The landlord’s apologies and explanations were cut short by the somewhat tempestuous entrance of a copper-headed lady in a gown of green taffeta, and a cloak clutched round her by one small hand. “It is not at all deserted, because my son is here,” asserted this lady positively. “I told you we should find him, Rupert. Voyons, I am very glad we came to Dijon.”

“Well, he ain’t here so far as I can see,” replied his lordship. “Damme, ifI can make out what this fellow’s talking about!”

“Of course, he is here! I have seen his chaise! Tell me at once, you, where is the English monsieur?”

Miss Challoner’s hand stole to her cheek. This imperious and fascinating little lady must be my lord’s mother. She cast a glance about her for a way of escape, and seeing a door behind her, pushed it open, and stepped into what seemed to be some sort of a pantry.

The landlord was trying to explain that there were a great many English people in his house, all fighting duels or having hysterics. Miss Challoner heard Lord Rupert say: “What’s that? Fighting? Then I’ll lay my life Vidal is here! Well, I’m glad we’ve not come to this devilish out-of-the-way place for nothing, but if Vidal’s in that sort of a humour, Léonie, you’d best keep out of it.”

The Duchess’s response to this piece of advice was to demand to be taken immediately to her son, and the landlord, by now quite bewildered by the extremely odd people who had all chosen to visit his hostelry at the same time, threw up his hands in an eloquent gesture, and led the way to the private parlour.

Miss Challoner, straining her ears to catch what was said, heard Lord Vidal exclaim: “Thunder an’ Turf, it’s my mother! What, Rupert too? What the devil brings you here?”

Lord Rupert answered: “That’s rich, ’pon my soul it is!”

Then the Duchess’s voice broke in, disastrously clear and audible. “Dominique, where is that girl? Why did you run off with Juliana? What have you done with that other one whom I detest infinitely already? Mon fils, you must marry her, and I do not know what Monseigneur will say, but I am very sure that at last you have broken my heart. Oh, Dominique, I did not want you to wed such an one as that!”

Miss Challoner waited for no more. She slipped out of the pantry, and went through the coffee-room to the stairs. In her sunny bedchamber, looking out on to the street, she sank down on a chair by the window, trying to think how she could escape. She found that she was crying, and angrily brushed away the tears.

Outside, the Duchess’s chaise was being driven round to the stables, and a huge, lumbering coach, piled high with baggage, was standing under her window. The driver had mounted the box, but was leaning over to speak to a fat gentleman carrying a cloak-bag and a heavy coat. Miss Challoner started up, looked more closely at the coach, and ran to the door.

One of the abigails who had lately had her ear glued to the parlour door, was crossing the upper landing. Miss Challoner called to her to know what was the coach at the door. The abigail stared, and said she supposed it would be the diligence from Nice.

“Where does it go?” Miss Challoner asked, trembling with suppressed anxiety.

“Why, to Paris, bien sûr, madame,” replied the girl, and was surprised to see Miss Challoner dart back into her room. She emerged again in a few moments, her cloak caught hastily round her, her reticule, stuffed with her few belongings, on her arm, and hastened downstairs.

No one was in the coffee-room, and she went across it to the front door. The guard of the diligence had just swung himself up into his place, but when he saw Miss Challoner hailing him, he came down again, and asked her very civilly what she desired.

She desired a place in the coach. He ran an appraising eye over her as he said that this could be arranged, and asked whither she was bound.

“How much money is needed for me to travel as far as Paris?” Miss Challoner inquired, colouring faintly.

He named a sum which she knew to be beyond her slender means. Swallowing her pride, she told him what money she had at her disposal, and asked how far she could travel with it. The guard named, rather brutally, Pont-de-Moine, a town some twenty-five miles distant from Dijon. He added that she would have enough left in her purse to pay for a night’s lodging. She thanked him, and since at the moment she did not care where she went as long as she could escape from Dijon, she said that she would journey as far as Pont-de-Moine.

“We shall arrive before ten,” said the guard, apparently thinking this a matter for congratulation.

“Good heavens, not till ten o’clock?” exclaimed Miss Challoner, aghast at such slow progress.

“The diligence is a fast diligence,” said the guard offendedly. “It will be very good time. Where is your baggage, mademoiselle?”

When Miss Challoner confessed that she had none, he obviously thought her a very queer passenger, but he let down the steps for her to mount into the coach, and accepted the money she handed him.

In another minute the driver’s whip cracked, and the coach began to move ponderously forward over the cobbles. Miss Challoner heaved a sigh of relief, and squeezed herself into a place between a farmer smelling of garlic and a very fat woman with a child on her knee.

Chapter XVII

Upon the Duchess of Avon’s entry into the parlour, Vidal had come quickly towards her, and caught her in his arms. But her opening speech made him let her go, and the welcoming light in his eyes fled. His heavy frown, so rarely seen by her, descended on his brow. He stepped back from Léonie, and shot a scowling look at Lord Rupert. “Why did you bring my mother here?” he said. “Can you not keep from meddling, curse you?”

“Easily, never fear it!” retorted Rupert. “Fiend seize you, d’ye think I want to go chasing all over France for the pleasure of seeing you? Bring your mother? Lord, I’ve been begging and imploring her to come home ever since we started out! God bless my soul, is that young Comyn?” He put up his glass, and stared through it. “Now what the plague are you doing here?” he inquired.

Léonie put her hand on Vidal’s arm. “It is of no use to be enraged, mon enfant. You have done a great wickedness. Where is that girl?”

“If you are speaking of the lady who was Miss Challoner,” replied Vidal icily, “she is upstairs.”

Léonie said quickly: “WasMiss Challoner? You have married her? Oh, Dominique, no!”

“You are entirely in the right, madame. I have not married her. She is married to Comyn,” said his lordship bitterly.

The effect of this pronouncement on the Duchess was unexpected. She at once turned to Mr. Comyn, who was trying to put on his coat again as unobtrusively as possible, and caught his hand in both her own. “Voyons, I am so very glad! It is you who are Mr. Comyn? I hope you will be very happy, m’sieur. Oh, but very happy!”

Juliana gave a strangled cry at this. “How can you be so cruel, Aunt Léonie? He is betrothed to me!”

“Damme, if he’s betrothed to you how came you to go off with Vidal?” demanded Lord Rupert reasonably.

“I didn’t!” Juliana declared.

“I said it was not so!” said her grace triumphantly. “You see, Rupert!”

“No, I’ll be pinked if I do,” replied his lordship. “If it was Comyn you ran off with, why did you say you’d gone with Vidal, in that devilish silly note of yours?”

“I didn’t run off with Frederick! You don’t understand, Uncle Rupert.”

“Then whom in the fiend’s name did you run off with?” said his lordship.

“With Vidal — at least, I went with him, but of course I did not elope, if that is what you mean! I hate Vidal! I wouldn’t marry him for the world.”

“No, my girl, you’d not have the chance,” struck in the Marquis.

Léonie at last released Mr. Comyn’s hand, which all this time she had been warmly clasping. “Do not quarrel, mes enfants. I find all this very hard to understand. Please explain to me, one of you!”

“They’re all mad, every one of ’em,” said Rupert with conviction. He had put up his glass again, and was observing his nephew’s attire through it. “Blister it, the boy can’t spend one week without being in a fresh broil! Swords, eh? Well, I’m not saying that ain’t better than those barbarous pistols of yours, but why in thunder you must be for ever fighting. — Where’s the corpse?”

“Never mind about that!” interrupted Léonie impatiently. “I will have all of this explained to me at once!” She turned once more to Mr. Comyn, who had by now pulled on his boots and was feeling more able to face her. She smiled engagingly at him. “My son is in a very bad temper and Juliana is not at all sensible, so I shall ask you to tell me what has happened.”

Mr. Comyn bowed. “I shall be happy to oblige you, ma’am. In fact, when your grace entered this room, I was about to make a communication of a private nature to his lordship.”

Vidal, who had gone over to the fireplace, and was staring down into the red embers, lifted his head. “What is it you have to say to me?”

“My lord, it is a communication I should have desired to impart to you alone, but if you wish I will speak now.”

“Tell me and be done with it,” said my lord curtly, and resumed his study of the fire.

Mr. Comyn bowed again. “Very well, sir. I must first inform your lordship that when I had the honour of making Miss Challoner’s acquaintance at the house of Mme. de Charbonne in Paris — ”

Léonie had sat down in the armchair, but started up again. “Mon Dieu, the friend of Juliana! Why did I not perceive that that must be so?”

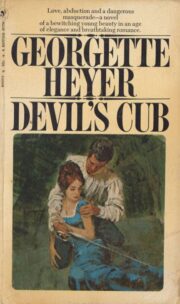

"Devil’s Cub" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Devil’s Cub". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Devil’s Cub" друзьям в соцсетях.