“In good heart. The contrast between his present appearance and that in the day following the attack on Denny is remarkable, but then, of course, he was in liquor and deeply shocked. He has recovered both his courage and his looks. He is remarkably sanguine about the result of the inquest and Alveston thinks he has a right to be. The absence of any weapon certainly weighs in his favour.”

They both seated themselves. Darcy saw that Mr Bennet’s eyes were straying towards the Edinburgh Review but he resisted the temptation to resume reading. He said, “I wish Wickham would make up his mind how he wishes to be regarded by the world. At the time of his marriage he was an irresponsible but charming lieutenant in the militia, he made love to us all, simpering and smiling as if he had brought to his marriage three thousand a year and a desirable residence. Later, after taking his commission, he metamorphosed into a man of action and public hero, a change certainly for the better and one highly agreeable to Mrs Bennet. And now we are expected to see him as deep-dyed in villainy and at some risk, although I hope remote, of ending as a public spectacle. He has always sought notoriety, but hardly, I think, the final appearance now threatened. I cannot believe him guilty of murder. His misdemeanours, however inconvenient for his victims, have not, as far as I know, involved violence either to himself or others.”

Darcy said, “We cannot look into another’s mind, but I believe him to be innocent and I shall ensure that he has the best legal advice and representation.”

“That is generous of you, and I suspect – although I have no firm knowledge – that it is not the first act of generosity which my family owes to you.” Without waiting for a reply, he said quickly, “I understand from Colonel Fitzwilliam that Elizabeth and Miss Darcy are engaged in some charitable enterprise, taking a basket of necessities to an afflicted family. When are they expected back?”

Darcy took out his watch. “They should be on their way now. If you are inclined for exercise, sir, would you care to join me and we can walk towards the woodland to meet them.”

It was obvious that Mr Bennet, although known to be sedentary, was willing to relinquish the Review and the comfort of the library fire for the pleasure of surprising his daughter. It was then that Stoughton appeared, apologising that he had not been at the door when his master returned and quick to fetch the gentlemen’s hats and greatcoats. Darcy was as eager as his companion to see the landaulet come into sight. He would have prevented the excursion had he thought it in any way dangerous, and he knew Alveston to be both trustworthy and resourceful, but since Denny’s murder he had been consumed with an unfocused and perhaps irrational anxiety whenever his wife was not within his view, and it was with relief that he saw the landaulet slow and then come to a stop within fifty yards of Pemberley. He had not realised how profoundly he was glad to see Mr Bennet until he saw Elizabeth get hurriedly out and run towards her father and heard her delighted “Oh Father, how good to see you!” as he enfolded her in his arms.

6

The inquest was held at the King’s Arms in a large room built at the back of the inn some eight years previously to provide a venue for local functions, including the occasional dance dignified always as a ball. Initial enthusiasm and local pride had ensured its early success but in these difficult times of war and want there was neither money nor inclination for frivolity and the room, now used mostly for official meetings, was seldom filled to anything like capacity and had the slightly depressing and neglected atmosphere of any place once intended for communal activity. The innkeeper, Thomas Simpkins, and his wife Mary had made the usual preparations for an event which they knew would undoubtedly attract a large audience and subsequently profit for the bar. To the right of the door was a platform large enough to accommodate a small orchestra for dancing, and on this had been placed an impressive wooden armchair taken from the private bar, and four smaller chairs, two on each side, for justices of the peace or other local worthies who chose to attend. All other chairs available in the inn had been brought into use and the motley collection suggested that neighbours had also made their contribution. Latecomers were expected to stand.

Darcy was aware that the coroner took an elevated view of his status and responsibilities and would have been happy to see the owner of Pemberley arrive in state in his coach. Darcy would himself have preferred to have ridden, as the colonel and Alveston proposed to do, but compromised by using the chaise. When he entered the room he saw that it was already well filled and there was the usual anticipatory chat which to Darcy sounded more subdued than expectant. It fell silent on his appearance and there was much touching of forelocks and murmurings of greeting. No one, not even among his tenants, came forward to invite his notice as he knew they would normally have done, but he judged that this was less an affront than a feeling on their part that it was his privilege to make the first move.

He looked round to see if there was an empty seat somewhere at the back, preferably with others that he could reserve for the colonel and Alveston, but at that moment there was a commotion at the door and a large wicker bath chair with a small wheel at the front and two much larger at the back, was being manoeuvred with difficulty through the door. In it Dr Josiah Clitheroe sat in some state, his right leg supported by an obtruding plank, the foot turbaned in a bandage of white linen, intricately wound. Those sitting at the front quickly disappeared and Dr Clitheroe was pushed through, not without difficulty since the small wheel, snaking wildly, proved recalcitrant. The chairs each side of him were immediately vacated and on one he placed his tall hat and beckoned to Darcy to occupy the second. The circle of chairs round them was now empty and there was at least some chance of a private conversation.

Dr Clitheroe said, “I don’t think this will take all day. Jonah Makepeace will keep everything under control. It is a difficult business for you, Darcy, and of course for Mrs Darcy. I trust she is well.”

“She is, sir, I am happy to say.”

“Obviously you can take no part in the investigation of this crime but no doubt Hardcastle has kept you informed of developments.”

Darcy said, “He has said as much as he thinks it prudent to reveal. His own position is one of some difficulty.”

“Well he need not be too cautious. He will in duty bound keep the High Constable informed and will also consult me as necessary, although I am doubtful that I can be of much assistance. He, Headborough Brownrigg and Petty Constable Mason seem to have things under control. I understand they have spoken to everyone at Pemberley and are satisfied that you all have alibis; hardly surprising – on the evening before Lady Anne’s ball there are better things to do than trudge through the Pemberley woodland bent on murder. Lord Hartlep too, I am informed, has an alibi, so at least he and you can be relieved of that anxiety. As he is not yet a peer it would be unnecessary, in the event of his being charged, for him to be tried in the House of Lords, a colourful but expensive procedure. You will also be relieved to know that Hardcastle has traced Captain Denny’s next of kin through the colonel of his regiment. It appears that he has only one living relative, an elderly aunt residing in Kensington whom he rarely visits but who supplies some regular financial support. She is nearly ninety and too old and frail to take a personal interest in events but has asked that Denny’s body, now released by the coroner, should be sent to Kensington for burial.”

Darcy said, “If Denny had died in the woodland by a known hand or by accident, it would be right for Mrs Darcy or myself to send her a letter of condolence, but in the circumstances that might be ill advised and even unwelcome. It is strange how even the most terrible and bizarre events have social implications and it is good of you to pass on this information, which will, I know, be a relief to Mrs Darcy. What about the tenants on the estate? I hardly like to question Hardcastle directly; have they all been cleared?”

“Yes, I gather so. The majority were at home and those who can never resist venturing forth even on a stormy night to fortify themselves at the local inn have produced a superfluity of witnesses, some of whom were sober when questioned and can be considered reliable. Apparently no one has seen or heard of any stranger in the neighbourhood. You know, of course, that when Hardcastle visited Pemberley two silly young girls employed as housemaids came forward with the story of seeing the ghost of Mrs Reilly wandering in the woodland. Appropriately, she chooses to manifest herself on the night of the full moon.”

Darcy said, “That is an old superstition. Apparently, as we later heard, the girls were there as a result of a dare and Hardcastle did not take it seriously. I thought at the time that they were telling the truth and that there could have been a woman in the woodland that night.”

Clitheroe said, “Headborough Brownrigg has spoken to them in Mrs Reynolds’s presence. They were remarkably persistent in affirming that they had seen a dark woman in the woods two days before the murder, and that she made a threatening gesture before disappearing among the trees. They are adamant that this apparition was neither of the two women at Woodland Cottage, although it is difficult to see how they can assert this so confidently since the woman was in black and faded away as soon as one of the girls screamed. If there was a woman in the woodland it is hardly of much importance. This was not a woman’s crime.”

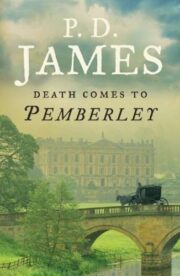

"Death Comes to Pemberley" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Death Comes to Pemberley". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Death Comes to Pemberley" друзьям в соцсетях.