“If you mean, did Lord Vidal tell me so, no, sir, he did not. Lord Vidal is, I think, attached to his grace. I go by common report, a little, and by the very lively fear of her uncle evinced by my friend Miss Marling. His lordship merely gave me to understand that his father was uncannily omniscient, and had a habit of succeeding in all his objects.”

“I am relieved to hear that Lord Vidal has so much respect for his grace,” remarked the gentleman.

“Are you, sir? Well, having formed this opinion, I could not but feel that so far from desiring to meet me, his grace would very likely disinherit Lord Vidal if his lordship married me.”

“You draw an amiable portrait, Miss Challoner, but I can assure you that whatever his grace’s feelings might be he would never follow so distressingly crude a course.”

“Would he not, sir? I did not know, but I am very sure he would not countenance his son’s marriage to a nobody. To continue: Lord Vidal, discovering that I was once at school with his cousin, Miss Marling, brought me to Paris, and consigned me to her care until such time as he could find an English divine to marry me. Miss Marling was secretly betrothed to a certain Mr. Comyn, but their betrothal was broken off-irrevocably, as I thought-and Mr. Comyn, being a gentleman of great chivalry, offered his hand to me, to enable me to escape from Lord Vidal. Though I blush to confess it, sir, such was my desperate need, that I consented to elope with Mr. Comyn to Dijon where Lord Vidal had found an English divine. Unfortunately, Mr. Comyn thought it incumbent on him to leave a note for his lordship, apprising him of our intention to wed. The result was, sir, that Lord Vidal, accompanied by Miss Marling, overtook us at Dijon before the knot was tied. There was a painful scene. Mr. Comyn, desiring to protect me from his lordship’s-coercion-announced that we were man and wife. Lord Vidal, with the object of making me a widow, tried to choke the life out of Mr. Comyn. In which I think he would probably have succeeded,” she added, “had there not been a jug of water at hand. I threw it over them both, and my lord let Mr. Comyn go.”

“A jug of water!” he repeated. His shoulders shook slightly. “But continue, Miss Challoner!”

“After that,” she said matter-of-factly, “they fought with their swords.”

“How very enlivening! Where did they fight with-er-their swords?”

“In the private parlour. Juliana had hysterics.”

“It is quite unnecessary to tell me that,” he assured her. “What I should like to know is what was done with Mr. Comyn’s body?”

“He wasn’t killed, sir. No one was hurt at all.”

“You amaze me,” said the gentleman.

“Mr. Comyn would have been killed,” Miss Challoner admitted, “but I stopped it. I thought it was time.”

The gentleman surveyed her with distinct admiration, not untouched by amusement. “Of course I should have known that you stopped it,” he said. “What means did you employ this time?”

“Rather rough-and-ready ones, sir. I tried to catch the blades in a coat.”

“I am disappointed,” he said. “I had imagined a far neater scheme. Were you hurt?”

“A little, sir. His lordship’s sword scratched me, no more. That ended the duel. Mr. Comyn said that he must tell Lord Vidal the truth about us, and feeling myself somewhat shaken, I retired to my chamber.” She paused, and drew a long breath. “Before I had reached the stairway, his lordship’s mother arrived, accompanied, I think, by Lord Rupert Alastair. They did not see me, but I-I heard her grace-say to Lord Vidal-that he must not marry me, and I-I got into the diligence for Paris, which was at the door, and-and came here. That is all my story, sir.”

A silence fell. Conscious of her host’s scrutiny, Miss Challoner averted her face. After a moment she said: “Having heard me, sir, do you still feel inclined to assist me out of my difficulty?”

“I am doubly anxious to assist you, Miss Challoner. But since you have been so frank, I must request you to be yet franker. Am I right in assuming that you love Lord Vidal?”

“Too well to marry him, sir,” said Miss Challoner in a subdued voice.

“May I ask why ‘too well’?”

She raised her head. “How could I, sir, knowing that his parents would do anything in their power to prevent such a marriage? How could I let him stoop to my level? I am not of his world, though Sir Giles Challoner is my grandfather. Please do not let us speak any more of this! My mind is made up; my one dread now is that his lordship may pursue me to this place.”

“I can safely promise you, my dear, that while you remain under my protection you are in no danger from Lord Vidal.”

The words were hardly out of his mouth when the sound of voices outside came to Miss Challoner’s ears. She grew very white, and half rose from her chair. “Sir, he has come!” she said, trying to be calm.

“So I apprehend,” he said imperturbably.

Miss Challoner cast a frightened look round. “You promised I should be safe, sir. Will you hide me somewhere? We must be quick!”

“I still promise that you shall be safe,” he replied. “But I shall certainly not hide you. Let me recommend you to be seated once more… Come in!”

One of the inn servants came in looking rather scared, and firmly shut the door. “Milor’, there is a gentleman outside demands to see the English lady. I told him she was supping with an English milor’, and he spoke through his teeth, thus: ‘I will see this English milor’,’ he said. Milor’, he has the look of one about to do a murder. Shall I summon milor’s own servants?”

“Certainly not,” said milor’. “Admit this gentleman.”

Miss Challoner put out her hand impulsively. “Sir, I beg you will not! If my lord is in one of his rages I cannot answer for what he may do. I have a great alarm lest your years should not protect you from his violence. Is there no way I can escape from this room unseen?”

“Miss Challoner, I must once more request you to be seated,” said milor’, bored. “Lord Vidal will lay violent hands on neither of us.” He looked across at the serving-man. “I do not in the least understand why you are standing there goggling at me,” he said. “Admit his lordship.”

The servant withdrew; Miss Challoner, standing still beside her chair, looked down rather helplessly at her host. She wondered what would happen when my lord came in. A clock had chimed midnight somewhere in the distance not long since; it was a very odd hour at which to be found supping with a strange gentleman, however venerable he might be, and she feared that the Marquis’s jealous temper might flare up with disastrous results. There seemed to be no hope of making her host understand that the Marquis in a black rage was scarcely responsible for his actions. The gentleman was maddeningly imperturbable: he was even smiling a little.

She heard a quick step in the hall; Vidal’s voice said sharply: “Stable my horse, one of you. Where is this Englishman?”

Miss Challoner laid her hand on the back of her chair, and grasped it as though for support. The servant said: “I will announce m’sieur.”

He was cut short. “I’ll announce myself,” said his lordship savagely.

A moment later the door was flung open, and the Marquis strode in, his fingers hard clenched on his riding-whip. He cast one swift smouldering glance across the room, and stopped dead, a look of thunderstruck amazement on his face. “Sir!” he gasped.

The gentleman at the head of the table looked him over from his head to his heels. “You may come in, Vidal,” he said suavely.

The Marquis stayed where he was, one hand still on the doorknob. “You here!” he stammered. “I thought…”

“Your reflections are quite without interest, Vidal. No doubt you will shut that door in your own good time.”

To Miss Challoner’s utter astonishment the Marquis shut it at once, and said stiffly: “Your pardon, sir.” He tugged at his cravat. “Had I known that you were here-”

“Had you known that I was here,” said the elder man in a voice that froze Miss Challoner to the marrow, “you would possibly have made your entrance in a more seemly fashion. You will permit me to tell you that I find your manners execrable.”

The Marquis flushed, and set his teeth. An incredible and dreadful premonition seized Miss Challoner. She looked from the Marquis to her host, and her hand went instinctively to her cheek. “Oh, good God!” she said, aghast. “Are you-can you be-?” She could get no further.

The look of amusement crept back into the gentleman’s eyes. “As usual, you are quite right, Miss Challoner. I am that unscrupulous and sinister person so aptly described by you a while back.”

Miss Challoner’s tongue seemed to tie itself into knots. “I can’t-I would not-there is nothing I can say, sir, except that I ask your pardon.”

“There is not the smallest need, Miss Challoner, I assure you. Your reading of my character was most masterly. The only thing I find hard to forgive is your conviction that you had met me before. I don’t pretend to be flattered by the likeness you evidently perceived.”

“Thank you, sir,” said the Marquis politely.

Miss Challoner walked away to the fireplace. “I am ashamed,” she said. Real perturbation sounded in her voice. “I had no business to say what I did. I see now that I was quite at fault. For the rest-had I known who you were I would never have told you all that I did.”

“That would have been a pity,” said his grace. “I found your story extremely illuminating.”

She made a hopeless little gesture. “Please permit me to retire, sir.”

“You are no doubt fatigued after the many discomforts you have suffered to-day,” agreed his grace, “but I apprehend that my son-whose apologies I beg to offer-is come here expressly to see you. I really think that you would be well advised to listen to anything he may have to say.”

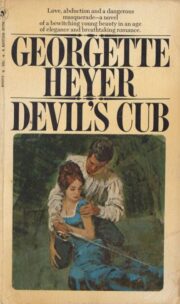

"Devil’s Cub" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Devil’s Cub". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Devil’s Cub" друзьям в соцсетях.