“The loss of your baggage is, I fear, beyond my power to remedy, but a bed-chamber I can procure for you at once.”

“I should be very grateful to you, sir, if you would.”

The Englishman turned to the landlord, who was humbly awaiting his pleasure. “Your stupidity, my good Boisson, is lamentable,” he remarked. “You will escort this lady to a suitable chamber.”

“Yes, monseigneur, yes indeed. It shall be as monseigneur wishes. But-”

“I do not think,” said the Englishman sweetly, “that I evinced any desire to converse with you.”

“No, monseigneur,” said the landlord. “If-if mademoiselle would follow my wife upstairs? The large front room, Celestine!”

Madame said resentfully: “What, the large room?”

The landlord gave her a push towards the stairs. “Certainly the large one. Go quickly!”

The Englishman turned to Miss Challoner. “You bespoke supper, I believe. I shall be honoured by your presence at my own table. Boisson will show you the way to my private salle.”

Miss Challoner hesitated. “A bowl of soup in my chamber, sir-”

“You will find it more entertaining to sup with me,” he said. “Let me allay your qualms by informing you that I have the pleasure of your grandfather’s acquaintance.”

Miss Challoner grew rather pale. “My grandfather?” she said quickly.

“Certainly. You said, I think, that your name is Challoner. I have known Sir Giles any time these forty years. Permit me to tell you that you have a great look of him.”

In face of this piece of information Miss Challoner abandoned her first impulse to disclaim all relationship with Sir Giles. She stood feeling remarkably foolish, and looking rather worried.

The gentleman smiled faintly. “Very wise,” he commented, with uncanny perspicacity. “I should never believe that you were not his granddaughter. May I suggest that you follow this worthy female upstairs? You will join me at your convenience.”

Miss Challoner had to laugh. “Very well, sir,” she said, and curtsied, and went off in the wake of the landlady.

She was allotted what she guessed to be one of the best chambers, and a serving-maid brought her water in a brass can. She emptied her reticule on to the dressing-table, and somewhat ruefully inspected the collection thus displayed. Luckily she had slipped a clean tucker into it, and when carefully arranged round her shoulders this concealed the tear in her gown. She combed out her hair, and dressed it again, washed her face and hands, and went downstairs to the hall.

The presence of a countryman had been providential, but that he should be acquainted with her grandfather, and knew her identity, was a calamity. Miss Challoner had no idea what she was going to say to him, but some explanation was clearly called for.

The landlord was awaiting her at the foot of the staircase, and he met her with a respect as marked as his late contempt. He led the way to one of the doors leading from the hall, and ushered her into a large parlour.

Covers were laid on the table in the centre of the room, and the apartment was lit by clusters of wax candles in solid chandeliers. Miss Challoner’s new friend was standing by the fireplace. He came forward to meet her, and taking her hand at once remarked on its coldness. She confessed that she was still feeling chilly, and told him that the stage had been full of draughts. She went to the fire, and spread out her hands to the blaze. “I find this very welcome, sir,” she said, smiling up at him. “You are indeed kind to invite me to sup with you.”

He surveyed her somewhat enigmatically. “You shall let me know later how I may serve you further,” he said. “Will you not be seated?”

She walked to the table, and sat down at his right hand. A liveried servant came in noiselessly, and set soup before them. He would have stayed behind his master’s chair, but a slight sign dismissed him.

Miss Challoner drank her soup, realising suddenly that it was many hours since she had partaken of food. She was relieved to find that her host did not seem to require an immediate explanation of her peculiar circumstances, but talked gently instead on a number of impersonal subjects. He had a caustic way with him, which Miss Challoner found entertaining. There was often a twinkle in her eye, and since her knowledge was sufficiently wide (for, unlike her friend Juliana, she had not wasted her time at school), she was able not only to listen, but to contribute her own share to the conversation. By the time the sweetmeats were set on the table she and her host were getting on famously, and she had quite lost any shyness that she might at first have felt. He encouraged her to talk, sitting back in his chair, sipping his wine, and watching her. To begin with, she had found his scrutiny a little trying, for his face told her nothing of what he might be thinking, but she was not the woman to be easily unnerved, and she looked back at him, whenever occasion demanded, with her usual friendly calm.

She could not be rid of the conviction that she had met him before, and the effort to remember where brought a crease between her brows. Observing it, her host said: “Something troubles you, Miss Challoner?”

She smiled. “No, sir, hardly that. Perhaps it is ridiculous of me to suppose it, but I have an odd feeling that I have met you before. I have not?”

He set his glass down, and stretched out his hand for the decanter. “No, Miss Challoner, you have not.”

She was tempted to ask his name, but since he was so very much older than herself she did not care to appear in the least familiar. If he wished her to know it no doubt he would tell her.

She laid down her napkin, and rose. “I have been talking a great deal, I fear,” she said. “May I thank you, sir, for a pleasant evening, and for your exceeding kindness, and so bid you good-night?”

“Don’t go,” he said. “Your reputation is quite safe, and the night is still young. Without wishing to seem idly curious, I should like to hear why you are journeying unprotected, through France. Do you think I am entitled to an explanation?”

She remained standing beside her chair. “Yes, sir, I do think it,” she answered quietly. “For my situation must seem indeed strange. But unhappily I am not able to give you the true explanation, and since I do not wish to repay your kindness with lies it is better that I should offer none. May I wish you good-night, sir?”

“Not yet,” he said. “Sit down, my child.”

She looked at him for a moment, and after some slight hesitation, obeyed, lightly clasping her hands in the lap of her grey gown.

The stranger regarded her over the brim of his wineglass. “May I ask why you find yourself unable to proffer the true explanation?”

She seemed to ponder her reply for a while. “There are several reasons, sir. The truth is so very nearly as strange as Mr. Walpole’s famous romance that perhaps I fear to be disbelieved.”

He tilted his glass, observing the reflection of the candlelight in the deep red wine. “But did you not say, Miss Challoner, that you would not lie to me?” he inquired softly.

Her eyes narrowed. “You are very acute, sir.”

“I have that reputation,” he agreed.

His words touched a chord of memory in her brain, but she was unable to catch the fleeting remembrance. She said: “You are quite right, sir: that is not my reason. The truth is there is someone else involved in my story.”

“I had supposed that there might be,” he replied. “Am I to understand that your lips are sealed out of consideration for this other person?”

“Not entirely, sir, but in part, yes.”

“Your sentiments are most elevating, Miss Challoner. But this punctiliousness is quite needless, believe me. Lord Vidal’s exploits have never been attended by any secrecy.”

She jumped, and her eyes flew to his face in a look of startled interrogation. He smiled. “I had the felicity of meeting your esteemed grandparent at Newmarket not many days since,” he said. “Upon hearing that I was bound for France he requested me to inquire for you on my way through Paris.”

“He knew?” she said blankly.

“Without doubt he knew.”

She covered her face with her hands. “My mother must have told him,” she said almost inaudibly. “It is worse, then, than I thought.”

He put his wineglass down, and pushed his chair a little way back from the table. “I beg you will not distress yourself, Miss Challoner. The role of confidant is certainly new to me, but I trust I know the rules.”

She got up and went over to the fire, trying to collect her thoughts, and to compose her natural agitation. The gentleman at the table took snuff, and waited for her to return. She did so in a minute or two, with a certain brisk determination that characterised her. She was rather pale, but completely mistress of herself. “If you know that I-left England with Lord Vidal, sir, I am more than ever grateful for your hospitality to-night, and an explanation is beyond doubt due to you,” she said. “I do not know how much you have learned of me, but since no one in England knows the whole truth, I fear you may have been quite misinformed on several points.”

“It is more than likely,” agreed her host. “May I suggest that you tell me the whole story? I have every intention of helping you out of your somewhat difficult situation, but I desire to know exactly why you left England with Lord Vidal, and why I find you to-day, apparently alone and friendless.”

She leaned towards him, her face eager. “Will you help me, sir? Will you help me to obtain a post as governess in some French family, so that I need not go back to England, but can maintain myself abroad?”

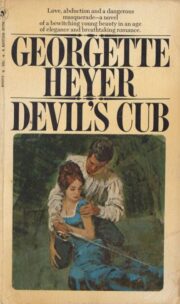

"Devil’s Cub" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Devil’s Cub". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Devil’s Cub" друзьям в соцсетях.