Perhaps all would right itself when Georgie was back with his mother. Louisa would be travelling with him tomorrow and it had been arranged that she and the baby were to go by chaise to the King’s Arms at Lambton, from where they would travel post to Birmingham where Sarah’s husband, Michael Simpkins, would meet them to drive home in his trap and Louisa would return to Pemberley by post the same day. Life would be easier for his wife and Will when the baby had been taken home, but when he returned to the cottage on Sunday after helping to put the house to rights after the ball, it would be strange not to see Georgie’s chubby hands held out in welcome.

These troubled thoughts had not prevented him from continuing with his work but, almost imperceptibly, he had slackened his pace and for the first time had let himself wonder whether the silver cleaning had become too tiring for him to undertake alone. But that would be a humiliating defeat. Resolutely pulling the last candelabrum towards him, he took up a fresh polishing cloth and, easing his aching limbs in the chair, bent again to his task.

5

In the music room the gentlemen did not keep them waiting long and the atmosphere lightened as the company settled themselves comfortably on the sofa and chairs. The pianoforte was opened by Darcy and the candles on the instrument were lit. As soon as they had seated themselves, Darcy turned to Georgiana and, almost formally as if she were a guest, said that it would be a pleasure for them all if she would play and sing. She got up with a glance at Henry Alveston and he followed her to the instrument. Turning to the party she said, “As we have a tenor with us, I thought it would be pleasant to have some duets.”

“Yes!” cried Bingley enthusiastically. “A very good idea. Let us hear you both. Jane and I were trying last week to sing duets together, were we not, my love? But I won’t suggest that we repeat the experiment tonight. I was a disaster, was I not, Jane?”

His wife laughed. “No, you did very well. But I’m afraid I have neglected practising since Charles Edward was born. We will not inflict our musical efforts on our friends while we have in Miss Georgiana a more talented musician than you or I can ever hope to be.”

Elizabeth tried to give herself over to the music but her eyes and her thoughts were with the couple at the piano. After the first two songs a third was entreated and there was a pause as Georgiana picked up a new score and showed it to Alveston. He turned the pages and seemed to be pointing to passages which he thought might be difficult, or perhaps where he was uncertain how to pronounce the Italian. She looked up at him, and then played a few bars with her right hand and he smiled his acquiescence. Both of them seemed unaware of the waiting audience. It was a moment of intimacy which enclosed them in their private world, yet reached out to a moment when self was forgotten in their common love of music. Watching the candlelight on the two rapt faces, their smiles as the problem was solved and Georgiana settled herself to play, Elizabeth felt that this was no fleeting attraction based on physical proximity, not even in a shared love of music. Surely they were in love, or perhaps on the verge of love, that enchanting period of mutual discovery, expectation and hope.

It was an enchantment she had never known. It still surprised her that between Darcy’s first insulting proposal and his second successful and penitent request for her love, they had only been together in private for less than half an hour: the time when she and the Gardiners were visiting Pemberley and he unexpectedly returned and they walked together in the gardens, and the following day when he rode over to the Lambton inn where she was staying to discover her in tears, holding Jane’s letter with news of Lydia’s elopement. He had quickly left within minutes and she had thought never to see him again. If this were fiction, could even the most brilliant novelist contrive to make credible so short a period in which pride had been subdued and prejudice overcome? And later, when Darcy and Bingley returned to Netherfield and Darcy was her accepted lover, the courtship, so far from being a period of joy, had been one of the most anxious and embarrassing of her life as she sought to divert his attention from her mother’s loud and exuberant congratulations which had almost gone as far as thanking him for his great condescension in applying for her daughter’s hand. Neither Jane nor Bingley had suffered in the same way. The good-natured and love-obsessed Bingley either did not notice or tolerated his future mother-in-law’s vulgarity. And would she herself have married Darcy had he been a penniless curate or a struggling attorney? It was difficult to envisage Mr Fitzwilliam Darcy of Pemberley as either, but honesty compelled an answer. Elizabeth knew that she was not formed for the sad contrivances of poverty.

The wind was still rising and the two voices were accompanied by the moaning and howling in the chimney and the fitful blazing of the fire, so that the tumult outside seemed nature’s descant to the beauty of the two blending voices and a fitting accompaniment to the turmoil in her own mind. She had never before been worried by a high wind and would relish the security and comfort of sitting indoors while it raged ineffectively through the Pemberley woodland. But now it seemed a malignant force, seeking every chimney, every cranny, to gain entrance. She was not imaginative and she tried to put the morbid imaginings from her, but there persisted an emotion which she had never known before. She thought, Here we sit at the beginning of a new century, citizens of the most civilised country in Europe, surrounded by the splendour of its craftsmanship, its art and the books which enshrine its literature, while outside there is another world which wealth and education and privilege can keep from us, a world in which men are as violent and destructive as is the animal world. Perhaps even the most fortunate of us will not be able to ignore it and keep it at bay for ever.

She tried to restore tranquillity in the blending of the two voices, but was glad when the music ended and it was time to pull on the bell-rope and order the tea.

The tea tray was brought in by Billings, one of the footmen. She knew that he was destined to leave Pemberley in the spring when, if all went well, he could hope to succeed the Bingleys’ butler when the old man at last retired. It was a rise in importance and status, made the more welcome to him as he had become engaged to Thomas Bidwell’s daughter Louisa the Easter before last and she would accompany him to Highmarten as chief parlourmaid. Elizabeth, in her first months at Pemberley, had been surprised at the family’s involvement in the life of their servants. On Darcy’s and her rare visits to London they stayed in their townhouse or with Bingley’s sister, Mrs Hurst, and her husband, who lived in some grandeur. In that world the servants lived lives so apart from the family that it was apparent how rarely Mrs Hurst even knew the names of those who served her. But although Mr and Mrs Darcy were carefully protected from domestic problems, there were events – marriages, betrothals, changes of job, illness or retirement – which rose above the ceaseless life of activity which ensured the smooth running of the house, and it was important both to Darcy and Elizabeth that these rites of passage, part of that still largely secret life on which their comfort so much depended, should be recognised and celebrated.

Now Billings put down the tea tray in front of Elizabeth with a kind of deliberate grace, as if to demonstrate to Jane how worthy he was of the honour in store. It was, thought Elizabeth, to be a comfortable situation both for him and his new wife. As her father had prophesied, the Bingleys were generous employers, easy-going, undemanding and particular only in the care of each other and their children.

Hardly had Billings left when Colonel Fitzwilliam got up from his seat and walked over to Elizabeth. “Will you forgive me, Mrs Darcy, if I now take my nightly exercise? I have it in mind to ride Talbot beside the river. I’m sorry to break up so happy a family meeting but I sleep ill without fresh air before bed.”

Elizabeth assured him that no excuses were necessary. He raised her hand briefly to his lips, a gesture that was unusual in him, and made for the door.

Henry Alveston was sitting with Georgiana on the sofa. Looking up, he said, “Moonlight on the river is magical, Colonel, although perhaps best seen in company. But you and Talbot will have a rough ride of it. I do not envy you battling against this wind.”

The colonel turned at the door and looked at him. His voice was cold. “Then we must be grateful that you are not required to accompany me.” With a farewell bow to the company he was gone.

There was a moment of silence in which the colonel’s parting words and the singularity of his night ride were in every mind, but in which embarrassment inhibited comment. Only Henry Alveston seemed unconcerned although, glancing at his face, Elizabeth had no doubt that the implied criticism had not been lost on him.

It was Bingley who broke the silence. “Some more music, if you please, Miss Georgiana, if you are not too tired. But please finish your tea first. We must not impose on your kindness. What about those Irish folksongs which you played when we dined here last summer? No need to sing, the music itself is enough, you must save your voice. I remember that we even had some dancing, did we not? But then the Gardiners were here, and Mr and Mrs Hurst, so we had five couples, and Mary was here to play for us.”

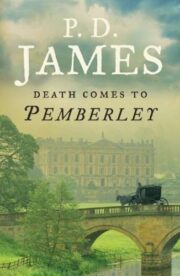

"Death Comes to Pemberley" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Death Comes to Pemberley". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Death Comes to Pemberley" друзьям в соцсетях.