“I have been looking for an excuse to get into Andrew’s cellars,” deVigne claimed. “If he has a hogshead of that brandy you like to throw on the fire, I shall take it as my fee for looking for gold.”

“Agreed!” Mrs. Grayshott declared. “And it was you who threw it on the fire,” she added.

“Brandy will not put out a fire,” Sir Harold informed them.

His spouse repressed the urge to tell him to shut up, and said instead, “It is odd finding one of the bags in Louise’s desk. Do you think she put it there? That Andrew has been acting this way for so long?”

‘There is no way we shall discover it now,” her nephew replied.

“Is it possible he had more money that you knew?” Delsie asked. “You mentioned he lost a good deal in poor investments, but might he not have kept some cash on hand, in the house?”

“I can’t think so. He was eager to get his hands on Louise’s settlement in cash, and told me at the time he was in tight waters financially. That was three years ago, more or less, for he went through his roll very quickly after Louise died. Went on a big binge of selling everything. In fact, he sold his own yacht to settle some accounts. You recall he had kept the Robert-Lou for his own use, Jane?” deVigne asked.

“Yes. When he sold out to Blewes, he kept the smallest ship and fitted it up for a pleasure craft. Too big, of course, and I don’t believe he had it out above two or three times. It was foolish to keep it. Well, it required a crew of six or seven men, and Andrew himself never was much of a sailor. It was a sentimental gesture, keeping it and naming it for his wife and daughter. He sold it to some fellow in Merton, I think.”

“His own uncle took it off his hands. Old Clancy it is who has the Robert-Lou,” Sir Harold told them.

“I wish I could remember…” Delsie said, staring into the leaping flames. Everyone looked at her to hear an explanation of this pregnant statement. She went on: “During those few very brief conversations I had with Mr. Grayshott, just before and after the ceremony, he talked about money.”

“I made sure he was wooing you,” Lady Jane laughed.

“No, he asked me to take good care of Roberta, then said something to the effect that I would be rewarded for it. He mentioned that Louise’s portion and the Cottage were for Bobbie, but said he had some money-something of the sort.”

“His personal effects were left to you-in fact, in the will the wording is that his estate entire is bequeathed to his wife,” deVigne outlined. “It is no fortune-some few pieces of jewelry, his horses and carriages, his patents, which I think he still, at the end, believed might be worth something.”

“The spit was a clever idea,” Lady Jane suggested.

“For some people still use a dog in a wheel to turn the spit, you know, and it is disgusting to think of having a dirty old dog in the kitchen.”

“He never could peddle the hundred or so he made up,” deVigne reminded her. “About the horses and carriages, cousin, you would be well advised to sell them. I don’t hesitate to make the suggestion, as the hunters are a man’s high-bred goers, and the sporting carriage is an extremely precarious high-perch phaeton.”

“Yes, and the traveling carriage is a great lumbering coach a hundred or so years old, not useful at all,” Lady Jane added. “Every strap on it would break if anyone sat inside, I am convinced.”

“What happened to Louise’s silver, the art collection, all that fine furniture?” Sir Harold demanded petulantly.

“That was all gone years ago, my dear,” his wife told him, with scanty patience. She had listened to him rant for two months when the sale had taken place.

“Andrew used to have a fine residence in Merton,” deVigne explained aside to his widow. “The Cottage was never intended for more than a summer residence, to allow them to bring their family home and still have some privacy. Andrew and I never did rub along very congenially, as I originally made some efforts to dissuade her from accepting him. The Merton place was sold off some years ago.”

“You think these bags of gold I keep finding come after that date, then?”

“It is difficult to believe Andrew would have parted with his patrimony-and his yacht, which he loved-if he had had a fortune sitting around in gold. It must have been acquired since that time.”

“He was into some illegal business. That is the only explanation,” Sir Harold assured them. “Never liked the fellow above half. Don’t see why you let your sister have him, Max.”

“He seemed a rising young gent at the time. The best of a bad lot, for some of his family are hardly presentable. As to letting Louise do anything, you forget, Harold, what a hothead she was. She paid very little attention to the commands of a younger brother, and with her fortune in her own hands, she would have certainly dashed off and married him if I had forbidden the match.”

“Give the devil his due, he made Louise a good husband. Till her death he was a proper gentleman,” Jane reminded them. “It was losing her, so devoted to her as he was, that turned him to drink, and the drink accounts for the rest of it. Well, the drink and lack of breeding, for a real gentleman would not have gone to pieces only at losing a wife.”

“He was beginning to drink pretty heavily before Louise’s death,” deVigne mentioned, “but she kept him under some control.”

“So no one knows how to account for the gold?” Mrs. Grayshott asked, to call them back to order.

No one had a sensible suggestion on the subject, so they turned to other topics, deVigne to inquire of Mrs. Grayshott whether she had contacted the village girls, and what she would like done with the carriages and horses. It was agreed he would take them to auction, and suggested that he would be happy to look about for some replacement more suitable to a lady’s needs. Lady Jane was caught by her husband to hear a lengthy exposition of the many historical atrocities committed in the lust for gold. To escape him, she asked Delsie how the governess performed her duties.

“She is an excellent girl, well informed and conscientious. I enjoy her company, but to cut expenses I had thought I might teach Bobbie myself. It would be one less servant to pay, and I am qualified to undertake her training.”

“Oh, my dear, don’t think of it!” Jane expostulated at once. “If you haven’t someone to look after Bobbie, you will have a child on your hands twenty-four hours a day. You would be tied leg and wing, not a minute free to receive callers or to make a call yourself, or to come to us in the evenings, for you would not want to leave her in Mrs. Bristcombe’s charge, I am convinced. She would frighten the child with her stories of pixies and other superstitious ignorance. You cannot dispense with a woman of some sort to look after the child.”

These disadvantages had already occurred to the widow. She was fond of Roberta, but knew as well that a lady in her new circumstances was not saddled full-time with her children. “The reason I married Mr. Grayshott was to look after Roberta,” she reminded them.

“You are looking after her,” deVigne added his protest. “You are her legal guardian, and taking your job of husbanding her monies very seriously, but it is nonsense to speak of dispensing with a governess. As you settle into a more regular sort of a life here, you will find you haven’t time to devote your whole day to the child. That was never our intention. Even as a schoolmistress, you were not on duty twenty-four hours a day. I will risk giving you an unsolicited piece of advice. Keep the governess if you feel she is competent, and replace her if you feel otherwise. How does Bobbie like her?”

“They are on good terms, but…”

“Keep her, then,” Jane said conclusively. “Besides, I am the one who got Miss Milne the position, and she needs it. The father is dead, and there are three girls at home. It would be cruel to turn her off for no reason.”

This cunning fabrication, making an unexceptionable reason for Mrs. Grayshott to retain the girl, succeeded very well. There was no more talk of being rid of Miss Milne.

Dinner was called, and a peaceful evening was wiled away over a few hands of whist. As Mrs. Grayshott put on her bonnet and pelisse to leave, Lady Jane reminded her they would have a treasure hunt on the morrow, the details to be set up after church the next morning. When deVigne drove Delsie home to the Cottage, he inquired into her statement that Andrew had said he had money-had he specified in what form, or how much, or where?”

“No, it was very odd. I thought so at the time, and attributed it to his weak condition. He just said he had some money, that he had saved it-I don’t recall exactly, I was so confused myself. I think he was trying to tell me where it was, when you came in.”

“This must be what he meant, the bags of guineas. Perhaps he received some small inheritance from a relative. I heard nothing of it, but it is possible, in which case the mysterious bags of guineas are your own. He left his estate to you.”

“I have the sinking apprehension they were not bequeathed to him by any kindly relative. I think Sir Harold is right, and he was involved in some illegal business. Am I in any way responsible for my husband’s crimes in the eyes of the law, I wonder?”

“Don’t be foolish, cousin. If your husband was indeed participating in anything illegal, it has nothing to do with you.”

“Receiving stolen money has to do with me. Why, I am no less than an accessory after the fact. I shall end up in the stocks, with my former pupils pelting stones at me.”

“This is absurd,” he said brusquely. “It was all done before your time, and without your knowledge. There is no way it can possibly involve you.”

“Fine talk, but you are not a lawyer. I daresay I shall have need of one before this mess is settled.”

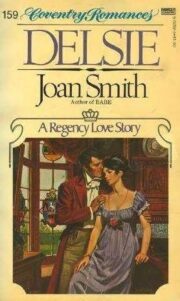

"Delsie" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Delsie". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Delsie" друзьям в соцсетях.