“You suggest, in fact, ma’am, that I should abduct Miss Marling? I fear I am quite unlearned in such ways. Her cousin, the Marquis of Vidal, would no doubt oblige her.”

Miss Challoner coloured, and looked away. Mr. Comyn, realising what he had said, coloured too, and begged her pardon. “I did not desire to elope with her, even were she willing,” he continued hurriedly. “But she deemed it our best course, and when I was urged to it by a member of her family, I allowed my scruples to be overruled, and came to Paris with the express intention of arranging a secret marriage.”

“Well, arrange it, sir,” Miss Challoner advised him.

“I had almost done so, ma’am. I may say that I bear in my pocket at this moment the direction of an English divine at present travelling through France on his way to Italy. I came here to-night expecting to see Juliana, and to tell her that we have nothing more to wait for. And I find that she has gone, in defiance of my expressed wish, to a ball where the chief-the sole attraction is the Vicomte de Valmé. Madam, I can only designate such conduct as heartless in the extreme.”

Miss Challoner paid very little heed to the last part of this speech, but said rather breathlessly: “You know of an English divine? Oh pray, sir, have you told my Lord Vidal?”

“No, ma’am, for-”

“Then do not!” Mary said, laying her hand on his. “Will you promise me that you will not tell him?”

“Madam, I regret infinitely, but you are under a misapprehension. It was Lord Vidal who told me.”

Mary’s hand fell again to her side. “When did he tell you?”

“This afternoon, ma’am. He was good enough, at the same time, to present me with a card for this ball at the Hôtel Saint-Vire. Apparently he knows his cousin better than I do. I never dreamed that she would go.”

“This afternoon… Oh, I hoped he would not be able to find a Protestant to marry us!” Mary exclaimed unguardedly. “What shall I do? What in the world shall I do?”

Mr. Comyn regarded her curiously. “Do I understand, ma’am, that a marriage with Lord Vidal is not your desire?”

She shook her head. “It is not, sir. I am aware that you must think my conduct-my compromising situation-”

She got up, averting her face.

Mr. Comyn also got up. He possessed himself of both her hands, and held them in a comforting clasp. “Believe me, Miss Challoner, I understand your feelings exactly. I have nothing but the deepest sympathy for you, and if I can serve you in any way I shall count it an honour.”

Miss Challoner’s fingers returned the pressure of his. She tried to smile. “You are very kind, sir. I-I thank you.”

The click of the door made her snatch her hands away. She turned, startled, and met the smouldering gaze of my Lord Vidal.

His lordship was standing on the threshold, and it was plain that he had seen Mary break loose from Mr. Comyn’s hold. His hand was resting suggestively on the hilt of his light dress-sword, and his eyes held a distinct menace. He was in full ball dress, all purple and gold lacing, with a quantity of fine lace at his wrists and throat.

To her chagrin Miss Challoner felt a blush steal up into her cheeks. She said with less than her usual composure: “I thought you had gone to the Hôtel Saint-Vire, sir.”

“So I infer, ma’am,” said his lordship with something of a snap. “I trust I don’t intrude?”

He was looking at Mr. Comyn in a way that invited challenge. Mary pulled herself together and said quietly: “Not in the least, sir. Mr. Comyn is on the point of departure.” She held out her hand to this young man as she spoke, and added: “You should use your card for the ball, sir. Pray do!”

He bowed, and kissed her fingers. “Thank you, ma’am. But I should be very glad to remain if you feel yourself to be at all in need of company.”

The meaning of this was quite plain. My lord strolled suggestively into the middle of the room, but before he could speak Miss Challoner said quickly: “You are very kind, sir, but I am shortly going to retire. Let me wish you good night-and good fortune.”

Mr. Comyn bowed again, favoured his lordship with a slight inclination of the head, and went out.

The Marquis watched him frowningly till he was out of the room. Then he turned to Miss Challoner. “You’re on terms of intimacy with Comyn, are you?”

“No,” replied Mary. “Hardly that, my lord.”

He came up to her, and gripped her by the shoulders. “If you don’t want to see a hole shot through that damned soft-spoken fellow you’d best keep your hands out of his. Do you understand, my girl?”

“Perfectly,” said Miss Challoner. “You’ll allow me to say that I find you absurd, my lord. Only jealousy could inspire you with this ill-placed wrath, and where there is no love there cannot be jealousy.”

He let her go. “I know how to guard my own.”

“I am not yours, sir.”

“You will very soon be. Sit down. Why are you not at the ball?”

“I had no inclination for it, sir. I might ask, why are not you?”

“Not finding you there, I came here,” he replied.

“I am indeed flattered,” said Miss Challoner.

He laughed. “It’s all I went for, my dear, I assure you. Why was that fellow holding your hands?”

“For comfort,” said Miss Challoner desolately.

He held out his own. “Give them to me.”

Miss Challoner shook her head. There was a curious lump in her throat that made speech impossible.

“Oh, very well, ma’am, if you prefer the attentions of Frederick Comyn!” said the Marquis in a hard voice. “Be good enough to listen to what I have to say. I have discovered, through Carruthers, of the Ambassador’s suite, that there is a divine, lately passed through Paris, bear-leading some sprig of the nobility. They are bound for Italy by easy stages, and at this present are to be found in Dijon, where it appears they are making a stay of two weeks. He’s the man to do our business for us. I am about to abduct you for the second and last time, Miss Challoner.” She made no reply. His eyes reached her face. “Well, have you nothing to say?”

“I have said it all so many times, my lord.”

He turned away impatiently. “Make the best of me, ma’am; you dislike me cordially, no doubt. I’ll admit you have reason. But you may know, if it interests you, that I am offering what I have never offered to any woman before.”

“You offer it because you feel you must,” said Mary in a low voice. “And I thank you-but I refuse your offer.”

“Nevertheless, ma’am, you’ll start with me for Dijon tomorrow.”

She raised her eyes to his face. “You cannot wrest me by force from this house, my lord.”

“Can’t I?” he said. His lip curled. “We shall see. Don’t try to escape me. I should run you to earth within a day, and if you put me to that trouble you might find my temper unpleasant.” He walked to the door. “I have the honour to bid you good night,” he said curtly, and went out.

Chapter XIII

meanwhile, to anyone who knew her, Miss Marling’s reckless air of gaiety that night would have betokened an inward disquiet. She seemed to be in the highest spirits, but her eyes were restless, always searching the fashionable throng.

Paris had gone to Miss Marling’s head, and the attentions of such a known connoisseur as the Vicomte de Valmé could not but flatter her. The Vicomte protested that his heart was under her feet. She did not entirely believe this, but a diet of admiration and compliments spoiled her for the criticisms of Mr. Comyn. When he first appeared at her cousin’s house she had tumbled headlong into his arms, but this first unaffected rapture suffered a check. She proceeded to pour into her Frederick’s ears a recital of all her pleasures and triumphs. He listened in silence, and at the end said gravely that although he could not but be glad that she had found amusement, he had not thought that she would be so extremely gay and happy away from him.

Partly because it was the fashion to be coquettish, partly from a feeling of guilt, Juliana had answered in an arch, provocative way that did not captivate Mr. Comyn in the least. Bertrand de Saint-Vire would have known just what to say. Mr. Comyn, unskilled in the art of flirtation, said that Paris had not improved his Juliana.

They quarrelled, but made it up at once. But it was an ill beginning.

Miss Marling made Mr. Comyn known to her new friends, amongst them the Vicomte de Valmé. Mr. Comyn, with a lamentable lack of tact, spoke disparagingly of the Vicomte, whom he found insupportable. Truth to tell, the Vicomte, who was well aware of Mr. Comyn’s pretensions, was impelled by an innate love of mischief to flirt outrageously with Juliana under the very nose of her stiff and disapproving lover. Juliana, anxious to awake a spark of jealousy in what at that moment seemed to her an unresponsive heart, encouraged him. All she wanted was to be treated to a display of ruthless and possessive manhood. If Mr. Comyn, later, had seized her in his arms in a decently romantic fashion there would have been an end to the Vicomte’s flirtation. But Mr. Comyn was deeply hurt, and he did not recognise in these signs a perverted expression of his Juliana’s love for him. He was young, and he handled the affair very ill. He was forbearing where he should have been violent, and found fault when he should have made love. Miss Marling determined to teach him a lesson.

It was this laudable resolve that took her to the Hôtel Saint-Vire. Mr. Comyn should learn that it was unwise to lecture and criticise Miss Marling. But because under her airs and graces she was really very much in love with him, she induced her cousin to provide him with a card for the ball.

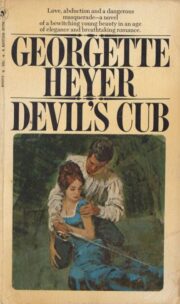

"Devil’s Cub" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Devil’s Cub". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Devil’s Cub" друзьям в соцсетях.