“It must undoubtedly go by canal,” said his grace, betraying a faint interest. He removed his ruffle from his wife’s clutch. “May I ask, Léonie, why you must needs elope with Rupert in this distressing fashion?”

“But do you not know, then?” she demanded. “If you don’t know, why are you here, Monseigneur? You are teasing me! Where is Dominique? Gaston said that he was with you.”

“He is,” said his grace.

“Then of course you know. Oh, Monseigneur, he says he will marry that girl, and I have a great fear she is like the sister whom I found detestable!”

The Duke took her hand and led her to Miss Challoner. “You shall judge for yourself,” he said. “This is Miss Challoner.”

The Duchess looked sharply up at him, and then at Mary, who stood still and looked gravely back at her. Léonie drew a long breath. “Voyons, are you the sister of that other one?” she demanded, not very lucidly.

“Yes, ma’am,” said Mary.

“Vraiment? But it is not at all credible, I find. I do not want to be rude, but — ”

“In that case, my love, you had better refrain from making the comparisons that are on the lips of your very unguarded tongue,” interposed his grace.

“I was not going to say anything indiscreet,” the Duchess assured him. “But I say one thing. If you do not like it, Monseigneur, I am sorry, but I am not going to permit that my son abducts this Mary Challoner and then does not marry her. I say he shall marry her at once, and Rupert shall fetch that Hammond person, who has the manners of a pig.”

“These continued references to Mr. Hammond — a gentleman quite unknown to me — I find most tedious,” complained his grace. “If his manners are those of a pig, I beg that Rupert will refrain from fetching him.”

“But you do not understand, Justin. He is a priest.”

“So I have been led to infer. I believe it will not be necessary for us to disturb him.”

The Duchess took Miss Challoner’s hand, and held it. She faced her husband resolutely. “Monseigneur, you must listen to me. When I thought that this child was — was — ”

“Pray do not continue, my dear. I understand perfectly. If you will permit me to — ”

“No, Monseigneur,” she said firmly. “This time it is I who must speak. When I thought this child was not a respectable person, I said Dominique should not marry her. I made Rupert bring me to Dijon because I thought I would be very clever and arrange everything so that you would never know — ”

“This touching but misplaced confidence in your powers of concealment, ma mie — ”

“Justin, you shall listen to me!” said the Duchess. “Of course I might have known you would find out — how did you, Monseigneur? It was very clever of you, I think. No, no, let me speak! — I meant that Dominique should not marry Mademoiselle Challoner. But now I have seen her, and I am not a fool, me, and she is a person entirely respectable, and this time I do not care what you may say, Dominique is to marry her.”

His grace looked down at her impassively. “Quite right, my dear. He is,” he said.

The Duchess opened her eyes very wide indeed. “You do not mind, Monseigneur?”

“I cannot conceive why I should be supposed to mind,” said his grace. “The marriage seems to be eminently desirable.”

The Duchess let go of Miss Challoner to fling out her hands. “But, Monseigneur, if you do not mind why did you not say so at once?” she demanded.

“You may perhaps recall, my love, that you forbade me to speak.”

The Duchess paid no attention to this, but said with her usual buoyancy: “Voyons, now I am quite happy!” She looked at Mary again. “And you — I think you will be very good to my son, n’est-ce pas?”

Miss Challoner said: “I love him, ma’am. I can only say that. And — and thank you — for your — ”

“Ah, bah!” Léonie said. “I do not want to be thanked. Where is Rupert? I must tell him at once that everything is arranged.”

Lord Rupert, who had evidently been detained outside, came into the room at this moment. He seemed preoccupied, and addressed himself at once to his brother. “Damme, Avon, I’m devilish glad you’ve come!” he said. “The Lord knows I never thought I should want to see you, but we’re in a plaguey difficulty.”

“No, we are not, Rupert!” Léonie told him. “It is all arranged.”

“Eh?” His lordship seemed surprised. “Who arranged it?”

“Oh, but Monseigneur, of course! They are to be married.”

Rupert said disgustedly: “Lord, can’t you think of aught beside that young fire-eater of yours?” He took hold of one of the silver buttons on his grace’s coat, and said confidentially: “It’s a mighty fortunate thing you’ve arrived, Avon, ’pon my soul it is. I’ve got six dozen of burgundy, and about three of as soft a port as ever I tasted, lying back in Dijon. I bought ’em off the landlord of some inn or another we stayed at, and the devil’s in it I can’t pay for ’em.”

“Monseigneur, I am quite ennuyée with this wine,” said Léonie, “Do not buy it! I do not wish to travel with bottles and bottles of wine.”

“May I request you to unhand me, Rupert?” said his grace. “If you have purchased port it must of course go by water. Did you bring a bottle with you?”

“Bring a bottle? Lord, I’ve brought six!” said Rupert. “We’ll crack one at once, and if you don’t find I’m right — well, you’ve changed, Justin, and that’s all there is to it.”

Léonie said indignantly: “Rupert, I do not care what you do, but I wish to present you to Mademoiselle Challoner, who is to marry Dominique.”

His lordship was roused to look round. “What, is she here?” He perceived Mary at last. “So you’re the girl that confounded nevvy of mine ran off with!” he said. “I wish you joy of him, my dear. A pretty dance you’ve led us. You’ll forgive me if I leave you at this present. There’s a little matter demanding my attention. Now, Avon, I’m with you.

Léonie called after him: “But Rupert, Rupert! Where are Juliana and M. Comyn?”

Rupert looked back from the doorway to say: They’ll be here soon enough. Too soon for my liking. Stap me if ever I saw such a pair for ogling and holding hands. It’s enough to turn a man’s stomach. Their chaise fell behind.”

He went out as he spoke, and Léonie turned to Miss Challoner with a gesture of resignation. “He is mad, you understand. You must not be offended with him, for presently he will recover, I assure you.”

“I could not be offended, ma’am,” said Miss Challoner. “He makes me want to laugh.” She moved a little away from the Duchess. “Madame, are you — are you sure that you wish me to marry your son?”

Léonie nodded. “But yes, I am quite sure, petite.” She sat down by the fire, and held out her hand. “Come, ma chère, you shall tell me all about it, please, and — I think, not cry, hein?”

Miss Challoner dabbed at her eyes. “No, ma’am, certainly not cry,” she said rather tremulously.

Ten minutes later Miss Marling came in to find her friend seated at the Duchess’s feet, with both her hands clasped in Léonie’s. She said brightly: “Oh, Aunt Léonie, is it all decided, then? Has my Uncle Justin given his consent? I vow it is famous!”

Léonie released Miss Challoner and stood up. “Yes, it is quite famous, as you say, Juliana, for now I am to have a daughter, which will amuse me very much, and Dominique is to make no more scandals. Where is M. Comyn? Do not tell me you have quarrelled again?”

“Good gracious, no!” replied Juliana, shocked. “Uncle Rupert met us in the hall, and he took Frederick off with him to that room over the way. I think they are all there. I am certain I saw Vidal.”

“Voyons, it is insupportable!” said her grace. “Do they all go off to drink Rupert’s wine? I won’t have it!”

She went quickly out into the hall with Miss Challoner, who followed in the direction of her accusingly levelled finger, and frankly laughed. Through the archway that gave on to the coffee-room the outraged Duchess could see her son, seated on the edge of a table with one foot swinging, and a glass in his hand. Lord Rupert was in the background, holding a bottle, and speaking to somebody outside Léonie’s range of vision. A burst of laughter set the seal to her grace’s wrath. She promptly walked into the coffee-room, saw that not only Mr. Comyn, but her husband also, was there, and said reproachfully: “But I find you extremely rude, all of you! One would say this wine of Rupert’s, of which I have already heard enough, was of more importance than the betrothal of Dominique. Ma fille, come here!”

Miss Challoner came and shook her head. “Dreadful, madam!” she said.

“Devil a bit!” said Lord Rupert. “We’re drinking your health, my dear.” He saw Vidal smile across at Miss Challoner, and raise his glass in a silent toast, and said hastily: “That’ll do, Vidal, that’ll do! Don’t start fondling, for the love of God, for I can’t bear it. Well, what d’ye say, Justin? Will you buy it or not?”

His grace sipped the wine, while Lord Rupert watched him anxiously. The Duke said: “Almost the only evidence of intelligence I find in you, Rupert, lies in your ability to pick a wine. Decidedly I will buy it.”

“Now that’s devilish good of you, ’pon my word it is!” said his lordship. “Damme, if I don’t let you have a dozen bottles of it!”

“Your generosity, my dear Rupert, quite overwhelms me,” said his grace with polite gratitude.

Léonie stared at his lordship. “Let Monseigneur — oh, but that is too much, enfin!”

“No, no,” replied his lordship recklessly. “He shall have a dozen: that’s fair enough. Give your mother a glass, Vidal — oh, and what’s the girl’s name? Sophia! Give her a glass too, for I’ve — ”

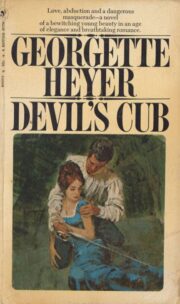

"Devil’s Cub" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Devil’s Cub". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Devil’s Cub" друзьям в соцсетях.