“I suppose you arranged as well for the vicar to be there, knowing he would be required?”

“Certainly I did. The marriage could not be performed without him. He went with Sir Harold. The solicitor also will be there, to see to the will.”

“Well, you have forgotten one rather important detail, milord. There have been no banns read, and we cannot be married without a license in that case!” she stated triumphantly.

“You are surely not under twenty-one?” he asked.

“I am twenty-two, but still a license is required, if I am not mistaken.”

“Only twenty-two? What a strong character you have, for one so young.”

“About the license…”

“I have a license, Miss Sommers. I took the precaution of procuring one two days ago, when Andrew first came down with pneumonia, in case it should be necessary in a hurry.”

“I daresay you have got a gold band in your pocket as well,” she said, resigned to his omniscience.

“Did you want a gold band in particular, ma’am? I have selected a rather pretty circlet of diamond baguettes. I hope I chose the right size.”

She hadn’t a doubt in the world he had. “My bridesmaid and best man?” she inquired, suppressing a fierce urge to giggle.

“Lady Jane and myself. You have no objection?”

“None in the least. Where are we to go for our honeymoon?”

“No honeymoon will be possible, I’m afraid,” he replied blandly. “But you are young yet. There is no saying you will not have a real marriage before too many years, if you are interested in it at all.”

“I will be sure to put you in charge of arranging all the details,” she said, then stopped short, as she realized what freedom she was taking with the almighty Lord deVigne.

“You couldn’t do better,” he answered readily. Offense, like humility and shame, was missing when she expected to see it. He spoke on calmly, as though they were out for a Sunday drive, no more. “There will be a good many bothersome details in this business. As I have coerced you into the match, I shall attend to them all, to give you as little worry as possible.”

“That is very kind of you, but I have been accustomed for many years to looking after myself, milord.”

“The experience has left its trace on you. I do not mean that as a criticism. Quite the contrary.”

“I would appreciate being consulted at least on any details that have a direct bearing on me.”

“I will bear it in mind, ma’am,” he agreed, nodding at her.

“I must notify Mr. Umpton I will not be at school tomorrow.”

“Or any other tomorrows.” What a pleasing phrase! A wave of complete exultation washed over her, to be at last free of Umpton and the students. He spoke on, apparently unaware of her feelings. “I understand Mr. Umpton’s cousin, a Mr. Perkins, is interested in the position. Shall I get in touch with Umpton?”

After her protest at independence, it was too cowardly to ask him to do it, yet it was the one chore she would happily have relegated to him.

“You will be busy, and in some state of perturbation as well in all the excitement. Let me do it for you,” he suggested, in a rather final tone that indicated the matter was settled.

“Thank you, if you would be so kind,” she said meekly.

Before it seemed possible, the carriage had climbed the hill, with the metallic table of glittering sea stretching below them, an incredible view really, but little appreciated today. They pulled up outside the half-timbered cottage where Mr. Grayshott lay ill. DeVigne looked at the unkempt yard and building, then glanced at his companion. “All this mess can be cleared away very easily,” he assured her.

Sir Harold’s coach was already there, and a gig belonging to the solicitor. It seemed less possible every moment for Delsie to retreat from her decision, to refuse to marry him. The so-much-wanted time for reconsidering did not exist. DeVigne ushered her into the house, where an unpleasant odor assailed her nostrils, but before she had time to look about her, she was being hurried upstairs, with a stream of chatter to divert her, to prevent her thinking about what lay ahead. They walked along an uncarpeted hallway, knocked at a closed door, and were bade to enter. Mr. Grayshott lay propped up on pillows in a handsome four-poster bed, with his valet bending over him. He had been prepared for the ceremony, with his tails of hair trimmed, his face shaven, and a dressing gown of peacock hues over his thin shoulders. Still, to his bride he looked like a caricature of his former self, with his face shrunken almost beyond recognition and turned to an alarming graying tone. Clearly there would be no recovering from such an advanced state of decline.

He held out a hand and said in a weak voice, “Come in, Miss Sommers.” She entered, reluctantly, and deVigne came beside her. “Leave us, Max. You too, Samson,” he said to his valet. Delsie cast one wild, imploring look to deVigne. His fingers tightened reassuringly on her arm before he left, with Samson departing from another door. She stood alone with her bridegroom.

“Come closer,” he said. She advanced to the side of the bed. He reached out a hand to her, and in confusion, she put hers into it. “Miss Sommers-now I may call you Delsie-at last it is to be.” He referred, she presumed, to their marriage. “You have made me wait too long,” he said sadly. “Still, you are mine at last, and we shall have a few months together at least.” Her heart fluttered at this grim forecast, but of course it was nonsense. He was at death’s door. Perhaps they had led him to believe it, to get his agreement to the marriage.

She half feared he might close his eyes and expire even while she stood with her hand in his. He sighed, but a stronger pressure from his fingers told her death was not yet at hand. “There is so much I would say,” he began, with his eyes closing. “You will be kind to my little Bobbie. I know that much. Promise me you will take care of her.”

“Yes, I promise.”

Again he squeezed her fingers, while she looked at the wizened face before her. “You will not regret it,” he went on, weakly. “The cottage and her mother’s portion are for my daughter. It was arranged by deVigne, but the rest of it is yours-payment for this favor you do me. There is money, you know. I have money.” He got his eyes open, with some effort, and looked at her closely.

“I do not do this for money,” she said. Grayshott’s fortune, she knew from deVigne, was dissipated.

“For love?” he asked, and smiled ironically. She said nothing. This was carrying hypocrisy too far. She could not say she loved him. He lifted the hand he held to his lips and kissed it, while she stood rigid with embarrassment and shame, and even anger. Then he fell into a fit of coughing. “Better get on with it,” he said when he had recovered. “Call deVigne.”

She was heartily glad to leave the room in search of him, and hadn’t far to go. He stood outside the door, a few feet down the corridor, with the vicar, Lady Jane, and Sir Harold, and no doubt the solicitor too was not far behind, though she didn’t actually see him. The whole party entered Grayshott’s room, except Sir Harold, who went below. The bride stood beside the prostrate bridegroom, and the vicar, opening his book, began to intone the solemn words of the marriage ceremony. How inappropriate they sounded-”to love, honor, and cherish…to have and to hold…till death us do part…” It was a moot point whether the groom would last out the ceremony. Grayshott held her hand tightly throughout the reading, repeating those portions of the service that ritual decreed. “I, Andrew Grayshott, take thee, Delsie Sommers…”

Best not to think. Think about something else. In five minutes it will be over-I can leave. Miss Frisk is having her lunch now. No school tomorrow, or any tomorrows. DeVigne is not wearing his good-luck charm today. I wish I were wearing it. I think I’m going to giggle-I think I’m going crazy. Where shall I go when this wedding is over? Do I remain here, in this house? No doubt deVigne has arranged all details.

She repeated her words, parrot-like, and soon the circlet of diamond baguettes was being pushed on to her finger by Andrew. It had the weight of a pair of manacles, and though it was pretty, she felt a strong urge to pull it off and throw it out the window. Then they were signing papers, people were shaking her hand-so foolish-the vicar wishing her happy. My God, what must he make of this travesty? What subtle pressures had deVigne brought to bear, to make him go through with it?

“Leave us now,” Grayshott said to them all. “I want to be alone with my bride.” Delsie cast a frightened glance to the little group, then looked to her groom. “Don’t worry, Max, you can send in the solicitor in five minutes. Leave me five minutes’ privacy with my wife,” Grayshott said, his voice fading.

They left, but the ceremony had tired Grayshott, and the five minutes were not so harrowing as she had feared. She sat beside him, while he held her hand, his eyes closed, his lips smiling. He looked frighteningly like a death mask. “Talk to me,” he ordered.

What did one say to a man at death’s door, a man, besides, whom one had just married without caring for him in the least? She decided to talk of his daughter. “I shall take good care of Roberta,” she began. “I shall try to be a mother to her. I am used to dealing with children. I am-was-a schoolteacher, you recall.” He nodded, satisfied apparently with this line, and she rambled on, making much of nothing.

After an interval that was surely at least five minutes, he opened his eyes and said, “You’ll do. There is money-I should tell you where. It’s not easy. I’ll tell you later, when I feel stouter. I saved it for you, for…” Then he fell into a coughing fit again, and it was clear he was nearly spent. There was a tap at the door. DeVigne entered, with the solicitor at his heels.

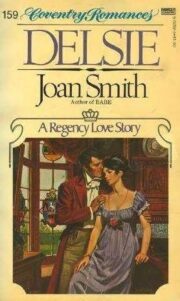

"Delsie" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Delsie". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Delsie" друзьям в соцсетях.