She had been married on Sunday. The funeral was Thursday. On Friday the idyll was over. DeVigne came over after breakfast to take her to the Cottage, her new home. “I’ll tell Miss Milne to prepare Bobbie’s things,” she said, and excused herself.

“I’m sorry to see them go,” Lady Jane said to her nephew. “It was good to have a spot of company. Harold is as dumb as a dog, unless I let him talk my ear off about Rome or Greece. It was a wise move, Max, to push this marriage.”

“It seems to be working out very well for us. I can’t imagine Mrs. Grayshott will be as happy at the Cottage as she has been here with you.”

“How happy can she have been in Questnow? What a strange, lonely life the girl has led. Little things she says betray her, you know, like how pleasant it is to have company for her meals. She must have eaten all alone, I suppose, since her mama’s passing. Imagine that ninny of a Harold having known Strothingham all along and not telling us. We might have made her acquaintance years ago.”

“She was living in a very mean sort of an apartment. Remarkable she is so refined.”

“I was happily surprised with her liveliness. I had not suspected vivacity from her, for she was such a dowdy little dresser, but she is very conversable. I like her excessively.”

The widow soon returned below with Bobbie and Miss Milne, the three of them to be taken in deVigne’s carriage to the Cottage. Once there, he did no more than make her acquainted with her housekeeper before leaving, saying he would return later in the day.

“You will find plenty to keep you busy,” he said, glancing around at the somber surroundings. “But I shan’t volunteer any suggestions, knowing you like to make your own decisions.” This was said in a rallying tone, but it did not rally her. She felt utterly depressed, and the large beef-faced woman standing before her in a soiled apron did nothing to cheer her up.

“I’ll take my leave now, Mrs. Grayshott,” deVigne bowed, and went to the door. Delsie looked helplessly to the governess and Bobbie, fast disappearing up the stairs, then after deVigne. She took a step after him, wishing she could run right out the door and go back to the Dower House. As she realized what she had done, she continued after him, as though, it had been her intention to accompany him to the front door.

“Don’t despair,” he said in a kindly tone. “This was used to be a fine and attractive home a few years ago, when my sister was alive. You will make it so again in a very short time, I am convinced. Be firm with the Bristcombes. They have fallen into slovenly habits with Andrew not watching them as he ought.” Mrs. Bristcombe stood with her arms crossed, staring at them suspiciously, beyond earshot. Then deVigne was gone, and Delsie turned back to face her future.

Be firm, he had said, and firmness was clearly needed here. “Have you any orders, miss?” Mrs. Bristcombe asked, an insolent expression settling on her coarse features as soon as deVigne was gone.

“Yes, the title is ma’am, not miss,” Delsie said in her firmest teacher’s voice, “and I shall have a great many orders. The first is that you put on a clean apron, and not wear a soiled one in my house again.”

“They don’t stay clean long in the kitchen,” the woman replied tartly, scanning her new mistress from head to toe in a very bold fashion. She had not behaved so when deVigne was with them.

“Then you must have several, to provide yourself a change, must you not?”

“Muslin costs money.”

“All of three shillings a yard, for that quality. I shall buy some, and you will have it made into aprons.”

Mrs. Bristcombe’s steely eyes narrowed, but she pulled in her horns. “What’ll you have for lunch?” she asked.

“What have you got in the house?”

“There’s cold mutton, and a long bill overdue at the grocer’s, while we’re on the subject.”

“Why has it not been paid?”

“The master’s been sick, as you might have heard,” she replied with a heavy sarcasm, to reveal her opinion of the marriage.

“Prepare your accounts and present them to me in the study this afternoon, if you please. The mutton will do for luncheon, with an omelette. You know how to prepare an omelette?” Delsie asked, to retaliate for the former insult.

The woman sniffed, and Mrs. Grayshott continued asserting her authority. “I am going to make a tour of the house. There is no need for you to accompany me. Miss Roberta will come with me.”

“You won’t find it in very good shape.”

“So I assumed,” Delsie replied, looking around her. “I understood girls were sent down from the Hall to tidy the place up.”

“They’ve changed the linen upstairs and cleaned up the yellow guest room for you.”

“Thank you, but I am not a guest in this house, Mrs. Bristcombe. I shall notify you what chamber I wish cleaned for me. Good day.” She turned and swept up the stairs, resolved not to let that Tartar get the upper hand of her, though she was weak from nervousness after the encounter.

She walked along the upstairs hall till she heard voices. Bobbie and Miss Milne were putting off their pelisses, and she requested Bobbie to show her around the house. “I’ll show you my room first,” Bobbie said proudly. “This is it.”

“I thought you would still be in the nursery,” Delsie answered. The room was not unpleasant, but it was not a child’s room. The furnishings were of dark oak, the window hangings and canopy of a somber, dusky blue. The paintings on the walls were also dark and not likely to appeal to a child.

“I wondered when I came that she was not in the nursery,” Miss Milne mentioned, “but I was told this is her room.”

“Mrs. Bristcombe told you?” Mrs. Grayshott inquired, in a voice a little taut.

“Yes, ma’am. I took my directions from her. I seldom spoke to Mr. Grayshott.”

“I had to leave the nursery last year, ‘cause I couldn’t sleep with all the noise,” Bobbie told them. Delsie thought this referred to noises made by a drunken father, and asked no more questions, but the child spoke on. “Mrs. Bristcombe said it was the pixies in the orchard,” she said, her eyes big. “Daddy said it was the pixies too, so I got this nice room, like a grown-up.”

“In the orchard?” Delsie asked, surprised that Mr. Grayshott would be allowed out of the house drunk. One would have thought his valet or Bristcombe would have kept him in. She must ask Lady Jane about this.

“I have thought I heard noises outside myself, from time to time,” Miss Milne said, rather hesitantly, as though she were unsure whether she should speak. “If you won’t be needing me right away, ma’am, I’ll go to my room and unpack.”

“Go ahead.” The girl left, with a rather shy smile. She would make a friend. It was a good feeling, to have one person of her own age and sex in the house, one not too far removed from her in breeding as well. The girl seemed polite and well behaved. Her chief interest, however, was in her new stepdaughter, and she turned to her with a determined smile. “How about showing me that walking doll you spoke of? I never heard of a doll who can walk. Do we have to hold her hands and pull her along?”

“Oh, no, she walks all by herself,” Bobbie boasted. “Daddy made her for me. Well, he didn’t ‘zactly make her. He bought a plain doll, and Mommy cut her stomach open, and Daddy put in some little wheels, and now she can walk.” As she spoke she went to a shelf where a considerable quantity of stuffed toys were set out, the only concession to the room’s being inhabited by a child. “Daddy was very smart, before Mommy died. He made a secret drawer in Mommy’s dresser that opens with a hidden button.”

She selected a doll dressed in a sailor’s uniform, reached under the jacket to wind a key, and, when the doll was set on the floor, it took half a dozen jerky steps before toppling over. “He doesn’t walk too good,” Bobbie said, setting it back up for another dozen steps.

“How ingenious! Your daddy made this?” Delsie asked, sure the child was inventing this story. But when she took the doll up, she saw that the stuffed body had indeed been slit open and sewed up.

“He made me a cat that shook her head too, but I broke her,” Bobbie said, then took the doll to throw it on the bed. “Next I’ll show you Mama’s room. It’s the nicest one. I think you should use it, only it’s quite far away from mine.”

They walked half the length of the hall, then Bobbie opened a door into a lady’s chamber of considerable elegance, though the elegance had begun to fade. It was done in rose velvet, the window and bed hangings still in good repair, but very likely full of dust. The furniture was dainty French in design, white-painted, with gilt trim. There was a makeup table with lamps, an escritoire-such a room as Delsie had only dreamed of. The late Mrs. Grayshott’s belongings were still laid out-chased-silver brushes, cut-glass perfume bottles, and a whole battery of pots and trays holding creams, powders, and the accessories to a lady’s toilette. “Let us see the yellow room Mrs. Bristcombe made up for me,” Delsie said, with a last, longing look at this room.

“It’s this way, next to mine,” Bobbie told her, and led her to a good room, square, but with none of the finery of the lady’s chamber. Like Bobbie’s, it faced the west side of the house, away from the orchard. “You won’t be bothered by the pixies either,” Bobbie told her.

“Likely that’s why she put you here. Miss Milne sleeps right next door.”

They did not disturb Miss Milne, but went along to look into other chambers, the master bedroom (which opened through an adjoining door into the late Mrs. Grayshott’s suite) being the end of the tour.

“Since you’re my mama now, I think you should sleep in here,” Bobbie said firmly.

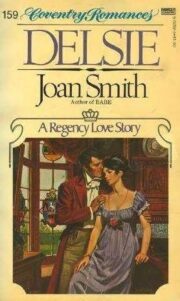

"Delsie" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Delsie". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Delsie" друзьям в соцсетях.