Awake now, she could not believe she wasn’t still dreaming. Impossible the pixies were back! Andrew was dead; the smuggling was finished, yet those sounds of voices, of jiggling harnesses and the clop of animals’ hooves, were clearly distinguishable. With a rush of anger she jumped out of bed and ran to the window. The caravan-there were at least five mules!-was entering the orchard. In the dim light of a new moon it was hard to see, but clearly the sides of the mules were disfigured with bulges-barrels of brandy. She peered hard to try to distinguish individuals-dark forms were visible, but no facial features. Then she saw one shape clearly different from the others-a large woman, wearing white. Mrs. Bristcombe, still wearing her white apron. She could not make a positive identification, but she was morally certain who that one person was.

Fear was forgotten in the first rash rush of anger. Her whole impulse was to run down to the orchard and order them away. But she had not lived most of her adult life in a seaside town without having heard tales of the behavior of smugglers, and her next thought was to bolt her door, jump into her bed, and pretend to be oblivious to the whole. In fact, she did this, but the racket continued with really very little effort at silence, till at length her fear lessened, and she began considering what she might do without endangering herself or the other innocent ones in the house.

She got out of bed, put on her gown, unbolted her door, and tiptoed down to Miss Milne’s room. Odd that Bobbie slept through the noise, she thought, but a glance into the room confirmed that the child was not awake. On to Miss Milne’s room, one door down. She entered softly and shook the sleeping form of the governess. What a sound sleeper she is, Delsie thought, and jiggled her arm harder. She had awakened more easily the other night-the falling shovel had awakened her. She began calling her name. For a full minute she indulged in this fruitless chore, till it was clear the girl was in no normal sleeping state, but was drugged. Who would have thought that nice Miss Milne took laudanum? It was impossible to rouse her. She wondered whether she had the courage to go above and try to awaken the girls from the Hall.

Then she thought again of Bobbie, sleeping like a top when she was a light sleeper. Was it possible she too was drugged? It was not long occurring to her what ailed them. It was the cocoa. They had all had it except herself, and Mrs. Bristcombe had insisted she have some too, to make sure they all slept through this latest smuggling expedition. Furious, she stood panting, while the full impotence of her position washed over her. She was in a house with no one she could alert, and outside the walls a band of villainous lawbreakers were piling up barrels of contraband in the orchard. She returned quietly to her room, determined to observe their every movement and discover, if she could, where the hiding place was. Tomorrow at the crack of dawn she would send for deVigne and place the mess in his lap, where it belonged.

The mules were being led out of the orchard when she resumed her post at the window, no longer bearing their felonious burden. Their sides did not bulge now. The men followed them, and two forms, the white-aproned one and another-the Bristcombes, of course-silently entered the house by the kitchen door. They hadn’t had time to do anything but place the barrels in the orchard, she figured. They had the impudence to leave their smuggled goods standing in plain view in her orchard. Her wrath knew no bounds, but she was helpless till morning. She must remain immured in the house, with the incriminating evidence waiting to be discovered by a revenue man or honest citizen who chanced by. It was infamous, and in her mind it was not her late husband so much as her husband’s brother-in-law who was held accountable for it.

Little sleep was possible in such a state of agitation as she had achieved, but in spite of this, she was awake at her old familiar hour of seven. She dashed immediately to the window. The trunks of the apple trees successfully concealed the barrels of brandy, but she knew they were there, a barrel ingeniously hidden behind each tree. Of that there was not a single doubt in her mind. She was still a little frightened to go alone, so went along to see if Bobbie or Miss Milne were up. The child slept, but the governess was dressed, just drawing a brush through her hair, while covering a yawn with the other hand.

“Oh, good morning, Mrs. Grayshott,” she said, jumping up at her mistress’s entrance at this unaccustomed hour. Her hands flew to her head, as though to hold it on. “I have such a headache this morning,” she said. “I don’t know why I should have, for I slept like a top. But with the worst dreams. I thought I was being dragged by a horse. Isn’t that absurd?”

“Not so absurd as you may think,” the widow answered, and, carefully closing the door behind her, she went further into the room.

“What do you mean, ma’am?” the governess asked.

“There is something very odd going on here,” Delsie replied.

“Yes, I know. It is something to do with the orchard, isn’t it?”

“Have you heard something, Miss Milne?”

“Only rumors, ma’am. I don’t get into Questnow much myself, but my cousin Betsy at the Dower House made an odd remark when I was there Sunday. I told her about what happened to you the night we saw the man in the garden. I told her about the noises that happen there from time to time as well, and she said she thought maybe it was smugglers.”

“I think so myself, but it has gone beyond smugglers in the orchard. Miss Milne, I think you were drugged last night.”

The girl’s eyes opened wider in fright. It was not necessary to ask whether she had administered any laudanum to herself. She was horrified. “How should it be possible?”

“How indeed? You will remember the cocoa you drank. Bobbie, as well, slept like a top through the most infernal racket.”

“What about yourself, ma’am? You had cocoa too.”

“No, I didn’t drink it. I heard men in the orchard last night, and tried to rouse you. You were in a deep, drugged sleep. I watched from the window, and saw them bring a load of brandy into the orchard. I mean to go down this minute and see if I’m not right.”

“Folks do say it’s better not to meddle with the gentlemen,” the girl suggested, reluctant to comply with the hint.

“Very well, then, I shall go alone. It is broad daylight. I don’t suppose anything will happen to me.”

“You daren’t… I’ll go with you,” Miss Milne decided, snatching up a shawl.

They went silently along the hall, down the stairs, and out the front door, opening and closing it with caution to avoid alerting the Bristcombes. Quietly they hastened around the corner to the orchard, there to stare at each other in speechless amazement. There was no sign of a barrel, nor of any disturbance. “I know they were here. I saw them with my own eyes,” Delsie declared in frustration. She performed the futile gesture of darting to the back of the orchard, to see the rank grass untouched, its dew undisturbed, not a blade trampled down. “They were here. I am not mad!” she insisted to the doubting governess, regarding her questioningly.

“I had terrible dreams myself last night,” Miss Milne offered.

“Yes, because you were drugged,” Delsie stated firmly, with no outward show of wavering, though she was beginning to wonder if she had suffered a nightmare. “There is no point standing here arguing. I’ll speak to Mrs. Bristcombe about it.”

“Oh, Mrs. Grayshott, I wouldn’t!” Miss Milne warned.

“Am I to cower from my own housekeeper?” she answered indignantly.

“If you think she’s one of them… The tales Betsy told me of the village…”

“Yes, including the tale that is rampant there about me! My own students afraid to come to me because of the stories. It can’t go on. I’ll have this out with Mrs. Bristcombe.”

But when the steely-eyed Mrs. Bristcombe stood before her at breakfast, her nerve weakened. Not in front of the child, she excused her cowardice. I’ll speak to her later. “Did you sleep well?” the housekeeper asked, with a sly look on her face.

The gall of the question was sufficient to renew her fortitude. “No, I did not, Mrs. Bristcombe. Kind of you to ask. I slept very poorly, due to the disturbance in the orchard. I noticed from my window that you were present, and would like you to tell me what was going forward there.”

“Me?” the woman asked, with an amused grin on her wide face. “I was tucked up in my bed at nine o’clock, Mrs. Grayshott.”

“Not quite at nine, I think. You were kind enough to insist on making me a cup of cocoa at nine-thirty, if you will recall.”

“Oh, well, it may have been ten,” was the saucy answer, with a look that said, “Make what you can of that, milady.”

“Then again, it may have been two,” the widow replied frostily. She was suddenly aware of her vulnerable position. She and Miss Milne, who sat looking very much like a frightened bunny, and a child, were alone in the house with the Bristcombes. This powerful pair, allied as they were with the criminal smugglers-who could know what they might do? To delay bringing the matter to a crisis, she said, “I shall speak to Lord deVigne about it.”

I should fire her now, she thought, but was afraid. Her insides were shaking like a blancmange. She was cowering before her own housekeeper, as she had vowed she would not. But before the day was out, she would be rid of this woman and her husband.

“I’ll just see if Mr. Bristcombe knows what you’re talking about,” the housekeeper said. Her manner became more compliant at the mention of deVigne’s name. They did not fear herself, a defenseless widow, but they were still not intrepid enough to take on the lord of the village.

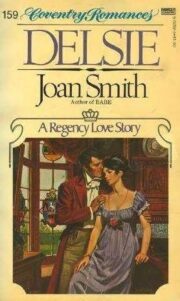

"Delsie" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Delsie". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Delsie" друзьям в соцсетях.