Her hand crept up surreptitiously under her cloak to feel the wound on her shoulder. The Marquis’s fine handkerchief was still knotted round it. She thought she would keep that handkerchief always, in memory of one brief moment when she had been sure that he loved her.

Tears stung her eyelids; she forced them back, casting a timid look round the coach to see whether anyone was looking at her. The stout woman was asleep, with her jaw sagging; two farmers were earnestly conversing opposite to her, and judging from his stertorous breathing she thought the man on her left was also asleep.

Well, that one moment’s conviction would comfort her in the lonely future. He had called her — but, after all, it was dangerous to recall his words, or the look on his face, or the gentle note in his voice.

She had thought — it seemed a long time ago now — that if only he had loved her she could marry him, but she had not considered then what it would mean to him to marry one so far beneath him. Perhaps his father would cast him off; it might even be in his power to disinherit him, and from all she had heard of his grace he was quite capable of doing that. She did not think that his love would survive exclusion from his own order, nor could she for an instant contemplate dragging him down to the society of lesser men. She thought, a little sadly, that she had seen too clearly how a man could sink to be able to cheat herself into supposing that the Marquis would maintain his position. Her own father had been disowned by his father, and he had ceased to associate with his old friends, because he had been looked at askance, as one who had committed the unforgivable sin. If the Duke of Avon had it in his power to disinherit his son, the Marquis would soon find himself condemned to the society of Miss Challoner, and Uncle Henry Simpkins, and their like. The very notion was so incredible that had her heart been less heavy she would have smiled at it.

It had grown dark inside the coach, and very chilly. Miss Challoner drew her cloak more tightly round her, and tried to ease her cramped limbs. It did not seem as though they would ever arrive at Pont-de-Moine. At every halt, of which there were many, she waited hopefully to be set down, but though one of the farmers had alighted, and two other persons entered the coach, no summons had yet come for her. She had no means of ascertaining the time, but she felt sure she had been travelling for many hours, and had begun to wonder whether the guard had forgotten her, and long passed Pont-de-Moine, when the coach stopped again before a well-lighted inn, and the door was pulled open.

The guard announced Pont-de-Moine in a stentorian voice which woke the fat woman with a jerk. The child, drowsing in her arms, set up a whimper, and Miss Challoner descended thankfully on to the road.

The guard, who apparently took a friendly interest in her, jerked his thumb towards the open door of the inn, and said that she had best bespeak a bed for the night there. She looked at the inn doubtfully, fearing from its well-kept appearance that it might be beyond her means to stay there, and inquired whether there was not some smaller hostelry to which she could repair.

The guard scratched his chin, and ran his eyes over her thoughtfully. “Not for you, there is not,” he said bluntly. “There’s only a tavern, at the end of the village, but it’s not fit for a decent woman to enter.”

Miss Challoner thanked him, and rather recklessly pressed a silver coin into his hand, thereby depleting her slender hoard still further.

She watched the guard climb on to the box again, and feeling somewhat as though she had lost her only friend in all France, she turned, and walked resolutely into the inn.

She found herself in a small well-hall, with the stairs running up to a couple of galleries on the first and second storeys. The place was lit by swinging lamps, and had several doors leading out of it on one side. On the other an archway afforded a glimpse of a comfortable coffee-room.

Out of this apartment the landlord came bustling, a lean man with a sharp face, and a habit of sniffing. He came bowing, and rubbing his dry hands together, but when he saw that his visitor was quite unattended, his manner changed, and he asked her in a curt way what she wanted.

She was unaccustomed to meet with incivility, and instinctively she stiffened. She replied in her quiet, well-bred voice, that she had alighted from the stage, and required a bed-chamber.

Like the guard, the landlord eyed her up and down, but in his glance was no friendliness, but a distinct look of contempt. Solitary females travelling by stage were not wont to put up at his inn, which was a house catering for the nobility and gentry. He asked warily whether her abigail was outside, with her baggage, and perceived at once, from her sudden flush and downcast eyes, that she had no abigail, and probably no baggage either.

Until this humiliating moment Miss Challoner had not considered her extremely barren state. She knew quite well in what a light she must appear, and it took all her resolution not to turn and run ignominiously away.

Her fingers clasped her reticule tightly. She lifted her head, and said calmly: “There has been an accident, and my baggage is unhappily left behind me at Dijon. I expect it to-morrow. Meanwhile I require a bed-chamber, and some supper. A bowl of broth in my room will suffice.”

It was quite evident that the landlord did not place any belief in the existence of Miss Challoner’s baggage. “You have come to the wrong inn,” he said. “There is a place down the street for the likes of you.”

He encountered a look from Miss Challoner’s fine grey eyes that made him suddenly nervous lest her story might after all be true. But at this moment he was reinforced by the arrival of his wife, a dame as stout as he was lean, who demanded to know what the young person wanted.

He repeated Miss Challoner’s story to her. The dame set her arms akimbo, and gave vent to a short bark of laughter. “A very likely tale,” she said. “You’d best be off to the Chat Griz, my girl. The Rayon d’Or does not honour persons of your quality. Baggage in Dijon indeed!”

It did not seem as though an appeal to this scornful lady would be of avail. Miss Challoner said steadily: “I find you impertinent, my good woman. I am English, travelling to rejoin my friends in the neighbourhood, and although I am aware that the loss of my baggage must appear strange to you — ”

“Vastly strange, mademoiselle, I assure you. The English are all mad, sans doute, but we have had many of them at the Rayon d’Or, and they are not so mad that they permit their ladies to journey alone on the diligence. Come, now, be off with you! There is no lodging for you here, I can tell you. Such a tale! If you are English, you will be some serving-maid, very likely dismissed for some fault. The Chat Griz will give you a bed.”

“The guard on the stage warned me what kind of a hostelry that is,” replied Miss Challoner. “If you doubt my story, let me tell you that my name is Challoner, and I have sufficient money at my disposal to pay for your bed-chamber.”

“Take your money elsewhere!” said the woman brusquely. “A nice thing it would be if we were to house young persons of your kind! Don’t stand there staring down your nose at me, my girl! Be off at once!”

A soft voice spoke from the stairway. “One moment, my good creature,” it said.

Miss Challoner looked up quickly. Down the stairs, very leisurely, was coming a tall gentleman dressed in a rich suit of black cloth with much silver lacing. He wore a powdered wig, and a patch at the corner of his rather thin mouth, and there was the hint of a diamond in the lace at his throat. He carried a long ebony cane in one hand, and a great square emerald glinted on one of his fingers. As he descended into the full light of the lamps Miss Challoner saw that he was old, although his eyes, directly surveying her from under their heavy lids, were remarkably keen. They were of a hard grey, and held a cynical gleam.

That he was a personage of considerable importance she at once guessed, for not only was the landlord bowing till his nose almost touched his knee, but the gentleman had in every languid movement the air of one born to command. He reached the foot of the stairs, and came slowly towards the group by the door. He did not seem to be aware of the landlord’s existence; he was looking at Miss Challoner, and it was to her and in English that he addressed himself. “You appear to be in some difficulty, madam. Pray let me know how I can serve you.”

She curtsied with pretty dignity. “Thank you, sir. All I require is a lodging for the night, but I believe I must not trouble you.”

“It does not seem to be an out-of-the-way demand,” said the gentleman, raising his brows. “You will no doubt inform me where the hitch lies.”

His air of calm authority brought a smile quivering to Miss Challoner’s lips. “I repeat, sir, you are very kind, but I beg you will not concern yourself with my stupid affairs.”

His cold glance rested on her with a kind of bored indifference that she found disconcerting, and oddly familiar. “My good child,” he said, with a touch of disdain in his voice, “your scruples, though most affecting, are quite needless. I imagine I might well be your grandfather.”

She coloured a little, and replied, with a frank look: “I beg your pardon, sir. Indeed, my scruples are only lest I should be thought to importune a stranger.”

“You edify me extremely,” he said. “Will you now have the goodness to inform me why this woman finds herself unable to supply you with a bed-chamber?”

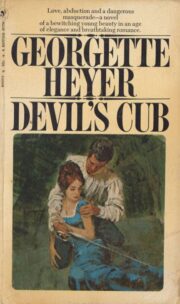

"Devil’s Cub" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Devil’s Cub". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Devil’s Cub" друзьям в соцсетях.