through Nathan, and he can feel Roy's body yielding toward him.

They sit close on the blanket, without speaking. Their quiet draws them closer.

"You were out here last night too, weren't you?"

The memory is distant. "I got on the bus after a while."

They each reflect on the landscape. Roy asks no more questions. For a long time he cannot bring himself to look at Nathan at all, but Nathan waits.

Dad has been home a long time now. Nathan spots the dark shape of his car at its usual mooring. The cloud of his presence hangs over the house. But the fact of Roy makes the fact of Dad less fearsome, suddenly; Nathan contemplates the change with grave curiosity. He leans against Roy, who allows him closer.

They sit quietly for a long time. Finally Roy moves his mouth close to Nathan's ear. "I got to go inside pretty soon. My parents will be wondering where I am."

"It's okay. I'll be fine."

"You can't stay out here."

"Yes, I can."

Hesitation. Roy considers one question, refuses it, something helpless in his expression. "You should come to my house."

Nathan shakes his head. "Your parents will send me home."

Silence. Roy is wondering whether to ask what's wrong, Nathan can tell. But he rejects the notion, he is afraid to know. They stick to the practical.

"You can sleep in the barn tonight, I'll show you a place."

The voices of everything, of crickets and frogs and birds, collide with the rasp of wind through dry leaves in the trees overhead. Nathan trusts, and therefore neglects to argue. Roy pulls him close, like a brother.

They touch each other gently, without intent. Only once, when Nathan brushes his lips against Roy's throat, is there something else. Roy takes a sudden breath and grips Nathan's head with his hand. A moment of possession. And Nathan sees, in a fleeting way, the irony that what pleases him with Roy terrifies him with his father. He glimpses this, he has no words for the thought. The moment of dread soon passes.

Roy takes him to the barn through the back and shows him the mattress in the corner behind bales of hay. They cover it with yellowed newspaper and Nathan curls up in the quilts. Roy lingers a little while, till Nathan's eyes adjust to the light in the drafty structure. Light from the yard pours through chinks in the outer wall. An owl is hooting somewhere overhead. Roy leans over Nathan on the mattress, hesitant. The moment begins intimately but ends awkwardly, Roy decides against any touch, stands and wipes the back of his jeans. "You'll be safe in here. Okay? I have to go."

"Thanks." Studying the play of shadow on Roy's face. "Are you still mad at me?"

The question surprises Roy. For a moment he seems overwhelmed, though the question is very simple. "No, I'm not mad."

"I had fun the other night."

"So did I."

Nathan busies himself spreading the quilts. When Roy heads to his house, the open door floods the barn with light. He waits in the rectangle a moment, his long shadow bisecting the stream of light. But whatever weighs on his mind, he asks nothing.

The door swings closed and Nathan is alone. The barn seems larger now that it is all dark again. The quiet and stillness are welcome. Nathan lies back along the mattress, newspaper rustling. He inhales the aroma of old straw, the dusky undertones of dried manure, a whiff of rotted apple, other odors he cannot identify. Around him, shadow shapes are forming in the dim light that spills through the cracks in the walls; the stored farm equipment, the tractor and covered plows, protective, like sleeping giants. He studies the unfamiliar space and tries to make himself comfortable on the mattress, grateful that he is inside for the night. Tired after two nights of fitful rest, he sleeps more soundly than he would have thought possible.

In the morning, he wakens to the sight of Roy, who sits on the edge of the mattress. Nathan did not even hear the door open. "Good morning. Did you sleep?"

Nathan rubs his eyes. "Yes."

"Your mom is awake. The light's on in your kitchen."

Nathan stretches, sits up. "What time is it?"

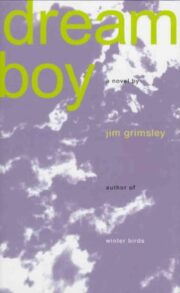

"Dream Boy" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Dream Boy". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Dream Boy" друзьям в соцсетях.