George Pratt was now called to give evidence. In the dock he looked older than Darcy had remembered. His clothes were clean but not new and his hair had obviously been recently washed and now stood up stiffly in pale spikes round his face, giving him the petrified look of a clown. He took the oath slowly, his eyes fixed on the paper as if the language were foreign to him, then gazed at Cartwright with something of the entreaty of a delinquent child.

The prosecution counsel had obviously decided that kindness would here be the most effective tool. He said, “You have taken the oath, Mr Pratt, which means that you have sworn to tell the truth to this court both in reply to my questions and in anything you may say. I want you now to tell the court in your own words what happened on the night of Friday 14th October.”

“I was to take the two gentlemen, Mr Wickham and Captain Denny, and Mrs Wickham to Pemberley in Mr Piggott’s chaise and then leave the lady at the house and go on to take the gentlemen to the King’s Arms at Lambton. But Mr Wickham and the captain never got to Pemberley, sir.”

“Yes, we know that. How were you to get to Pemberley? By which gate to the property?”

“By the north-west gate, sir, and then through the woodland path.”

“And what happened? Was there any difficulty in getting through the gate?”

“No sir. Jimmy Morgan came to open it. He said no one was to pass through but he knew me and when I said I was to take Mrs Wickham to the ball he let us through. We was about half a mile or so down the path when one of the gentlemen – I think it was Captain Denny – knocked for me to stop, so I did. He got out of the chaise and made for the woodland. He shouted out that he wasn’t going to have any more of it and that Mr Wickham was on his own.”

“Were those his exact words?”

Pratt paused. “I can’t be sure, sir. He may have said, “You are on your own now, Wickham. I’ll have no more of it.” ”

“What happened next?”

“Mr Wickham got out of the chaise after him and called out that he was a fool and was to come back, but he didn’t. So Mr Wickham followed him into the woodland. The lady got out of the chaise calling out for him to come back and not leave her, but he took no notice. When he disappeared into the woodland she got back into the chaise and began crying something pitiful. So there we stood, sir.”

“You didn’t think yourself of going into the woods?”

“No sir. I couldn’t leave Mrs Wickham, nor the horses, so I stayed. But after a time there were shots and Mrs Wickham began screaming and said to me that we would all be killed and that I was to drive to Pemberley as fast as I could.”

“Were the shots close?”

“I couldn’t say, sir. But they was close enough to be heard plain.”

“And how many did you hear?”

“It could have been three or four. I can’t be certain, sir.”

“So what happened then?”

“I whipped the horses into a gallop and we made our way to Pemberley, the lady screaming all the while. When we pulled up at the door she almost fell out of the chaise. Mr Darcy and some of the company were at the door. I can’t rightly remember who but I think there was two gentlemen and Mr Darcy, and two ladies. The ladies helped Mrs Wickham into the house and Mr Darcy said I was to stay with the horses as he would want me to take him and some of the gentlemen back to the place where Captain Denny and Mr Wickham ran into the woods. So I waited, sir. And then the gentleman I now know is Colonel Fitzwilliam rode up the main drive very fast and joined the party. When someone had fetched a stretcher and some blankets and lanterns, the three gentlemen – Mr Darcy, the colonel and another man I didn’t know – got into the coach and we went back into the woodland. Then the gentlemen got out and walked in front until we came to the path to Woodland Cottage and the colonel went to see that the family was safe and to tell them to lock their door. Then the three gentlemen walked on further until I saw where I thought Captain Denny and Mr Wickham had disappeared. Then Mr Darcy told me to wait there and they went into the wood.”

“That must have been an anxious time for you, Pratt.”

“It was, sir. I was sore afraid having no one with me and no weapon, and the wait seemed very long, sir. But then I heard them coming. They brought Captain Denny’s body on a stretcher and Mr Wickham, who was unsteady on his feet, was helped into the chaise by the third gentleman. I turned the horses and we went slowly back to Pemberley with the colonel and Mr Darcy walking behind carrying the stretcher and the third gentleman in the chaise with Mr Wickham. After that it’s a muddle in my mind, sir. I know that the stretcher was carried away and Mr Wickham, who was shouting very loud and hardly standing on his feet, was taken into the house and I was asked to wait. At last the colonel came out and told me I should take the chaise on to the King’s Head and tell them that the gentlemen wouldn’t be coming but to get away quick before they could ask any questions, and when I got back to the Green Man I was to say nothing to anyone about what happened otherwise I would be in trouble with the police. He said they would be coming to talk to me next day. I was worried in case Mr Piggott asked me questions when I got back, but he and Mrs Piggott had gone to bed. By then the wind had dropped and there was a driving rain. Mr Piggott opened his bedroom window and called out if everything was all right and if the lady had been left at Pemberley. I said that she had and he told me to see to the horses and get to bed. I was dead tired, sir, and next morning was asleep when the police arrived just after seven o’clock. I told them what had happened, same as I’m now telling you, sir, as far as I can remember and with nothing held back.”

Cartwright said, “Thank you, Mr Pratt. That has been very clear.”

Mr Mickledore got to his feet immediately. He said, “I have one or two questions to put to you, Mr Pratt. When you were called by Mr Piggott to drive the party to Pemberley, was that the first time you had seen the two gentlemen together?”

“It was, sir.”

“And how did their relationship appear to you?”

“Captain Denny was very quiet and Mr Wickham had obviously taken drink, but there was no quarrel or argumenting.”

“Was there reluctance on the part of Captain Denny to enter the chaise?”

“There was none, sir. He got in happy enough.”

“Did you hear any talk between them on the journey before the chaise was stopped?”

“No sir. It would not have been easy with the wind and the rough ground unless they had been shouting really loud.”

“And there was no shouting?”

“No sir, not that I could hear.”

“So the party, as far as you know, set off on good terms with each other and you had no reason to expect any problems?”

“No sir, I had not.”

“I understand that at the inquest you told the jury of the trouble you had in controlling the horses when they were in the woodland. It must have been a difficult journey for them.”

“Oh it were, sir. As soon as they entered the woodland they were right nervy, neighing and stamping.”

“They must have been difficult for you to control.”

“They was, sir, proper difficult. There’s no horse likes going into the woodland in a full moon – no human neither.”

“Can you then be absolutely certain of the words Captain Denny spoke when he left the chaise?”

“Well sir, I did hear him say that he wouldn’t go along with Mr Wickham any more and that Mr Wickham was now on his own, or something like that.”

“Something like that. Thank you Mr Pratt, that is all I have to ask.”

Pratt was released, considerably happier than when he had entered the dock. Alveston whispered to Darcy, “No problem there. Mickledore has been able to cast doubt on Pratt’s evidence. And now, Mr Darcy, it will be either you or the colonel.”

7

When his name was called, Darcy responded with a physical shock of surprise although he had known that his turn could not be long in coming. He made his way across the courtroom between what seemed rows of hostile eyes and tried to govern his mind. It was important that he keep both his composure and his temper. He was resolute that he would not meet the gaze of Wickham, Mrs Younge or the jury member who, every time his own eyes scoured the jury box, gazed at him with an unfriendly intensity. He would keep his own eyes on the prosecuting counsel when answering questions, with occasional glances either at the jury or the judge who sat immobile as a Buddha, his plump little hands folded on the desk, his eyes half-closed.

The first part of the interrogation was straightforward. In answer to questions he described the evening of the dinner party, who was present, the departure of Colonel Fitzwilliam and Miss Darcy, the arrival of the chaise with a distraught Mrs Wickham, and finally the decision to take the chaise back to the woodland path to discover what had happened and whether Mr Wickham and Captain Denny were in need of any assistance.

Simon Cartwright said, “You were anticipating danger, perhaps tragedy?”

“By no means, sir. I had hoped, even expected, that the worst that had befallen the gentlemen would be that one had met with some minor but disabling accident in the woodland and that we should meet both Mr Wickham and Captain Denny making their slow way to Pemberley or back to the inn, one helping the other. It was the report by Mrs Wickham and subsequently confirmed by Pratt that there had been shooting which convinced me that it would be prudent to mount a rescue expedition. Colonel Fitzwilliam had returned in time to be part of the expedition and was armed.”

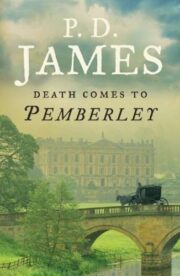

"Death Comes to Pemberley" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Death Comes to Pemberley". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Death Comes to Pemberley" друзьям в соцсетях.