She was just turning to leave when her eye fell on a small canvas bag. Thinking she had discovered some clue left by the intruders, she picked it up with great curiosity. It was heavy and jingled with pieces of metal. Opening it, she was stunned to see it held a quantity of guineas. Bobbie was off throwing apples at a tree. Delsie decided to keep her discovery a secret from the child. She concealed it under her pelisse, but was highly curious to get to her room and count the guineas. What could account for it? What sort of intruders came and took nothing, so far as she could see, but left a bag of gold worth a great deal?

“Shall we pick some of these pretty ox-eye daisies and corn marigolds before we go in?” she asked. Together they went to the orchard’s edge to gather these late-blooming wildflowers, before going inside for breakfast. They took them to their rooms to arrange in a vase. Once she achieved privacy, Delsie emptied the canvas bag on the counterpane, marveling at the quantity of gold pieces-one hundred in all. One hundred gold guineas-more than a year’s salary. Her first inclination was to run to deVigne with the bag and ask his opinion, but Lady Jane was coming to call for her soon, and it would have to wait till after the shopping trip.

Afraid to leave such a fortune in her room, where she was by no means sure it would be safe from prying eyes after her departure, she put it in her reticule and took it to the table with her. Miss Milne and Bobbie soon joined her. The three were in no hurry to dispatch their breakfast, but could not make it last till nine-thirty, at which time Lady Jane was to arrive. Bobbie was taken, unwilling, to the schoolroom for a lesson, while Mrs. Grayshott sat going over her list, adding a new item at every spot where her eye fell. Beeswax and turpentine to remove the dust and grime from the saloon, more candles, a great deal of them as the house was so gloomy, embroidery woolens, and backing for her tambour frame. The items wanted seemed endless. She was still busy at this chore when the knocker sounded. As Bristcombe was still invisible, she went herself to answer it. DeVigne stood at the door, his carriage waiting on the roadside.

“Good morning, cousin,” he said brightly. “Still playing butler, I see. Did you speak to Bristcombe about leaving lights burning for you at night?”

“No, I spoke to his wife-but I never see him. I’m not sure I want to. Come in.”

“He was in the orchard just now as I came along the road. I made sure you had set him to gather the withered apples. They won’t be good for anything but pig feed, but I know your aversion to waste.”

“I must speak to you,” she said, ignoring this banter. She took him to the saloon, with a question as to why it was himself who had come in lieu of Lady Jane.

“We are to meet her in the village. With five of us, one carriage will not hold all your purchases on the return voyage, if you are the enthusiastic shopper most ladies are. I have business there, and shall bring Sir Harold back with me, leaving you three ladies to shop to your hearts’ content. But surely that is not what you meant to ask me. From the size of your eyes, I hoped for missing knives or forks at the least.”

“Nothing is missing,” she said with an air of vast importance. “Au contraire.”

“You have found the vanishing linens?” he asked, taking up a seat on the sofa.

“Nothing so paltry. I have found a bag of gold!” she announced.

“Congratulations. Was it a large bag of gold?”

She fished it out from the bottom of her reticule and handed it to him. “It is one hundred guineas!” she said importantly.

‘That should take care of the butcher,” he said, hefting the bag, and shaking a couple of pieces out into his hand. “They seem genuine. Where did you find them?”

“You will think it incredible, but it’s true! I found them under an apple tree in the orchard this morning. What can it mean?”

He looked at her, not at all so impressed as she had thought he would be with her find. “There haven’t been any rainbows lately, so that cannot account for it-the pot of gold.”

“Do be serious!”

“Perhaps Andrew, in one of those drunken ambulations you spoke of, dropped it one night, though I still can’t credit he ever left the house, with Samson and Bristcombe here to watch him.”

“They would not let him take so much money out with him in any case. What should I do? Ought I to advertise it, do you think? Oh, and I forgot to tell you, I know where it came from.”

“An advertisement seems superfluous in that case,” he suggested.

“Well it is not, because I don’t know who was there, but someone was in the orchard last night very late, with a horse or horses. At least two men. I heard them talking.”

“After you returned from the Hall?”

“Much later-not long before one o’clock, I think. I made sure it was only someone stealing the apples, and hardly gave it a thought, till I went into the orchard this morning and saw how far the fruit had deteriorated. Besides, it stands to reason anyone reduced to stealing half-rotten apples would not have a hundred guineas to lose.”

“Are you quite sure you heard someone?”

“Absolutely. I am not at all imaginative. Bobbie heard them too. She thought it was the pixies.” She sat thinking about it, then went on. “So it seems the pixies she was told about were not her papa in a drunken stupor after all. And that, you know, was the reason I held to account for her being put on the west side of the house, so she would not hear her father ranting about. DeVigne, is it possible there has been someone coming regularly into the orchard for years, ever since Bobbie was removed from the nursery? Only think, if they have been leaving bags of guineas for all that time, there must be a fortune about the house somewhere. I shall institute a search the moment I get back from the village,”

“You do rather leap to conclusions. Still, it is mighty curious. In the orchard, eh? Let’s have a look.”

“It’s no good. I went out bright and early, and couldn’t find a single thing, except the bag of gold, that is. But what shall I do about it? I cannot keep it.”

“Keep it for the time being. If it was lost by any innocent person, he won’t be long coming to look for it.”

“The horrid thought raises its head that innocent persons do not lurk about gardens and orchards that do not belong to them, carrying large sums of money. It must have been a criminal, and I know he will come back for it too. Have you heard any account of a robbery in the neighborhood?”

“No, nor can I conceive of any reason he should be in your orchard. Still, I’ll inquire in the village this morning-discreetly. It will be best to keep this to ourselves.”

“You do think there’s something odd going on, don’t you? Oh, what have you gotten me into?” she worried, wringing her hands.

“To date, the worst I have gotten you into is a bag of gold guineas. That should merit gratitude, not a scold. The only inconvenience to yourself has been a night’s disturbed sleep. You make too much of it, cousin.”

“Yes, a bag of gold belonging to some cutthroat burglar or smuggler, who will doubtless come after it in the night with a knife between his teeth. A mere bagatelle. I can’t imagine why I tremble every time I think of it. I must put them somewhere for safekeeping. Will you take charge of them for me?”

“Not at all imaginative, you say?” he asked, with a quizzing smile. “The knife between the teeth, surely…” She stuffed the bag into his hands, for he had placed it on the sofa between them after examining it. “There is a vault in the study. Let us put it there for the present.”

When they went to this room, there was no key in the vault, so deVigne carried the money into town, in a pocket of his carriage. This was done surreptitiously to keep it from Bobbie, who went with them. The child regaled her uncle along the way with the story of the pixies, while the widow stared at him with an “I told you so” look.

Delsie felt very much like a princess from a fairy tale when she first wafted into the village inside the crested carriage, with every head turning toward it. The carriage stopped outside the Venetian Drapery Shoppe, the one good store in the village. It was frequented only by the gentry, as the articles within and, more particularly, their prices were beyond the range of mere working mortals. Delsie had occasionally entered to buy a bit of lace or ribbon, and to admire the larger items. Her real purchases were made at Bolton’s, a less-elevated emporium across the street. She always felt she was encroaching to enter the former establishment. On her few forays, the salesman had looked down his nose at her and demanded in a supercilious tone if she wanted anything, or was “just looking.” Today the same toplofty person was bowing and simpering, for deVigne had said at the carriage he would just step in with her and Bobbie and wait till Jane arrived.

“Mrs. Grayshott will be opening an account here. Will you see she is taken care of?” was all he said. It was enough to set the clerk fawning on her in a manner that was every bit as jarring as his former neglect. His compliant voice was at her shoulder, pointing out a fine bit of imported lace, calling her attention to other wares. She was happy when Lady Jane arrived and told him they would take care of themselves. DeVigne then took his leave, and the two dames got down to rooting through the store in good earnest. They wanted first to obtain Bobbie’s materials, as the child was pestering them on this point.

Lady Jane, an inveterate bargain-hunter, complained about the price of everything, in no low tone, and indeed her complaints seemed well taken. For the honor of residing on the shelves of the Venetian Drapery Shoppe instead of Bolton’s, muslin was doubled in price. It was hastily decided between them that the more mundane purchases would wait for Bolton’s, and only the luxuries be purchased here. And what luxuries there were! Silk stockings, the finest of crepes and velvets for gowns, laces, ribbons and buttons of unimagined splendor, every one a jewel. With Bobbie’s materials selected, Delsie began the joyful chore of choosing her own. She had intended having three new gowns made up for her role as Mrs. Grayshott, but, with such a display of exotic goods before her, she could not limit herself to less than four-two afternoon outfits and two gowns for evening. The selection of accessories for the gowns too was pure pleasure. Mechlin lace, mother-of-pearl buttons, ribbons so narrow and dainty, a bottle of black bugle beads to decorate her finest gown. She began to wonder how they would transport all the purchases to the carriage, but discovered, before she exposed her ignorance, that they would be picked up by a footboy.

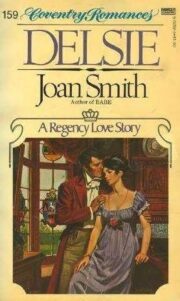

"Delsie" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Delsie". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Delsie" друзьям в соцсетях.