Darcy gained the impression that Pratt’s story was already known to the jury, and probably to the whole of Lambton and Pemberley village and beyond, and his evidence was given with a back-ground of sympathetic groans and sighs, particularly when he dwelt on the distress of Betty and Millie. There were no questions.

Colonel the Viscount Hartlep was then called and the oath administered with impressive authority. The colonel briefly but firmly recounted his part in the events of the evening, including the finding of the body, evidence which was later repeated, also without emotion or embellishment, by Alveston, and lastly by Darcy. All three were asked by the coroner whether Wickham had spoken, and his damaging admission was repeated.

Before anyone else had a chance to speak, Makepeace asked the vital question. “Mr Wickham, you are resolutely maintaining your innocence of Captain Denny’s murder. Why then, when found kneeling over his body, did you say more than once that you killed him and that his death was your fault?”

The answer came without hesitation. “Because, sir, Captain Denny left the chaise out of disgust with my plan to leave Mrs Wickham at Pemberley uninvited and unexpected. I also felt that, had I not been drunk, I might have prevented him leaving the chaise and charging into the woodland.”

Clitheroe whispered to Darcy, “Totally unconvincing, the fool is overconfident. He will need to do better than this at the assizes if he is to save his neck. And how drunk was he?”

No questions were, however, asked, and it appeared that Makepeace was content to let the jury come to their opinion without his comments and was wary of encouraging the witnesses to speculate at length on what, precisely, Wickham had meant by his words. Headborough Brownrigg followed and had obvious pleasure in taking his time over his account of the police activity, including the search of the woodland. No information had been received of any strangers in the vicinity, the occupants of Pemberley House and of all the cottages on the estate had alibis and the investigation was still proceeding. Dr Belcher gave his evidence largely in medical terms, to which his audience listened with respect and the coroner with obvious irritation, before delivering his opinion in plain English that the cause of death was a heavy blow to the back of the head and that Captain Denny could not have survived such an injury for more than a few minutes, if that, although it was impossible to give an accurate estimate of the time of death. A slab of stone which could have been used by the assailant had been discovered and which, in his view, could in size and weight have produced such a wound if delivered by force, but there was no evidence to link this particular stone with the crime. Only one hand was raised before he left the witness box.

Makepeace said, “Well Frank Stirling, we usually hear from you. What is it you want to ask?”

“Just this, sir. We understand that Mrs Wickham was to be left at Pemberley House to attend the ball the next night, but not with her husband. I take it that Mr Wickham would not be received as a guest by his brother and Mrs Darcy.”

“And what is the relevance of Mrs Darcy’s guest list for Lady Anne’s ball to the death of Captain Denny, or indeed to the evidence just given by Dr Belcher?”

“Only this, sir, that if relations was so bad between Mr Darcy and Mr Wickham, and it might be that Mr Wickham was not a proper person to be received at Pemberley, then that would have some bearing on his character, as I see it. It is a powerful strange thing for a man to forbid his house to a brother unless it might be that the brother was a violent man or given to quarrelling.”

Makepeace appeared briefly to consider his words before replying that the relationship between Mr Darcy and Mr Wickham, whether or not it was the usual one between brothers, could have no relevance to the death of Captain Denny. It was Captain Denny not Mr Darcy who had been murdered. “Let us try to keep to the relevant facts. You should have raised the question when Mr Darcy was giving evidence if you thought it relevant. However, Mr Darcy can be recalled to the witness stand and asked whether Mr Wickham was in general a violent man.”

This was immediately done and in reply to Makepeace’s question, Darcy, after being reminded that he was still on oath, said that, as far as he knew, Mr Wickham had never had that reputation and that he personally had never seen him violent. They had not met for some years but at that time Mr Wickham had been generally known as a peaceable and socially affable man.

“I take it that satisfies you, Mr Stirling. A peaceable and affable man. Are there any further questions? No? Then I suggest that the jury now consider their verdict.”

After some conferring they decided to do this in private and, being dissuaded from entering their choice of venue, the bar, disappeared into the yard and stood for ten minutes at a distance in a whispering group. On their return they were formally asked for their verdict. Frank Stirling then stood up and read from a small notebook, obviously determined to deliver the words with the necessary accuracy and confidence. “We find, sir, that Captain Denny died from a blow to the back of the skull and that this fatal blow was delivered by George Wickham and, accordingly, Captain Denny was murdered by the said George Wickham.”

Makepeace said, “And that is the verdict of you all?”

“It is, sir.”

Makepeace took off his spectacles after glaring at the clock and replaced them in their case. He said, “After the necessary formalities Mr Wickham will be committed for trial at the next Derby assize. Thank you, gentlemen, you are dismissed.”

Darcy reflected that a process he had expected to be fraught with linguistic pitfalls and embarrassment had proved almost as much a matter of routine as the monthly parish meeting. There had been interest and commitment but no obvious excitement or moments of high drama, and he had to accept that Clitheroe was right, the outcome had been inevitable. Even if the jury had decided for murder by a person or persons unknown, Wickham would still be in custody as prime suspect and the police inquiries, centred on him, would have continued with almost certainly the same result.

Clitheroe’s servant now reappeared to take control of the wheelchair. Consulting his watch, Clitheroe said, “Three-quarters of an hour from start to finish. I imagine it went exactly as Makepeace planned, and the verdict could hardly be otherwise.”

Darcy said, “And the verdict at the trial will be the same?”

“By no means, Darcy, by no means. I could mount a very effective defence. I suggest you find him a good lawyer and if possible get the case transferred to London. Henry Alveston will be able to advise you on the appropriate procedure, my information is probably out of date. That young man is something of a radical, I hear, despite being heir to an ancient barony, but he is undoubtedly a clever and successful lawyer, although it is time he found himself a wife and settled on his estate. The peace and security of England depends on gentlemen living in their houses as good landlords and masters, considerate to their servants, charitable to the poor, and ready, as justices of the peace, to take a full part in promoting peace and order in their communities. If the aristocrats of France had lived thus, there would never have been a revolution. But this case is interesting and the result will depend on the answers to two questions: why did Captain Denny run into the woodland, and what did George Wickham mean when he said it was all his fault? I shall watch further developments with interest. Fiat justitia ruat caelum. I wish you good day.”

And with this the wicker bath chair was manoeuvred, again with some difficulty, through the door and out of sight.

7

For Darcy and Elizabeth the winter of 1803–4 stretched like a black slough through which they must struggle, knowing that spring could only bring a new ordeal, and perhaps an even greater horror, the memory of which would blight the rest of their lives. But somehow those months had to be lived through without letting their anguish and distress overshadow the life of Pemberley or destroy the peace and confidence of those who depended on them. Happily this anxiety was to prove largely unfounded. Only Stoughton, Mrs Reynolds and the Bidwells had known Wickham as a boy, and the younger servants had little interest in anything that happened outside Pemberley. Darcy had given orders that the trial should not be spoken of and the approach of Christmas was a greater source of interest and excitement than was the eventual fate of a man of whom the majority of the servants had never even heard.

Mr Bennet was a quiet and reassuring presence in the house, rather like a benign, familiar ghost. He spent some of the time when Darcy was able to be free in conversation with him in the library; Darcy, himself clever, valued high intelligence in others. From time to time Mr Bennet would visit his eldest daughter at Highmarten to ensure that the volumes in Bingley’s library were safe from the housemaids’ overzealous attention and to make a list of books to be acquired. He stayed at Pemberley, however, for only three weeks. A letter was received from Mrs Bennet complaining that she could hear stealthy footsteps outside the house every night and was suffering from continual palpitations and fluttering of the heart. Mr Bennet must come home at once to provide protection. Why was he concerning himself with other people’s murders when there was likely to be one at Longbourn if he did not immediately return?

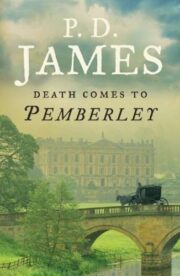

"Death Comes to Pemberley" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Death Comes to Pemberley". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Death Comes to Pemberley" друзьям в соцсетях.