His loss was felt by the whole household, and Mrs Reynolds was overheard saying to Stoughton, “It is strange, Mr Stoughton, that we should miss Mr Bennet so much now that he has left when we seldom set eyes on him when he was here.”

Darcy and Elizabeth both found solace in work, and there was much to be done. Darcy had in hand some plans already formed for the repair of certain cottages on the estate, and was busier than he had ever been engaged in parish matters. The war with France, declared the previous May, was already producing unrest and poverty; the cost of bread had risen and the harvest was poor. Darcy was much engaged in the relief of his tenants and there was a regular stream of children calling at the kitchen to collect large cans of nourishing soup, thick and meaty as a stew. There were few dinner parties and those only for close friends, but the Bingleys came regularly to give encouragement and help, and there were frequent letters from Mr and Mrs Gardiner.

After the inquest Wickham had been transferred to the new county prison at Derby where Mr Bingley continued to visit him and reported that he generally found him in good spirits. In the week before Christmas they finally heard that the application to transfer the trial to London had been agreed and that it would take place at the Old Bailey. Elizabeth was determined that she would be with her husband on the day of the trial, although there was no question of her being present in the courtroom. Mrs Gardiner wrote with a warm invitation that Darcy and Elizabeth should spend their time in London at Gracechurch Street, and this was gratefully accepted. Before the New Year George Wickham was transferred to Coldbath Prison in London and Mr Gardiner took over the duty of making regular visits and of paying the sums from Darcy which ensured Wickham’s comfort and his status with the turnkeys and his fellow prisoners. Mr Gardiner reported that Wickham remained optimistic and that one of the chaplains at the prison, the Reverend Samuel Cornbinder, was seeing him regularly. Mr Cornbinder was known for his skill at chess, a game which he had taught Wickham and which was now occupying much of the prisoner’s time. Mr Gardiner thought that the reverend gentleman was welcomed more as a chess opponent than as an admonisher to repentance but Wickham seemed genuinely to like him and chess, at which he was becoming interested to the point of obsession, was an effective antidote to his occasional outbursts of anger and despair.

Christmas came and the annual children’s party, to which all the children on the estate were invited, was held as usual. Both Darcy and Elizabeth felt that the young should not be deprived of this yearly treat, especially in such difficult times. Gifts had to be chosen and delivered to all the tenants as well as the indoor and outdoor staff, a task which kept both Elizabeth and Mrs Reynolds occupied, while Elizabeth tried to keep her mind busy by a planned programme of reading, and by improving her performance at the pianoforte with Georgiana’s help. With fewer social obligations Elizabeth had time to spend with her children or in visiting the poor, the elderly and the infirm, and both Darcy and Elizabeth were to find that, with days so filled with activity, even the most persistent nightmares could occasionally be kept at bay.

There was some good news. Louisa was much happier since Georgie had gone back to his mother and Mrs Bidwell was finding life easier now that the child’s crying was not causing Will distress. After Christmas the weeks suddenly seem to pass far more quickly as the date set for the trial rapidly approached.

Book Five

The Trial

1

The trial was scheduled to take place on Thursday 22nd March at eleven o’clock at the Old Bailey. Alveston would be at his rooms near the Middle Temple and had suggested that he wait upon the Gardiners at Gracechurch Street the day before, together with Jeremiah Mickledore, Wickham’s defence counsel, to explain the next day’s procedure and to advise Darcy on the evidence he would give. Elizabeth was anxious to take two days on the road so they proposed to stop at Banbury overnight, arriving in the early afternoon of Wednesday 21st March. Usually when the Darcys left Pemberley a group of the more senior staff would be at the door to wave goodbye and express their good wishes, but this departure was very different and only Stoughton and Mrs Reynolds were there, their faces grave, to wish them a safe journey and assure the Darcys that life at Pemberley would continue as it should while they were away.

To open the Darcy townhouse entailed considerable domestic disruption, and when visiting London for a short period for shopping, to view a new play or exhibition, or because Darcy had business with his lawyer or tailor, they would stay with the Hursts when Miss Bingley would join the party. Mrs Hurst preferred any visitor to none and took pride in exhibiting the splendour of her house and the number of her carriages and servants, while Miss Bingley could artfully drop the names of her distinguished friends and pass on the current gossip about scandals in high places. Elizabeth would indulge the amusement she had always taken in the pretensions and absurdities of her neighbours, provided no compassion was called for, while Darcy took the view that if family amity required him to meet people with whom he had little in common, it were best done at their expense not his. But on this occasion no invitation from the Hursts or Miss Bingley had been received. There are some dramatic events, some notoriety, from which it is prudent to distance oneself and they did not expect to see either the Hursts or Miss Bingley during the trial. But the invitation from the Gardiners had been immediate and warm. Here in that comfortable, unostentatious family house they would find the reassurance and security of familiarity, quietly speaking voices that would make no demands, require no explanations, and a peace which might prepare them for the ordeal ahead.

But when they reached the centre of London and the trees and green expanse of Hyde Park were behind them, Darcy felt that he was entering an alien state, breathing a stale and sour-smelling air, and surrounded by a large and menacing population. Never before had he felt so much a stranger in London. It was hard to believe that the country was at war; everyone seemed in a hurry, all walked as if preoccupied with their own concerns, but from time to time he saw envious or admiring glances cast at the Darcy coach. Neither he nor Elizabeth were disposed to comment as they passed into the wider and better-known streets where the coachman edged his careful way between the bright and gaudy shopfronts lit by flares, and the chaises, carts, wagons and private coaches which made the roads almost impassable. But at last they turned into Gracechurch Street and even as they approached the Gardiners’ house the door was opened and Mr and Mrs Gardiner ran out to welcome them and to direct the coachman to the stables at the rear. Minutes later the baggage was unloaded and Elizabeth and Darcy walked into the peace and security which would be their refuge until the trial was over.

2

Alveston and Jeremiah Mickledore came after dinner to give Darcy brief instructions and advice, and, having expressed their hopes and best wishes, left in less than an hour. It was to be one of the worst nights of Darcy’s life. Mrs Gardiner, unfailingly hospitable, had ensured that there was everything in the bedroom necessary for Elizabeth’s and his comfort, not only the two longed-for beds but the table between them with the carafe of water, the books and the tin of biscuits. Gracechurch Street could not be completely quiet but the rumble and creaks of carriages and the occasional calling voices, a contrast to the total silence of Pemberley, would not normally have been enough to keep him awake. He tried to put the anxiety about tomorrow’s ordeal out of his mind, but it was too occupied with even more disturbing thoughts. It was as if an image of himself were standing by the bed regarding him with accusatory, almost contemptuous eyes, rehearsing arguments and indictments which he had thought he had long disciplined into quiescence but which this unwanted vision had now brought forward with renewed force and reason. It was his own doing and no one else’s that had made Wickham part of his family with the right to call him brother. Tomorrow he would be compelled to give evidence which could help send his enemy to the gallows or set him free. Even if the verdict were “not guilty”, the trial would bring Wickham closer to Pemberley, and if he were convicted and hanged, Darcy himself would carry a weight of horror and guilt which he would bequeath to his sons and to future generations.

He could not regret his marriage; it would have been like regretting that he himself had ever been born. It had brought him happiness which he had never believed possible, a love of which the two handsome and healthy boys sleeping in the Pemberley nursery was a pledge and an assurance. But he had married in defiance of every principle which from childhood had ruled his life, every conviction of what was owed to the memory of his parents, to Pemberley and to the responsibility of class and wealth. However deep the attraction to Elizabeth he could have walked away, as he suspected Colonel Fitzwilliam had walked away. The price he had played in bribing Wickham to marry Lydia had been the price of Elizabeth.

He remembered the meeting with Mrs Younge. The rooming house was in a respectable part of Marylebone, the woman herself the personification of a reputable and caring landlady. He remembered their conversation. “I accept only young men from the most respectable families who have left home to take work in the capital and to begin their careers of independence. Their parents know that the boys will be well fed and cared for, and a judicious eye kept on their behaviour. I have had, for many years, a more than adequate income, and now that I have explained my situation we can do business. But first may I offer you some refreshment?”

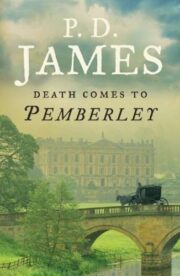

"Death Comes to Pemberley" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Death Comes to Pemberley". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Death Comes to Pemberley" друзьям в соцсетях.